In a Nutshell

- Cover crops are gaining new attention for their ability to reduce weed pressure in soybeans. Specifically, when seeding soybeans directly into a thick cover crop.

- Farmer-cooperators Jack Boyer and Scott Shriver investigated the effect of row-width on soybean yields when rolling a cereal rye cover crop. Boyer rolled select strips after terminating with an herbicide; Shriver used a roller-crimper to terminate his cover crop.

Key Findings

- The narrowest soybean row-width at both farms (10-in. at Boyer’s; 7.5-in. at Shriver’s) resulted in greatest yields.

- Boyer saw the greatest return on investment where he drilled soybeans in 10-in. rows and did not roll the cover crop after chemical termination. The drill itself appeared to lay down much of the cover crop residue.

Soybeans at Jack Boyer’s on July 22. Photos on top depict soybeans in 30-in. rows and photos below depict soybeans in 10-in. rows. Photos on the left depict where the cover crop was not rolled after chemical termination. Photos on the right depict where cover crops were rolled after chemical termination.

Background

In recent years, Practical Farmers of Iowa have realized the capacity of cover crops to reduce weed pressure in soybeans. In the past two years, farmer-researchers have documented reduced herbicide use when planting soybeans into a tall, thick cereal rye cover crop that they chemically terminated near the time of soybean planting (Gailans et al., 2016). The roller-crimper is a large, metal cylinder with “chevron” pattern blades that presents farmers the opportunity to mechanically terminate cover crops without chemicals or tillage. Research in central Illinois has found that roll-crimping a cereal rye cover crop ahead of no-till soybeans can result in similar weed control and yield to where the cover crop was chemically terminated (Davis, 2010). Weed control with this method is reliant on high levels of cover crop biomass production prior to rolling and biomass persistence through the soybean growing season (Smith et al., 2011). Successful termination of a cover crop by rolling is reliant upon the cover crop being at the anthesis (flowering) stage at the time of rolling (Mirsky et al., 2009). For cereal rye, this flowering stage is likely to occur in late May in Iowa. PFI farmers have recently wondered if other rolling equipment (cultimulchers, stalk choppers, etc.) they may have on the farm can accomplish successful cover crop termination and weed control on par with the actual roller-crimper.

The objective of this study was to assess the effectiveness of rolling a cereal rye cover crop ahead of soybeans planted in various row-widths (7.5–30-in.). Two farms participated in the study—Jack Boyer (conventional) and Scott Shriver (organic). Boyer used a land roller and Shriver used an actual roller-crimper to roll the cover crop. The farmers were particularly interested in managing weeds in the soybeans with the rolled cover crop mulch. “I was particularly interested in learning if rolling the cover crop would provide better weed control,” Boyer said.

Methods

Jack Boyer rolling the chemically terminated cover

crop with a RiteWay roller on June 6. Soybeans were seeded on May 16.

This trial was conducted by Jack Boyer near Reinbeck in Tama County and Scott Shriver (certified organic) near Jefferson in Greene County. At both farms, treatments were replicated four times in side-by-side strips running the length of the field.

Treatments at Boyer’s:

- Soybean row-width: 10-in. vs. 30-in. Seeded 5 days prior to cover crop termination.

- Cover crop termination: Spray, then roll cover into flat mulch vs. Spray, then let cover stand.

Treatments at Shriver’s:

- Soybean row-width: 7.5-in. vs. 15-in. vs. 30-in. Seeded 5 days prior to roll-crimping cover crop.

Cereal rye cover crop was drilled on Oct. 1, 2016 at a rate of 50 lb/ac at Boyer’s and on Oct. 11 at a rate of 160 lb/ac at Shriver’s.

Both farmers seeded soybeans prior to terminating the cover crop. Soybeans were seeded at a population of 150,000 seeds/ac on May 16, 2017 at Boyer’s for both row-widths. Boyer used a no-till drill for the 10-in. treatment and a planter for the 30-in. treatment. At Shriver’s, soybeans were seeded at a population of 220,000 seeds/ac for the 7.5-in. treatment, 200,000 seeds/ac for the 15-in. treatment and 185,000 seeds/ac for the 30-in. treatment on June 1. Shriver used a planter with 30-in. spacings to seed the soybeans; he used multiple passes (with auto-steer) to accomplish the 15- and 7.5-in. row-widths.

Aboveground biomass of the cereal rye cover crop was sampled from each strip just prior to termination at each farm. Samples were collected by clipping all shoot and leaf material from randomly placed quadrats (1 ft x 1 ft) within each strip. Samples were air-dried and weighed.

Boyer chemically terminated the cereal rye cover crop on May 24 with Roundup Powermax (44 oz/ac) and applied Outlook on May 31. He then rolled the cover crop in designated strips with a RiteWay roller on June 6 after the soybeans had grown past the first trifoliate stage. Rolling the cover crop at Shriver’s took place on June 6 with a roller-crimper made by Tru-Flex Rollers.

Soybean stand counts were conducted on Aug. 8 at Shriver’s.

Soybeans were harvested from each individual strip on Oct. 21 at Boyer’s and Oct. 27 at Shriver’s and corrected to 13% moisture.

Data were analyzed by farm using JMP Pro 12 statistical software (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC). Means separations among treatments are reported using Tukey’s least significant difference (LSD). Regression analysis was used to determine the effect of plant population on yield at Shriver’s. Statistical significance is reported at the P ≤ 0.05 level.

Results and Discussion

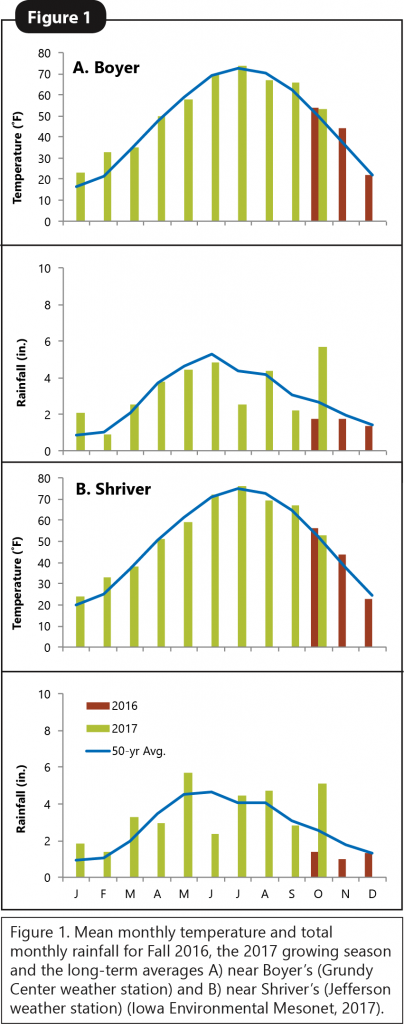

Mean monthly temperature and total monthly rainfall for 2017 near Boyer’s and Shriver’s farms compared to the 50-yr averages is presented in Figure 1 (Iowa Environmental Mesonet, 2017). October and November 2016 were drier than average at both farms, but Spring 2017 saw either normal (Boyer) or above-normal (Shriver) rainfall and normal temperatures. These made for very favorable conditions for the cover crops to emerge from winter dormancy. During the soybean growing season, rainfall was half the average in June at Shriver’s and July at Boyer’s. Temperatures at both farms during the 2017 growing season were near normal.

Mean monthly temperature and total monthly rainfall for 2017 near Boyer’s and Shriver’s farms compared to the 50-yr averages is presented in Figure 1 (Iowa Environmental Mesonet, 2017). October and November 2016 were drier than average at both farms, but Spring 2017 saw either normal (Boyer) or above-normal (Shriver) rainfall and normal temperatures. These made for very favorable conditions for the cover crops to emerge from winter dormancy. During the soybean growing season, rainfall was half the average in June at Shriver’s and July at Boyer’s. Temperatures at both farms during the 2017 growing season were near normal.

Cover crop biomass prior to termination

Both farmers collected cereal rye cover crop aboveground biomass samples prior to termination in Spring 2017. Boyer sampled on May 20; the cover crop biomass was 11,780 lb/ac of dry matter. Shriver sampled on June 1; the cover crop biomass was 15,165 lb/ac. Smith et al. (2011) reported that over 8,000 lb/ac of cereal rye cover crop biomass was necessary for sufficient weed control through the soybean growing season in research conducted in North Carolina.

Soybeans—Boyer

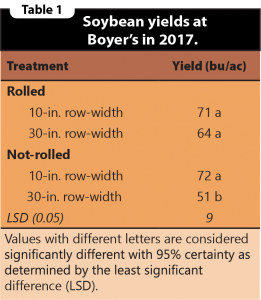

Soybean yields at the Boyer farm are presented in Table 1. Where the cover crop was rolled, there was no difference in soybean yield between the 10- and 30-in. row-widths. Where the cover crops were not rolled, soybeans in the 30-in. row-width yielded significantly less than the soybeans in the other three treatments. Yields for all treatments at Boyer’s were either near or above 55 bu/ac, the 5-yr average for Tama County (USDA-NASS, 2017). It is important to note that in all four treatments, there were no additional herbicide applications after the chemical termination of the  cover crop in late May. By mid-July Boyer observed the weed control by the cover crop mulch to be excellent. This aligns with findings by Davis (2010) in central Illinois who reported less weed biomass in soybeans planted into a recently terminated cereal rye cover crop that had produced 5,300–6,300 lb/ac of aboveground biomass than soybeans following no cover crop. Boyer planted into 11,780 lb/ac of cover crop dry matter.

cover crop in late May. By mid-July Boyer observed the weed control by the cover crop mulch to be excellent. This aligns with findings by Davis (2010) in central Illinois who reported less weed biomass in soybeans planted into a recently terminated cereal rye cover crop that had produced 5,300–6,300 lb/ac of aboveground biomass than soybeans following no cover crop. Boyer planted into 11,780 lb/ac of cover crop dry matter.

Boyer did experience some difficulty while harvesting the soybeans in 30-in. rows where the cover crop was not rolled. “The rye was standing between the rows and had a tendency to bunch up and create a blockage [while combining],” he said. “In the 10-in. rows the drill apparently laid the rye down enough that it was not as much of a problem.” Boyer also estimated that the final stand in the not-rolled, 30-in. row-width treatment was approximately 30% lower than the other treatments. “Emergence was equal at the start; however, some disease must have attacked the not-rolled strips. There just were not as many beans there [at harvest].”

Soybeans in 30-in. rows at harvest at Boyer’s. At left, cover crop was not rolled after chemical termination. At right, cover crop was rolled after chemical termination.

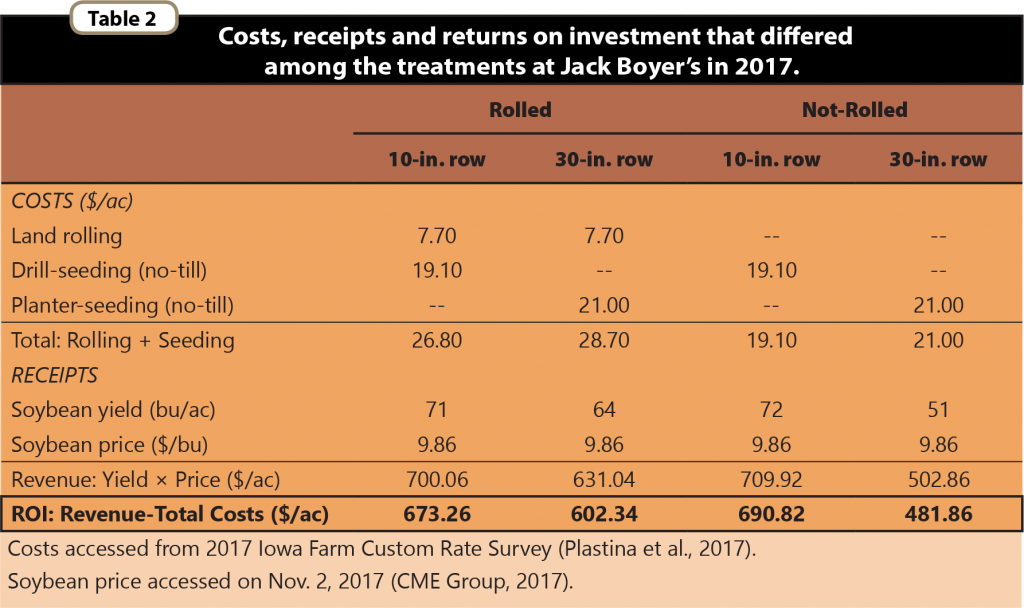

Table 2 provides a summary of costs, receipts and returns on investment that differed among the treatments at Boyer’s. Costs associated with cover crop seeding, chemical termination and soybean harvest were equivalent across treatments and are thus not considered when calculating the return on investment for each of the four treatments. Return on investment was greatest when the cover crop was not rolled and the soybeans were drilled in 10-in. rows. This treatment incurred the least costs and greatest soybean yield. Rolling the cover crop into a flat mulch where the soybeans were planted in 30-in. rows was a sound investment as both yields and returns were vastly improved compared to where the cover crop was not rolled with the 30-in. row-width.

Soybeans—Shriver

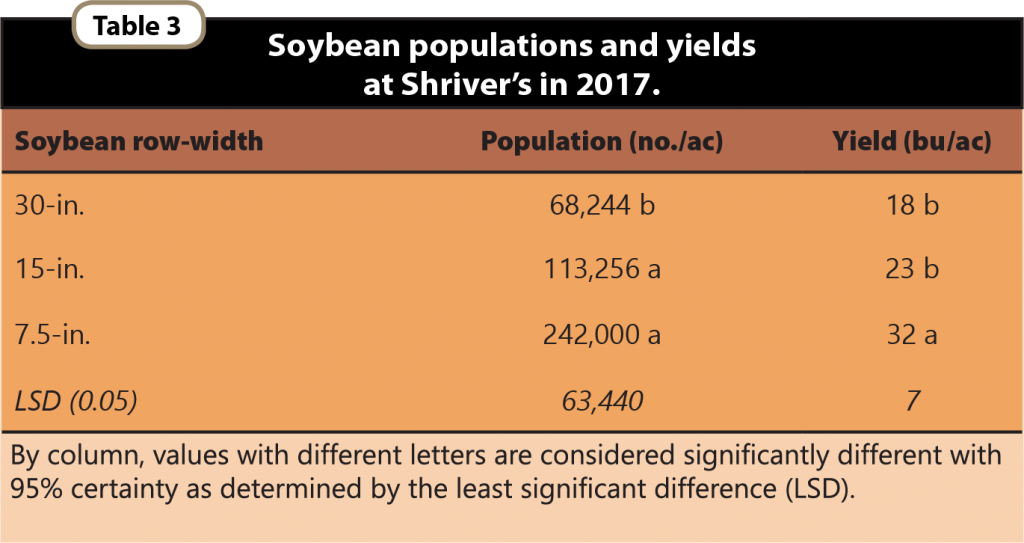

Shriver conducted stand counts in each strip on Aug. 8. Plant populations were least in the 30-in. row-width and were similar between the 15- and 7.5-in. row-width treatments (Table 3). Shriver’s target planting populations were 185,000 seeds/ac for the 30-in. row-width, 200,000 seeds/ac for the 15-in. row-width and 220,000 seeds/ac for the 7.5-in. row-width. Only the soybeans in the 7.5-in. row-width were near the target planting population and actually exceeded the target (242,000 plants/ac).

Soybean yields at Shriver’s were also affected by soybean row-width (Table 3). Greatest yields were recorded with the 7.5-in. row-width while yields were similar between the 15- and 30-in. row-widths. Regression analysis showed a very strong effect of plant population on yield (P = 0.0034). It is quite evident that the soybeans in the 30-in. row-width suffered from low yields due to a plant population that was 40% of the target planting rate. Yields from all treatments at Shriver’s were below the 5-yr Greene County average of 49 bu/ac (USDA, 2017). Shriver noted that the drier-than-normal month of June (Figure 1B) combined with the amount of cover crop growth probably stunted soybean growth early and reduced yields. “I had an overall problem in the field of getting the soybeans to grow and I think it was mostly due to poor planting (open seed trench, planter penetration, seed to soil contact, etc.) heightened by lack of rainfall,” he said. Shriver accomplished the different row-widths by offsetting his planter with auto steering and making multiple passes over the same area to get the 15- and 7.5-in. row-widths. “I believe these multiple passes helped the previous passes with their poor planting issues. Therefore, I do not believe we can conclude that the yield differences are solely from the different row spacings.” Proper planter settings have been cited by numerous farmers as essential to success when using cover crops.

Soybeans in 7.5-in. rows (left), 15-in. rows (middle) and 30-in. rows at Shriver’s on Aug. 8. Soybeans were seeded

on June 1 and cover crop was roll-crimped on June 6.

Conclusions and Next Steps

These on-farm trials conducted by farmer-cooperators Jack Boyer and Scott Shriver sought to investigate the effect of row-width on soybean yields when rolling a cereal rye cover crop. Boyer terminated his cover crop with an herbicide and rolled the residue into a mulch-mat in select strips. Shriver, who runs a certified organic farm, used a roller-crimper to terminate his cover crop. Both farmers seeded their soybeans into over 11,000 lb/ac of aboveground cover crop biomass.

Boyer saw his best yields where he drilled his soybeans in 10-in. rows and regardless of whether he rolled the terminated cover crop or not (Table 1). “In general, I did not see a benefit from rolling the rye when using my usual seeding method of drilling,” Boyer said. “I believe that this is partially due to the harrow behind the drill performivng some of the same effects as rolling.” Drilling soybeans in 10-in. rows and not rolling the terminated cover crop also netted Boyer the greatest returns on investment from the cover crop (Table 2). Across all treatments, Boyer did not need to manage weeds with an herbicide during the growing season as the rolled and not-rolled cover crop mulch provided sufficient weed control.

Shriver also saw his best yields with the narrowest row-width he used: 7.5-in. (Table 3). Soybean plant populations and yields were drastically reduced with the 15- and 30-in. row-widths. He noted some difficulty planting into very thick cover crop residue (15,165 lb/ac) in early June (i.e., closing the seed trench).

In the future, Boyer plans on not letting the cover crop get as tall and mature before seeding his soybeans due to some harvestability issues with the amount of residue left at the end of the season. “In general, I had more issues with harvesting this field than others, and I believe that it was due to the 6-ft tall rye not decomposing as much as the earlier planted fields, plus more residue to start with.”

References

- CME Group. 2017. Soybean Futures Quotes. CME Group, Inc. Chicago, IL. http://www.cmegroup.com/trading/agricultural/grain-and-oilseed/soybean.html (accessed Nov. 2, 2017).

- Davis, A. 2010. Cover-crop roller-crimper contributes to weed management in no-till soybean. Weed Science. 58:300-309. https://pubag.nal.usda.gov/pubag/downloadPDF.xhtml?id=45407&content=PDF (accessed Nov. 1, 2017).

- Gailans, S., J. Gustafson, and J. Boyer. 2016. Cereal rye cover crop termination date ahead of soybeans, 2016 update. Practical Farmers of Iowa Cooperators’ Program. Ames, IA. http://practicalfarmers.org/app/uploads/2016/11/16.FC_.CC.Cereal_Rye_Cover_Crop_Termination_Ahead_of_Soybeans_Update_2016.pdf (accessed Apr. 19, 2017).

- Iowa Environmental Mesonet. 2017. Climodat Reports. Iowa State University, Ames, IA. http://mesonet.agron.iastate.edu/climodat/ (accessed Nov. 1, 2017).

- Mirsky, S., W. Curran, D. Mortensen, M. Ryan, and D. Shumway. 2009. Control of Cereal Rye with a Roller/Crimper as Influenced by Cover Crop Phenology. Agron. J. 101:1589-1596. https://dl.sciencesocieties.org/publications/aj/articles/101/6/1589 (accessed Apr. 19, 2017).

- Plastina, A., A. Johanns, and M. Wood. 2017. 2017 Iowa Farm Custom Rate Survey. FM1698. Ag Decision Maker. Iowa State Univ. Extension and Outreach. Ames, IA. https://store.extension.iastate.edu/Product/fm1698-pdf (accessed Nov. 2, 2017).

- Smith, A., S. Reberg-Horton, G. Place, A. Meijer, C. Arellano, and J. Mueller. 2011. Rolled rye mulch for weed suppression in organic no-till soybeans. Weed Science. 59:224-231. http://www.soil.ncsu.edu/publications/research/Weed-Sci-59-2_224-231.pdf (accessed Apr. 19, 2017).

- US Department of Agriculture-National Agricultural Statistics Service. 2017. Quick stats. USDA-National Agricultural Statistics Service, Washington, DC. http://quickstats.nass.usda.gov/ (accessed Oct. 28, 2017).