Field Day Recap: Small Grains, Modest Gains – A Pragmatic Approach

Willie Hughes (right) and father Randy (microphone) share their pragmatic approach to small grains on their farm in southern Wisconsin.

Willie Hughes and family welcomed a diverse group of field day attendees on July 12th to his family’s farm operation of 4700 acres outside of Janesville, WI with these words, “Today we will not see beautiful stands of conventional and organic corn and soybeans but visit the front lines of sustainability: small grains, cover crops and diverse rotations.” Hughes continued to explain that since 1991, when the farm began transitioning fields to organic production, there have been many successes and many failures. “We want to share the good and the bad and the sweet spot of what we currently see working in different parts of our operation.”

Willie stands in a recently harvested winter wheat field.

Wheat

Willie Hughes outlines the complicated rotations on his family’s farm.

Attendees learn about the Hughes’ Lexicon combines.

Nearly a hundred attendees loaded three yellow school buses and headed to the first stop of the day: an organic seed wheat field. The Hughes team had harvested most of a winter soft red seed wheat (variety LCS3204) field on July 11th which yielded 60-70bu/a. This year the field has had significant giant ragweed pressure especially in the long windrows across the field. Willie and his father Randy attribute this to a late fall planting date. “When we couldn’t plant the wheat on time last fall it reduced how quickly the crop grew this spring and therefore its ability to out compete giant ragweed.” Wheat was airseeded and incorporated in last fall. Randy also wondered if they should have drilled the wheat instead of air seeding it. The chicken litter incorporated last fall to fertilize the crop was not pelletized, and some in the audience speculated that the manure source was not fully composted and could have led to the introduction of weed seeds onto the farm. Giant ragweed can be a problem weed in a small grain production system because its large seed germinates towards the end of April.

Giant ragweed pressure was higher this year in the wheat due to a later fall planting date followed by a cool spring.

(Read PFI farmer Tom Frantzen’s comment on his strategies for managing giant ragweed here.) The Hughes direct cut all small grains and wheat when it’s lower than 15% moisture with their Lexicon combine. Prior to starting harvest, they send grain samples to potential buyers to begin marketing their grains. Willie and Randy insist on “marketing the heck out of their grains” to ensure a good return. If they need to improve their farm’s standard operating procedures to insure a higher value seed crop, then they do that to achieve an extra $1/bu premium. Today the Hughes are selling their organic seed wheat for $9-$10/bu. The Hughes have no on-farm storage so crops need to be sold at harvest or until their seven semi-trailers are filled up. Following small grain harvest they will seed 13 lbs/a of ‘mammoth’ variety red clover with one ton/acre composted chicken litter (~35 lbs-N) and then irrigate the field to get the cover crop growing. The Hughes have invested in irrigation systems on fields that are high in sand content. The red clover will be the majority of the nitrogen program for the following year’s corn crop. They are considering frost-seeding ‘medium’ red clover next year into their small grain crop towards the end of February instead of summer seeding their legume cover crop.

Father Randy shares how they cut nitrogen when growing a red clover cover crop with a small grain for their corn crop.

If the Hughes didn’t grow a legume cover crop for their following year’s corn crop, they would apply purchased fertilizer and apply three times the amount during the time the crops need it the most. Since their soils have a tendency to be high in sand, the Hughes are cautious with nitrogen application to reduce its chances of becoming a pollutant or reducing its effectiveness for the corn crop. Randy reminded the crowd that “many of today’s hybrids will respond positively to an application of nitrogen applied after tasseling.”

Stop two was to one of the only industrial hemp production fields in Wisconsin. Willie shared that he’d found a picture of his great-grandma Maude in front of a similar field from the 1940s when farmers grew the crop for the war effort. Willie brought the story full circle and shared that if myths of the crop could be addressed and re-branded, it could become a bigger commodity allowing for improved crop diversity, improved soil and a new farm income stream.

Mark Doudlah and son check out the industrial hemp field.

Legacy Hemp agronomist Bryan Parr co-presented with Willie about the production considerations of this “new” crop. The field had been planted to a fall cereal rye cover crop which was disced with 1T/A composted litter in the spring prior to planting. The hemp seed was air seeded at 32lbs/A and then Tyne weeded plus rolled with a Brillon cultipacker. Many farmers chose to drill the hemp seed. Its seed size is a bit bigger than sorghum seed and although it germinates at 40-45F, Bryan suggested waiting until the ground was 50-55F for planting.

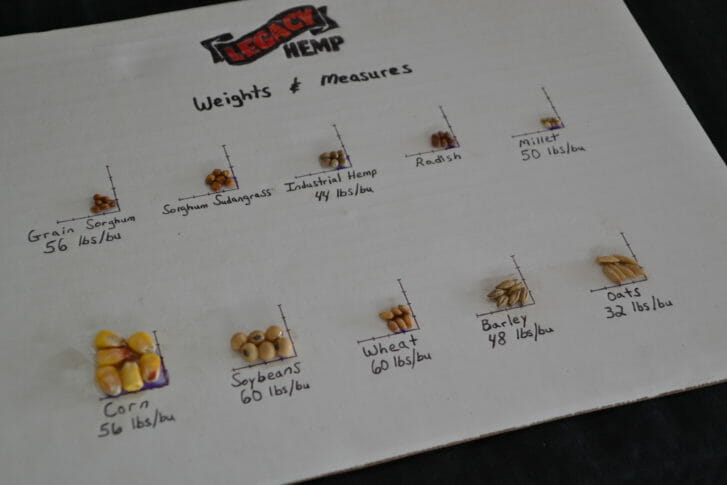

Hemp seed is closest in size to sorghum and much smaller than the small grains. Good depth control at planting is important.

To control weeds in the crop, like all commodities, the goal is to achieve a uniform, quick canopy of the cash crop. Willie had also planted some of the seed at 64lbs/a and feels that area has a much better stand. In the field half the plants had already bolted and died which is how hemp reproduces. Half of the seed lot has male plants that will bolt and die in the summer after pollinating the female plants. Then the female plants are harvested.

Bryan Parr, agronomist with Legacy Hemp, shows a male plant. 50% of the seed will be males that will flower. The female plant produces the seed that is harvested.

Industrial hemp is a 110 maturity summer annual, is day length sensitive and will be harvested at 12-18% moisture. The Hughes don’t plan to swath it, but will instead slowly harvest to ensure the seed is properly threshed. The Michael Fields Ag Institute in East Troy, WI is also growing some seed production fields of industrial hemp and plan to rogue out the dead male plants to see if they can improve total harvest yield and ease of harvest. This fall after harvest the DeLong company will put the seed into totes. The seed will be tested for THC levels. To be registered for industrial hemp, seed must be lower than 0.3%. They hope to harvest about 1000lbs/A with a price of $1.07/lb of finished, dried grain delivered to Legacy Hemp for seed. The seed is a 44lb/bu yield type so it could range from 600lbs/A to 2300lb/A. The Hughes are growing industrial hemp seed for production this year.

Another Wisconsin farmer is growing hemp and shared his tips on planting.

At stop three Willie and Randy explained how they used a spring seeded rye cover crop, keeping it in the vegetative stage, to control weeds for an organic soybean field.

After a quick water break the group headed to a field of soybeans shadowed by two large solar panels.

Dr. Erin Silva with University of Wisconsin Extension explained how organic and conventional farmers have been working with spring planted rye to determine the best date to use it for weed control while keeping it in the vegetative state.

The Hughes have a couple of solar panels on the farm near their main building.

If cereal rye or any winter small grain is planted prior to April in southern WI there is a good chance that the seed will reach a temperature lower than 42F for an extended period of time while it also imbibes water triggering the plant to vernalize. If the seed vernalizes then the following summer it’ll trigger flowering and go into its reproductive phase and produce a seed head. If it does not experience these low temperatures then the plant will stay vegetative and basically die. The Hughes planted 3bu/A of rye on May 2 and then planted the soybeans. Another farmer, Megan Wallendahl described a trial she conducted evaluating spring rye planting date at 10, 5 and 0 days ahead of soybean planting date (5/18) effect on weed control.

Spring seeded rye will stay vegetative and can be a good mode of action for controlling weeds in an organic soybean field.

The earliest seeded rye needed to have extra cultivation to control weeds. Some broadleaf weeds were peeking through when rye was planted the say day as soybean planting and they needed to Tyne weed it. Overall this method reduced the Hughes family three weed control passes. Randy and Willie shared about their overall approach to cover crops and why they are so important to their operation. For an organic farmer, cover crops can provide weed control and nitrogen in the form of green manures. What they are learning in their organic system has informed their conventional operation as well. On the conventional side it has helped them further improve their nitrogen management and reduce their farm’s footprint on the Rock County water quality issues.

Clean organic soybeans with little mechanical disturbance. Spring seeded rye did most of the work.

Nick Baker, Rock County extension agent, presented about water quality concerns for the county and practices that will mitigate some of the issue. Cover crops were at the top of the list. Since they grow in the “off-season” they suck up nutrients that would otherwise leach through the soil or erode off the soil surface and pollute water. 75% of Wisconsin’s water comes from groundwater which can take decades to clean up once on an impaired waters list. The county has pulled together a Nitrate Working Group which has mapped where nitrate levels are high across the county and how wells are testing for N levels. “We need to be careful that our farming practices aren’t direct conduits to the groundwater,” Nick exclaimed. “Using practices like cover crops improve nitrogen management, and other practices to buffer heavy rainfall will help farmers improve their footprint on water quality across the state.”

Rock County, WI has high nitrate levels in the ground water. Practices like cover crops and diverse rotations are important to reducing loss. The Hughes shared their cover crop playbook and PFI staffer Alisha Bower holds the nitrate pollution map of Wisconsin. Darker red means more nitrogen contamination of groundwater.

Knutes Catering fed the crew. Thanks to Albert Lea Seedhouse for their generous donation.

The Buyers and Sellers lunch was next and participants filled their plates from a delicious picnic spread catered by Knutes Catering. Several businesses were available to talk with farmers and others about selling small grains and buying small grain seed. Since marketing small grains is the biggest barrier to increasing this practice on the landscape, PFI has been getting buyers and sellers of small grains together during conference receptions, on conference calls and through our Small Grains Directory available here.

The DeLong Company chatted up potential new customers at the Buyers and Sellers lunch.

Legacy Hemp shares information at the Buyers and Sellers lunch.

Pipeline shares contract information with Willie Hughes at the Buyers and Sellers lunch.

Following lunch Dave Gundlach of the Rock County NRCS showed a rainfall simulator. The display shows the effects of a 4”/hour rainfall’s impact on different farming systems. The display showed how tolerant a fully tilled, no-till, cover crop or small grain treatment was to a heavy rainfall and whether water infiltrated or caused soil erosion.

A conventional tilled field was unable to fully saturate with a 4″ rainfall taken from NRCS’ rainfall simulator trailer. Note the bucket full of brown water that ran off the surface while the empty bucket shows no rainfall infiltrating the soil.

The insert with greater soil coverage is armed and protected for extreme weather events which leads to less soil erosion and nitrogen polluting water bodies. It’s critical that farming systems are able to more and more protect against extreme weather events. Rainfall simulators help show how some systems can withstand extreme weather while others breakdown. It was clear that “the front lines of sustainability” (i.e. crop diversity and cover crops) are going to be needed to hold soil in place and provide high-yielding crop production long-term.

Attendees learn about setting variety trials and check out the Hughes’ corn trial.

Jared Zystro from the Organic Seed Alliance teaches the group about goals for on-farm research.

The group had one more stop to see how the Hughes were evaluating various corn hybrids’ response to three different cover crop mixes. The Hughes planted various cover crops mixes following 2017 wheat harvest and then used them as green manures for corn. Corn hybrids were planted perpendicular to all the cover crop treatments to see if any hybrids performed better. The Organic Seed Alliance (OSA) assisted the Hughes in setting up the trial in a way that they could do more than just observe differences but collect valuable data to determine whether there were “true” differences between each hybrid’s yield performance. OSA explained what to consider when deciding to do a variety trial. Read more about the OSA playbook for on-farm trial design here On Farm Workshops Handout_Hughes. Are your goals to evaluate your standard corn hybrid to a new one? Then chose a paired comparison and replicate the pairs at least three times across your field. Do you want to evaluate drought stress? Or response to nitrogen? Or emergence percentage? You might want to test 6 hybrids, but due to the size constraints needed to conduct a fully replicated trial, Jared Zystro from OSA suggested just including a “check” hybrid a couple times within the plot and then evaluating yields or drought stress or disease tolerance from that “check” hybrid to determine differences. Jared reminded us that “every farm should be a research farm so that we don’t put all our eggs in one basket.” This can lead to improved seed selection and potentially improved profitability on your farm. Don’t forget to write down where you plant each hybrid and map out your design so that during your harvest you can correctly measure each hybrid’s yield.

Willie and Randy share more about the corn hybrids they plant. Quick emergence and yield are top priorities for the Hughes.

Matt Leavitt with MOSES, reminded the group about the rules for sourcing organic seed: OSA Field Day Topic Areas of Discussion. Organic farmers are allowed to purchase untreated, conventional seed if after checking three sources not enough of the preferred hybrid or variety is available. However, Matt shared important advice, “if organic farmers do not purchase seed grown and bred under organic conditions then the earnings from that sale do not support organic breeding which could result in reduced yield performance for organic growers.” If seed companies have demand for organic corn or soy varieties they will work to meet that demand with better yielding products. Organic farmers need to make sure they are supporting that industry which in the long-term can help them with greater access to genetics that perform best under organic conditions.

Non-gmo white corn hybrid destined for the chip market.

Our final two stops were a look at the non-gmo conventional white corn field and a short presentation by Dr. Silva about items to consider when transitioning to organic production practices. The Hughes white corn variety has good yield potential, has a tendency towards double ears, and demands a higher level of harvest management to avoid damaging the kernels. If the white corn kernels are nicked during harvest the “masa” corn flour used to make corn chips will result in a chip holding too much oil and taste greasy. The pericarp on the grain needs to be maintained so that the moisture content of the grain during milling does not give this “off” flavor. Inside Dr. Silva ended the day with information about what the steps are to transitioning to organic.

Practical Farmers of Iowa thanks the Hughes Family, Dr. Erin Silva’s lab group, Albert Lea Seed House for sponsoring the lunch and our co-sponsors the Organic Grain Resource and Information Network. OGRAIN is an educational framework for developing organic grain production in the upper Midwest.