Conserving a Farm’s Legacy

Conservation easements can protect landowners’ farm visions while opening the door for the next generation.

When deciding strategies for land transition and preservation, the myriad options available to a landowner might seem overwhelming. One tool many PFI members have used to successfully realize and protect their visions for their lands is a conservation easement.

A sign demarcates land that has been protected with a conservation easement. (Photo courtesy of NRCS)

What Is a Conservation Easement?

There are many types of easements. The most common type is also referred to as a right-of-way, which provides for access to or across private property. A conservation easement, however, is different and specific. According to the Land Trust Alliance, a conservation easement is a “voluntary legal agreement between a landowner and a land trust or government agency that permanently limits uses of the land in order to protect its conservation values.”

The key, says Erin Van Waus, conservation easement director with the Iowa Natural Heritage Foundation, is that a conservation easement exists in perpetuity. “No matter who owns your land in the future,” Erin says, “that easement and its requirements remain with the land forever.”

Why Use a Conservation Easement?

“Top of the list for many landowners is peace of mind,” Erin explains. “They want to know that this farm that their grandfather put together, or the place they first went turkey hunting, will be like that forever, and that no matter who owns it into the future, this place that’s near and dear to their heart will be protected.”

PFI member Beth Henning, who has experience with different types of conservation easements established with different organizations, echoes that sentiment. “It’s a great relief to me to know the land is protected after I’m gone,” Beth says, referencing both her personal and family properties that are protected by easements with INHF and the Sustainable Iowa Land Trust, respectively.

“Top of the list for many landowners is peace of mind. They want to know that this farm that their grandfather put together, or the place they first went turkey hunting, will be like that forever, and that no matter who owns it into the future, this place that’s near and dear to their heart will be protected.” – Erin Van Waus

On Beth’s personal land (90 acres in Guthrie County), she and her husband put considerable work and effort into restoring prairie and savanna. In order to protect that habitat – and preserve the work and toil they invested in the property – Beth wanted to ensure the land wouldn’t be developed or used in a way contrary to their vision for the property. She worked with INHF to develop the easement language. As a result, the majority of the farm, save for 8 acres reserved for a homestead, will never be farmed or developed.

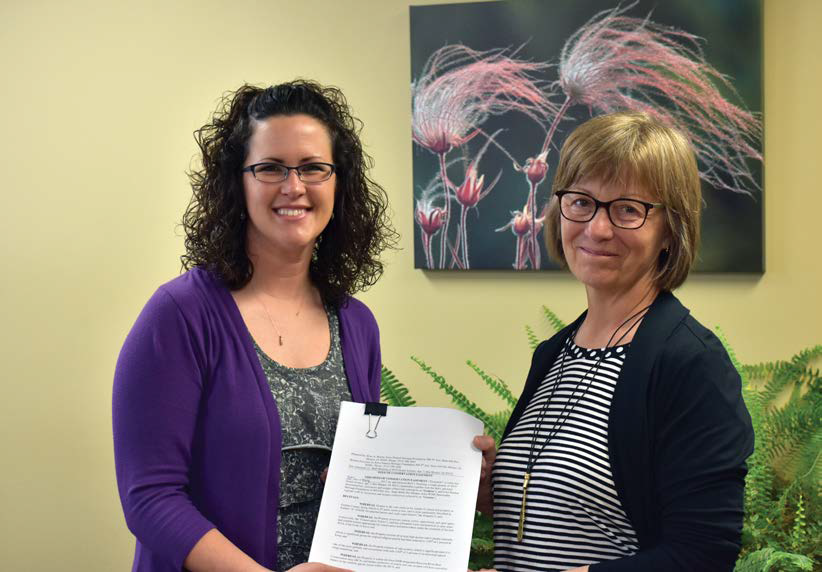

Erin Van Waus (left), conservation easement director with Iowa Natural Heritage Foundation, poses with Beth Henning holding a copy of her conservation easement agreement.

Beth’s family property has a slightly different story. Owned in partnership with Beth’s sisters and a nephew, the family wanted to see the farms stay in sustainable production without being developed. “We were at the point where we weren’t able to take partnership into the next generation and we weren’t sure how much longer we wanted to manage the farms, but we just didn’t want it to be sold off as farmland to the highest bidder or developed,” Beth says. “That’s when we contacted the Sustainable Iowa Land Trust.”

The agricultural easements Beth and her family placed on the properties in partnership with SILT provided peace of mind when they began the process of selling the farms. “Without the easement, you can feel pretty confident that you’re selling the farm to someone who shares your values – but you don’t really know what’s going to happen down the road when that land changes hands two or three times,” Beth explains. “With the easements, we could be sure that our vision for the land was going to be realized forever.”

“It’s a great relief to me to know the land is protected after I’m gone.“ – Beth Henning

In addition, because easements can lower the market value of the land significantly – 40% reductions in value are not unheard of – they can be a useful tool for succession and transfer planning. For example, one of Beth’s family farms was sold to a young local farmer and the other was purchased by a nephew, which kept that particular farm in the family.

In both cases, Beth says it would not have been possible for those buyers to afford the land without the conservation easements first lowering the appraised value. Because the price of the land was more attainable, Beth and her family members were able to pursue land transitions that fulfilled their goals and visions for the farms.

There are also tax benefits associated with conservation easements. In Iowa, landowners who donate conservation easements can access both a state income tax credit and a federal income tax deduction. Rarely, however, do the tax benefits outweigh the loss of market value or upkeep costs associated with the easement. As always, landowners should speak with their accountants or tax advisors to get a better idea of what kind of tax benefits they would see as a result of pursuing a conservation easement.

Living With a Conservation Easement

The realities of living with a conservation easement can be daunting. “Some people are reluctant to pursue a conservation easement because they don’t want to tie the hands of their children or grandchildren,” Beth says. She and her family worked closely with the farm operators and potential buyers to make sure everyone was comfortable with the terms of the conservation easement on their farms.

Shannan Potts and her husband, Rod, are the farm operators on one of the farms Beth and her family put under easement. Shannan says that because the easement aligns with their farming methodology, they’ve found it actually impacts their operations very little. “We were pretty involved in drafting the easement,” Shannan says. “It was super informative being involved in that process, and it turned out the easement didn’t actually change a single thing for our operation.”

Nonetheless, Shannan recognizes there is still potential for the easement to impact the operation in the future. “It’s a great fit for us now,” Shannan says, “but when you try and look into your crystal ball into perpetuity, things get murky.”

Another key aspect of living with a conservation easement is regular review of the property by the organization or agency holding the easement. These inspections are often done annually and are conducted to ensure that the terms of the easement are being followed. For both landowners and operators, the idea of routine inspections may seem intimidating. In practice, though, the visits can be friendly and informal.

“We were pretty involved in drafting the easement. It was super informative being involved in that process, and it turned out the easement didn’t actually change a single thing for our operation.” – Shannon Potts

“The first site visit seemed big and scary,” Shannan says, “but it turns out it wasn’t big or scary at all.” The first site visit, she explains, ended up involving mainly the landowner, SILT staff and Shannon’s husband driving the property to look at what was going on. “We have high hopes that all inspections are as simple and straightforward as the first one.”

Although the easement on the land Shannan and her husband farm doesn’t affect their operations, easements do have real potential to affect property management in a variety of ways, even when that management is aligned with the spirit of the easement.

For instance, on Beth’s personal property, which she and her husband had worked to restore to native habitats, Beth suddenly found herself having to consult with Iowa Natural Heritage Foundation, which holds the easement, before taking action. “It becomes a process,” Beth Henning says, “and is a bit of an adjustment after 25 years of managing the land how I wanted.”

While she’s still adjusting to that requirement, she adds that the open communication she has with INHF staff is critical to working through – and hopefully preventing – any issues. “It’s a process of accommodation and compromise,” Beth says. “I’m now managing this land in partnership with the holder of the easement.”

Choosing a Conservation Organization

Conservation easements always involve working with a conservation organization –typically a government agency or a land trust, which is a private, non-profit group that actively works to conserve land. The role a conservation organization plays might vary, but in general it is responsible for ensuring that the restrictions and stipulations within the easement are adhered to after the easement is recorded.

Beth Henning poses on her personal farmland near Guthrie County. She and her husband have worked to restore native prairie and savanna on the land.

When choosing the organization to work with, it’s important to note that not all organizations are identical, and different land trusts or agencies might have different priorities. Iowa Natural Heritage Foundation, for example, works broadly with all types of easements, including working lands agricultural easements. Sustainable Iowa Land Trust, on the other hand, is an organization focused specifically on protecting land for sustainable food production.

Accreditation is another factor you could use when deciding which organization to work with. At its most basic level, accreditation is a certification given by an organization like the Land Trust Alliance that indicates the accredited organization meets certain minimum standards for land conservation activities. Accredited organizations have demonstrated that they use best practices for land conservation, and this certification can serve as reassurance that the conservation organization is effective at protecting land. INHF is an accredited land trust, while SILT, as a newer organization, is scheduled for accreditation in 2020.

The Role of the Conservation Organization

Many land trusts, including INHF and SILT, will work with landowners through all phases of the easement process. Erin Van Waus with INHF notes that the process often starts with a simple call or request for more information.

“The first step is usually to get out on the property with an interested landowner and hear from them what their vision is for the property,” Erin says. “From there, we can assess whether the property is a good fit for our program.” During this time and throughout the entire process, INHF strives to serve as a sounding board for landowners, and a confidential place where they can ask questions with no strings attached.

Joe Klingelhutz, farm specialist with SILT, describes a similar process. “We can provide feedback, provide the baseline documentation, develop suggestions for landowners,” Joe says. “Then we’ll work with the landowner to develop language, decide the boundaries and stipulations of the easement and generally work with the landowner to decide what’s going to be allowed and disallowed.”

Joe and Erin both note, however, that every landowner is responsible for consulting with their own attorney or accountant before the easement is finalized. “As a land trust, we can’t give any legal or tax advice,” Joe says. “It’s important that landowners review all the documentation independently before the easement is executed.”

Working through the details of an easement can be a long process involving many perspectives that need to be considered, but the land trust’s work truly begins once the easement is officially recorded. That’s when the monitoring responsibilities kick in.

“After the easement is executed, SILT’s role is to monitor and enforce that easement in perpetuity,” Joe explains. “Our goal is to walk the property every year and make sure things are progressing in accordance with the easement.” If a property is sold or changes hands, both INHF and SILT will work with potential buyers to make sure everyone understands the easement and its requirements. In a worst-case scenario, the land trusts may even use the courts to enforce the terms of an easement.

“We’re here to guide every landowner through the process in order to achieve their goals,” Erin says. “It’s a really neat partnership that allows for land protection while still keeping the land in private hands and protecting the vision of the landowner.”