Funding Conservation: Making working lands programs work for you

The farm bill (now technically the Agricultural Improvement Act of 2018) is a massive piece of legislation signed into law roughly every five years. Amongst its many provisions is what’s known as the Conservation Title – Title II – which authorizes a host of conservation programs and is perhaps the single largest source of legislated conservation funding in the world.

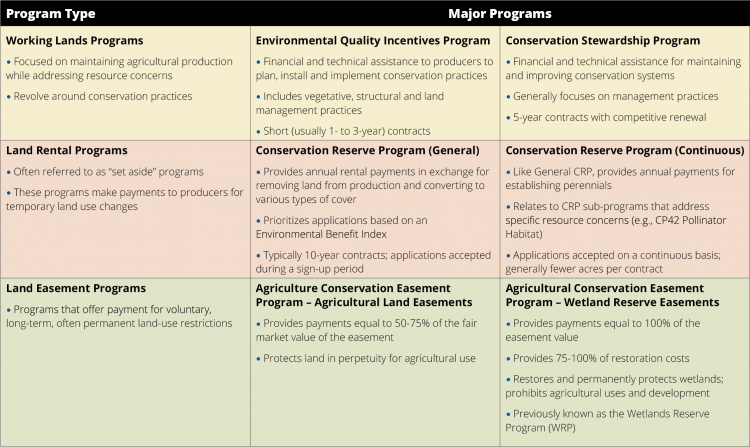

Falling roughly into three broad categories (see the table below), these programs provide financial and technical assistance to producers and landowners for a variety of purposes. Two of the most popular conservation programs today are the Environmental Quality Incentives Program (EQIP) and the Conservation Stewardship Program (CSP).

These two initiatives are commonly referred to as “working lands” conservation programs, and they are designed to encourage conservation activities on privately owned lands that are in active agricultural production.

Environmental Quality Incentives Program

The Environmental Quality Incentives Program is one of the largest federal conservation programs by dollar value. In federal fiscal year 2018, EQIP (usually pronounced “equip”) provided $1.87 billion in financial and technical assistance. That money was used for a variety of on-farm practices, from construction of manure management systems and cover crops to prescribed grazing, riparian buffers, high tunnels and everything in between.

If you can think of a conservation practice, EQIP has likely provided support for it – there are several hundred conservation practices to choose from, many of which can be combined as needed to meet conservation goals and address resource needs. EQIP contracts usually last one to three years (there are exceptions) and provide payments, typically 50-75% of estimated total cost, for specific practices or activities.

Conservation Stewardship Program

The Conservation Stewardship Program is by some measures the largest private lands conservation program by acreage – over 70 million acres are covered by CSP contracts. Established in 2002 through the Farm Security and Rural Investment Act, the program supports on-going and new practices by farmers who are implementing whole-farm conservation systems.

To compete for a CSP contract, producers must demonstrate a high level of conservation – CSP is often considered an “above and beyond” program, designed to reward farmers for beneficial management practices across the whole farm. Conservation Stewardship Program contracts last five years and can be competitively renewed.

Rob Stout (left) and his stepson, Alex Zimmerman, raise corn, soybeans and hogs in Washington County, Iowa.

PFI member and farmer Rob Stout has participated in different state and federal cost-share programs. He and his stepson, Alex Zimmerman, farm about 1,000 acres of corn and soybeans in Washington County, and they also own around 9,000 hogs.

Rob says he first learned about the Conservation Stewardship Program, which was new at the time, from his local Natural Resources Conservation Service staff. Because of his ongoing conservation efforts and his desire to do more, he says CSP was a natural fit. Rob is now roughly halfway through his second five-year CSP contract, and so far he’s been satisfied with the program.

“Even the first time around, some things I was doing already,” Rob says. “I had only just got started in cover crops, so that first contract I did more acres. I also did some fall nitrate tests and fine-tuned my nitrogen application.”

As mandated by the program, Rob’s second contract required him to add an additional layer of conservation. He chose to add more diverse cover crop mixes that included peas, radish and oats, among other things. He also started doing some soil health testing to better understand how his farm’s soil is reacting to his suite of conservation practices.

Through his CSP contract, Rob receives an annual payment each year for five years in exchange for adopting a suite of conservation practices across his farm. The payment amounts vary based on the practices being implemented, but this broad-based compensation is the primary way in which CSP differs from EQIP.

Where EQIP generally offers only short-term contracts to pay for specific conservation practices, many of which are structural, CSP offers longer-term contracts designed to provide cost-share for a system of whole-farm management.

“I’m not sure how they come up with the number,” Rob says, referring to the payment amounts. “But generally it works out okay. Sometimes it can be tricky to cash-flow expenses like buying cover crop seed while you’re waiting on the CSP payment.”

“It’s nice to get a little cost-share out of [the Conservation Stewardship Program]. A lot of the things I’m doing, I don’t see the benefit on my farm. Those benefits are downstream and in the future, so I don’t feel bad about taking the cost-share.” – Rob Stout

Overall, however, Rob says he’s happy with the way CSP works. If he could change anything about the program, he would like to see farmers get more credit for work they’re already doing. To illustrate his point, Rob explains that over the course of his first CSP contract, he and his stepson really increased their conservation efforts outside the scope of the cost-share program.

In other words, they decided to do more conservation on their own without any government support. When the time came to renew their CSP contract, however, Rob feels they didn’t get enough credit for that significantly expanded conservation work.

“They want you to add something new,” Rob explains, “but we were already doing a lot. People have really stepped it up on their own and it seems like maybe they’re not given enough credit for that.”

Despite this, Rob appreciates the program and intends to pursue another contract renewal. But he adds that while CSP has been good to him, it hasn’t been his primary conservation motivator.

“I’ll keep doing what I’m doing anyways,” Rob explains. “I don’t get cost-share to do all I’m doing anyways, but if money is available I’ll take it. It’s nice to get a little cost-share out of it. A lot of the things I’m doing, I don’t see the benefit on my farm. Those benefits are downstream and in the future, so I don’t feel bad about taking the cost-share to reap some of the rewards.”

This material is based on work supported by the U.S. Department of Agriculture, under agreement number NR196114XXXXG003.

Any opinions, findings, conclusions, or recommendations expressed in this publication are those of the the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the the views of the U.S. Department of Agriculture. In addition, any reference to specific brands or types of products or services do not constitute or imply endorsement by the U.S. Department of Agriculture.