High-Density Grazing and Permaculture: Part 2

Seven W Farm

September 18 2012

Following an enlightening talk on permaculture, participants at the Wilson’s field day on Tuesday were treated to a fabulous potluck lunch. Owner Dan Wilson introduced himself and the rest of the family – all of whom were attending the event. He and his wife Lorna, and his son Torray and his wife Erin, are among the managers and operators of the enterprise. The many hands are an important tool in management: the farm encompasses an organic dairy, pastured beef, lamb, and poultry, and Niman Ranch hogs.

About thirty field day participants and about 20 students from Dordt College piled onto haywagons and were taken for a tour of the operation. The first stop was the farm’s finishing hog paddocks. A-frame huts provide shade and shelter for the pigs, which are raised outdoors according to Niman Ranch principles. The Wilsons have been pasture farrowing for far longer than that, however; the practice was started in 1966 by Dan’s father. Originally the main source of income on the farm, hogs were a way to add value to corn grain. Even though corn prices have gotten so high, they are still valued as a component of the field rotations, working to till and fertilize the soil and control weeds. In fact, one field in the rotation hasn’t been fertilized aside from lime since the 1970s – and still yields over 200 bushels of corn per acre.

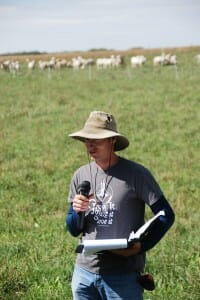

Next the group went down the road, past fields seeded with oats and turnips, to see the grazing mob. Torray started grazing in junior high, and is now a seasoned pro – but still learning and trying new things. He started with a small flock of sheep, over time he added hair sheep for their off-season breeding, hardiness, and low maintenance needs. Now they’re joined by dairy steers; at times he’s had beef cows and calves with them as well.

Torray is well-versed in holistic management and applies those concepts to his grazing stock. Early in the year he plans out the entire rotation – long before the animals ever reach a paddock in the pasture, he’s figured out that they’ll be there. While he has experimented with MIG (management-intensive grazing) and other practices, right now he uses a modified mob grazing system. Temporary electric fences are dismantled daily to allow animals access to new forage. However, they’re also allowed to graze behind them if needed – though they barely do. Torray says that he aims to leave about a day’s worth of forage behind him. This shades the soil, preventing crusting and rain washing; it also leaves leaf area, which will assist the plant in recovering and regrowing. His stocking densities vary with season and forage availability, but he had set up two strips to demonstrate some ultra-high stocking density situations. The mob was moved first into an area where the concentration went up to 250,000 lb/acre of animal; then even further into 1,000,000 lb/acre. Torray explained that packing the animals like that mimics the predator-prey relationship of wild herds on native prairie. The herbivores would crowd together for protection, and thus would trample and crush more forage than they would eat. This tills the soil and adds forage mass back to it, similar to cover crops that are plowed under. Forage will regrow, and the soil is improved. This method of grazing takes time and labor, however: to keep the animals adequately fed at 1,000,000 lb/ac, Torray estimated he would have to move them at least 12 times daily.

The group moved on to see the dairy heifers, out on a different pasture and being followed by a movable chicken coop. Here Torray was able to explain an aspect of his management that fits right into the permaculture ideas: in his pasture mix is chicory, a forb commonly considered to be a weed, but one that is actually quite beneficial. It was rampant in the pasture, but not because it was invading the spaces that “should” be occupied by orchardgrass or clover. Rather it was the most drought-tolerant of the forages, so was the best for providing fodder in a year like this. Its deep taproot system allows it to draw up water to survive, and it also mines minerals from deeper in the soil profile than other plant varieties can.

The tour ended back at the main house, where the milking parlor is located. The family had started milking out on pasture, but after deciding to expand (and not liking dealing with the cold during winter!) they decided to invest in a full parlor. The Wilsons maintain their herd according to organic principles, even though at the moment there’s no organic milk truck coming near enough to pick up from them. They maintain their commitment to their animals’ health and the quality of their products and hope for the situation to change soon.

Until then, they have plenty to keep them busy. Seven W Farm is a shining example of a family’s commitment to sustainability and long-term planning, evident in their productive pastures, healthy swine, and healthy cattle. One day perhaps Torray and Erin’s daughter Audrey – and her sibling, due in February! – will be giving tours themselves.