Linking Livestock to Land

For non-operator landowners and tenants alike, adding livestock can be a win-win.

At one time, the vast majority of farms in Iowa included livestock. Today, however, livestock are an afterthought for many current non-operating landowners – those who don’t actively farm. But the evidence, both anecdotal and empirical, is building that reintegrating livestock onto the landscape can be a powerful tool to realize the goals of landowners and farming tenants alike.

Arlyn Kauffman and his cousins, Andrew Yoder and Mark Yoder, farm and raise livestock in Decatur County. For the past few years, the trio have rented cropland from an out-of-state landowner. But Arlyn and his cousins had a vision for other ways they could use that land: What if they could also graze the property and gain much-needed winter forage for their livestock while improving the soil health of the property’s cropped acres?

The arrangement would be a win-win, benefitting the farmers while proferring the landowner additional income and improved soil health on the land over time.

Before the vision could become reality, Arlyn, Andrew and Mark had to confront some challenges and work with their landlord to address his concerns. The main obstacle was the landowner’s concern that the presence of livestock could endanger one of the primary uses for the property: deer hunting. But by initiating a dialogue with this landowner, Arlyn and his cousins were able to identify a path forward that addressed both parties’ concerns – and will hopefully result in long-term benefits for both tenants and landowner.

Andrew Yoder, left, and Arlyn Kauffman pose with cows they graze on land they lease from their non-operating landlord.

It’s Not the Cow, It’s the How

Livestock, particularly cattle, suffer from a somewhat tarnished reputation. Media coverage is often not kind – sometimes rightly so: When managed improperly, cattle can have serious impacts on the environment. In recent years, however, apprehensions around grazing have dissipated, due in large part to increased awareness and knowledge of proper grazing management. It is not an overstatement to say that management is absolutely critical when using grazing as a tool to manage land.

That said, grazing and livestock management can be complex and difficult to understand. Even the lexicon is dense – you’ll often hear rotational grazing, prescribed grazing and adaptive grazing management all used to refer to the practice of keeping livestock on the move and never in one place for too long.

Managing the intensity, frequency, duration and timing of grazing events has the potential to provide a plethora of benefits, including improving the aesthetic and value of the land while providing extra forage for livestock.

Start With Your Goals

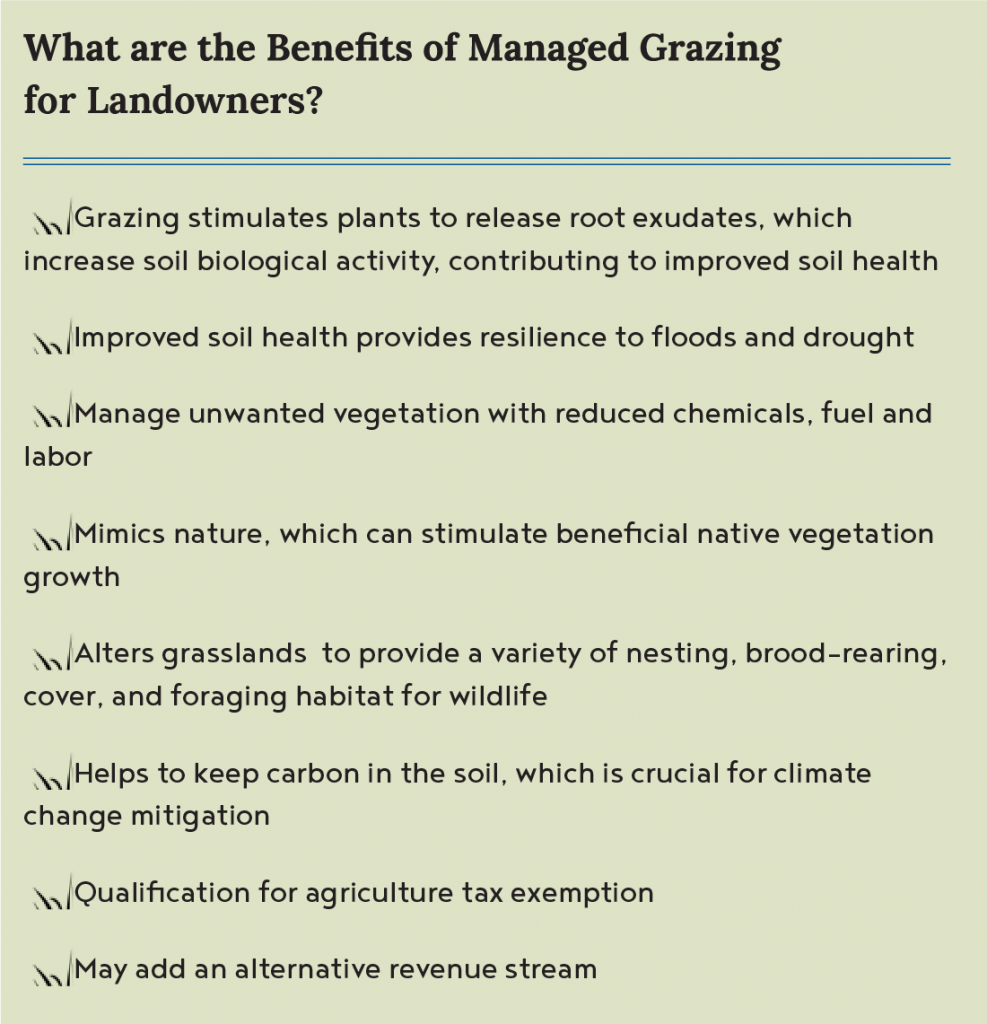

Whether you’re a landowner or tenant, start with your goals for the land to help you decide whether grazing is the right land management tool. For landowners, livestock can provide extra revenue, improve wildlife habitat and boost soil health.

With goals in mind, you can design a system that integrates livestock to meet your vision. Keep in mind that while integrating livestock itself might not be your top priority, it might be a priority for your tenant. If that’s the case, working together to add livestock could help you both build a stronger long-term relationship.

For Arlyn and his cousins, accessing winter forage and improving soil health were the primary motivations. Their landowner, however, lives in Arkansas and visits his land in south-central Iowa to recreate and hunt at different times throughout the year.

While providing forage for livestock wasn’t a priority, boosting soil health, extra revenue and building a stronger relationship with his tenants were all incentives. “We approached him from a soil health perspective, explaining how grazing can improve the value of his farm,” Arlyn says. “But we also had to make the case that it wasn’t going to hurt the hunting.”

“We approached [our landlord] from a soil health perspective, explaining how grazing can improve the value of the farm. But we also had to make the case that it wasn’t going to hurt the hunting.” – Arlyn Kauffman

Initially, Arlyn’s landowner needed some convincing; he was worried about degrading deer habitat, believing cattle and deer don’t mix. “We agreed to graze cows in February and March, then remove them in order for vegetation to fully recover by hunting season the next fall,” Arlyn says. “We also agreed to fence out a 15-acre spot that is special to the landowner because it’s where deer bed down and browse and he doesn’t want cows to ruin it.”

Through open conversation and dialogue, Arlyn was able to come to a compromise with his landowner that resulted in both sides’ goals being met – and opening the door to a stronger long-term relationship. Arlyn says his landowner’s mind has already changed for the better. “Now it is up to us to keep doing things that reinforce his new opinion and not jeopardize it in any way.”

Find A Grazier

For Arlyn’s landlord, the transition to having cattle on the land was eased by the fact that Arlyn and his cousins were already renting the cropped acres they hoped to graze. The trio also grazes on rented ground elsewhere and are experienced with managed grazing. Arlyn identified an opportunity to graze cover crops on the cropland portion of the land, as well as the grassy corners, waterways and woods on the property.

Because the farmers already had a relationship with their landlord, they felt comfortable approaching him openly about grazing. For many landowners, however, reintegrating livestock onto the landscape is not always so straightforward.

As with Arlyn and his cousins, the simplest way to take advantage of grazing is to work with neighbors or tenants who already have livestock. If this is not an option, ask your local Soil and Water Conservation District office, Natural Resources Conservation Service representative or local Cattlemen’s Association chapter for suggestions of graziers who have experience in leasing land and employing managed grazing.

You could also take a summer drive around your county to see who is grazing and stop to ask if they are interested. Alternatively, PFI is currently working to develop the Midwest Grazing Exchange, a website to match landowners and row crop farmers with graziers – like a dating app for land and cows – which will go live this summer.

Grazing Leases

At its most basic level, a lease is an agreement for one party to use land owned by another party; in practice, things are more complicated. Like crop leases, grazing leases can vary considerably. For Arlyn and his landowner, an oral agreement for this first year of grazing was sufficient for both parties to feel comfortable with the arrangement. If the idea of an oral agreement is disquieting to either landlord or tenant, the best practice is always to use a written lease.

Oral or written, grazing leases require you to consider several key points that don’t usually come up, or are less common, in a crop lease, such as stocking limitations and timing; liability; use of vehicles or all-terrain vehicles on the property; and landowner rights and reservations. These are just a few points to consider; as always, landowners and tenants should both seek legal advice for questions about what or what not to include in a lease.

Stocking Limitations and Timing: Any grazing agreement, written or oral, should include the number of animals permitted to graze the property in question – as well as when animals are permitted on the property. Arlyn and his landowner agreed to a high-density stocking rate over a short period of time in late winter.

While this structure worked well for them, it’s not the only stocking scenario. Different stocking rates – and the timing of grazing – can have variable effects on the property. These scenarios also benefit cattle in varying ways. Here again, it’s vital that landowners and tenants discuss their respective goals so that each side can work towards solutions that meet both needs.

Liability: Whenever a land situation involves people, animals or other objects moving around on the landscape, liability concerns always come into play. The concerns are handled in many ways in a grazing agreement, from indemnification, “hold harmless” and “breachy” (read: escape artist) livestock clauses to requirements for regular fence and gate maintenance.

Liability: Whenever a land situation involves people, animals or other objects moving around on the landscape, liability concerns always come into play. The concerns are handled in many ways in a grazing agreement, from indemnification, “hold harmless” and “breachy” (read: escape artist) livestock clauses to requirements for regular fence and gate maintenance.

The end goal is for both sides to feel comfortable with their responsibilities under the lease. This includes ensuring both parties understand and accept the terms of activities each signatory to the agreement must perform, as well as who will be responsible in the event of a lawsuit. “This farm is not along a highway and there is very little traffic,” Arlyn says. “So a verbal agreement was sufficient because liability was not a concerning factor for either party. If it were, we would have gone with a written lease.”

Use of vehicles or ATVs: With a cropping lease, it is assumed that the tenant will be operating machinery in the course of agricultural production. With a grazing agreement, that assumption is not always valid. Both landowners and tenants should consider the degree to which all-terrain and other vehicles will be allowed on the property. For a variety of reasons, these vehicles can be vital to many livestock management and transportation strategies, so it’s best if graziers and landowners address this issue up front rather than be surprised down the road.

Landowner rights and reservations: Without any qualifications or exceptions, a lease agreement for a property assumes the tenant has exclusive possession of the property being leased. This means that unless specified, the landowner cannot legally use the property for the duration of the lease agreement.

Most agricultural leases, however, include reservations for the landowner to enter the property to inspect the premises, sometimes with or without notice. Landowners who wish to continue using the property for recreation – such as hunting – should specifically reserve that right in any agreement.

When negotiating their grazing agreement, Arlyn, Mark and Andrew showed their landlord how their cows on their home farm know to respect the electric wire.

Economics

The economics of every lease differ, but by talking to each other, landowners and tenants can come to an agreement that is financially viable – or even profitable – for both sides. In exchange for grazing rights, Arlyn and his cousins agreed to pay for and plant cover crops on the property. The landowner receives the long-term benefits of soil health while the farmers recieve the short-term benefits from grazing.

Since Arlyn, Mark and Andrew have access to this land for grazing in February and March, they have the potential to save three round bales of hay per day during those months. Presuming they graze for 20 days, this means they save 60 bales of hay – which, with hay valued at $75 per bale, equates to a savings of $4,500. Thus, in addition to the benefits for the land and cattle, both parties financially benefit from the arrangement.

Make it Work for You

Agreements, either oral arrangements or written leases, can be incredibly flexible. Despite this, many landowners and tenants end up agreeing to boilerplate stipulations that don’t work well for either side, or don’t meet specific needs, because they’re hesitant to start the conversation.

Opening a line of dialogue can be difficult, especially when it can seem like landowner and tenant speak different languages. But a willingness to communicate openly usually results in a better agreement that can lead to a healthier long-term relationship.

For Arlyn and his landowner, a few key points had to be negotiated before finalizing their agreement so they could ensure both sides’ needs were being met. The landowner’s top priority was preserving the quality of hunting and the wellbeing of the deer herd on the property.

Arlyn and his landowner were able to agree on stock density and timing, abating the landowner’s concerns about deer-cattle conflict while simultaneously allowing Arlyn and his cousins to meet their goal of providing stockpiled and cover crop forage during the winter – a critical link in their year-round forage chain.

Another sticking point was the use of single-strand electrified wire to contain the cattle. Arlyn addressed this concern by taking the landowner to see the cows on their home farm. The landowner was able to witness the well-trained cows respecting the wire, which eased liability concerns and ultimately helped him feel comfortable agreeing to the use of single-strand wire to keep cattle in.

Communication is important, and Arlyn believes that keeping his landowner apprised of the situation on the farm is critical. He regularly communicates with his landlord, texting him when they aerially seed cover crops on the cropped acres and when the cover crops emerge. Arlyn also plans to take before, after and during pictures of the cattle grazing the property.

By keeping the landowner engaged and up-to-date, he hopes to further cement the relationship so that he and his cousins can continue grazing the property. This communication builds on the relationship he’s already established with his landlord, ensuring a productive and profitable partnership into the future.