Field Day Recap: Using Ultrasound as a Tool in Grass-Finishing Cattle

In late September, 28 farmers visited Carney Family Farms to learn about a project Bruce Carney has been conducting with PFI. Before the field day, Bruce ultrasounded a group of his grass-fed cattle twice, at one year and two years of age, to determine carcass characteristics. Each animal was measured to estimate ribeye area, fat thickness and intramuscular fat percentage (marbling). Bruce, and other farmers, want to know if these measurements can help them decide when a grass-fed animal is adequately finished and can be taken to market. It’s not as easy to visually tell when a grass-finished animal is truly finished, as it is with a grain-fed animal. Two handouts using live animal ultrasound and evaluating beef carcasses with ultrasound were given out at the field day.

The group of attendees looked at 14 cattle, seven steers and seven heifers, who are all about two years old and going to be harvested in the next six months. Then, the cattle were ranked from most to least finished, and the rankings were compared to the ultrasound data. The group learned that what you see visually doesn’t always match up to the data. The four most market-ready cattle chosen by visual inspection didn’t necessarily match up to having the highest scores in every measurement taken by the ultrasound, although they did tend to have some of the largest ribeyes.

Field day attendees rank a group of heifers for market readiness on September 28, 2016.

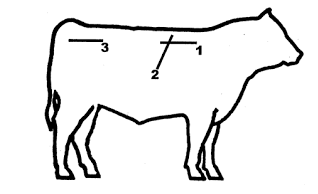

Ultrasound measurements are collected at three points on the animal: 1 – percent intramuscular fat (marbling), 2 – Ribeye area and back fat, 3 – Rump fat (Silcox, 2002)

We noticed that intramuscular fat (IMF) or marbling, significantly decreased in steers from one year to the next, but heifers were more likely to keep the marbling and in some cases, gain more. It seems strange for animals to lose marbling as they get closer to finishing, and Dr. Jim West, a retired veterinarian was at the field day to help explain this. “We know that IMF is the last fat to be deposited and the first to come off, so if the animal is not getting enough concentrate or high-nutrient forage in their diet, their IMF score is going to decrease.” Jim added, “During the first ultrasound when animals were one year old, they had been recently weaned and were probably retaining some of the fat from their mother’s milk, whereas the second ultrasound was taken when they had just come off of August pastures, which can be sparse and low in nutrients.” If the cattle had just come off a pasture of annual species (which includes small grains – sorghum, millet, rye, soybeans), Bruce thinks IMF would have been much higher.

Another interesting fact to note, is that IMF is surrounded by muscles and blood, and the fat can be absorbed into the blood to be used elsewhere in the body. Backfat is not mobilized as easily as IMF is. In the case of heifers having higher marbling scores, Bruce mentioned that heifers put on fat easier than steers and tend to keep it on. Because steers and heifers put on fat differently, it was mentioned that they could be separated and fed in different groups, then harvested at different times.

Bruce Carney explains his two groups of fall 2014 born cattle – how they’ve been grazed, when they’ll be harvested, and how the ultrasound process worked.

Bruce isn’t sure if the ultrasound helped him to actually determine when he should harvest cattle, because he’s still mostly relying on his eye to tell him instead of the data, but he has learned a few lessons. “Looking at the data helps me better understand the importance of always keeping forage quality consistent throughout the animal’s life, which is difficult in a grass-only system. When cattle are close to finished, they must be fed high-quality feed and gaining weight.” Bruce thinks he should plant annuals a month earlier in the early summer so he can improve his forage chain and avoid the summer slump in August.

The group also discussed cattle frame size and the importance genetics plays a role in fat deposition and meat quality. We know that smaller framed animals have a lower maintenance requirement, and once that requirement is met, they can start putting on muscle and fat. Bruce consciously breeds for smaller frame size, but doesn’t have a specific genetic goal in mind.

This was the first of a two-part field day series. A follow up blog post will describe our experience at the Mingo Locker, where farmers were able to look at the carcasses of four of these animals, and compare actual carcass measurements to the ultrasound data. PFI thanks the Iowa Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS) for funding this project and field day.