Farmer Stories

On the evening of Saturday, Jan. 23, a crowd of expectant guests tuned in from couches, kitchen tables and other cozy nooks across multiple time zones to hear six PFI members share their personal stories live during the concluding event of “Coming Home,” PFI’s 2021 virtual annual conference.

Sharing experiences and lessons learned with one another is part of PFI’s culture. At events, the side stories and moments of personal connection are just as valuable as any field demonstration. As last year’s virtual field day season wound down and we began thinking about the annual conference, we realized how much we missed those treasured interactions, and we had a hunch that you might, too.

We recruited six members – Jill Beebout, John Gilbert, Lorna Wilson, Darla Eeten, Michael Eeten and Jathan Chicoine – to tell tales of farming, connection and remembrance. Hosted by PFI member Wade Dooley framed snugly by a warm fire, these farmers channeled their singular experiences into 90 minutes of memorable, heartwarming, humorous and powerful stories about starting to farm, connection to land, raising children on the farm, picking green beans and learning from the lifeways of bison.

Connection flowed as the online audience chimed in with expressions of shared relief; affirmations of “so beautiful” and “wonderful story”; collective remembrances of snow caves and blizzards; shared jokes; and plenty of digital applause. For those who were unable to attend, or wish to experience these powerful and delightful stories again, we are sharing them on the following pages. The stories are largely preserved as orally presented, with light edits for style and clarity.

My husband, Sean Skeehan, and I moved to the farm on April Fool’s Day 2005, and if that isn’t an augury of things to come in the birth of a farm, I don’t know what is!

Now, we already look like the punchline to a farming joke. Sean is six-and-a-half feet tall, more than a foot taller than I am. He walks at about half the speed that I do and is far more intellectual and considered in his speech and actions. To add to the irony, neither of us grew up on a farm. We both have theater degrees and spent years working at theaters around the country, which surely prepared us to start a farm – we just went from the non-profit world to the no-profit world. But at least we can act like we know what we’re doing.

So we moved to farmland owned by my family, and acted like we had a plan. What could possibly go amiss? The trial by tiller, the dump wagon debacle, the hay rack wreck. And those were just the poetic examples. What we did was make every silly beginner mistake possible. Luckily, we all survived that first season.

Season number two: Now can really act like farmers! Among other things, we were determined to build our first high tunnel. There was a lot of ground prep, here in hilly southern Iowa. Luckily, we had a dad with equipment and real skills. But when the day came to auger holes, Dad wasn’t available and rain was coming late the next day. As he left the farm, Dad rolled down his window and said, “no worries, you can do it!”

So we gathered up our collective courage between the two of us and marched down the hill towards the skid steer, anxiety mounting but both of us acting like we knew what we were doing. I scooted into the driver’s seat and started her up. I hooked onto the auger without an issue, but Sean couldn’t get the locking levers down. He climbed onto the arms to try to step them down, but his ginormous size 13 boots were too big to fit on the levers. He nearly got stuck, big albatross arms wheeling around. Well, this wasn’t getting us anywhere. So I scampered out and he slowly folded himself into the driver’s seat. A couple of quick jumps on the levers. Success!

Then there were the hydraulic connections. They’re in an awkward position and nothing we did could get them to seat. There was no thoughtful language now, just snarling, swearing, grunting and snapping.

“Just push it!”

“I am pushing it!”

“No, here, grab it here. No here, RIGHT HERE!”

Then a phone call to Dad, whose typical unruffled response of “yeah, that connection can be a bugger” was a little bit of a balm on our newbie nerves. And a second call to Dad, who replied, “Oh, I should have told you to try releasing the hydraulic pressure. That should do it.”

So we tried to do as suggested. The hydraulic fluid oozing out made everything go more “smoothly.” At least our conversation was well lubricated: those words just slid right out, words I can’t repeat here. I bet we fought with that crazy thing for half an hour before we heard the magic “click.”

Then there was the second connection, which only required a little more lubricated language. And then, YES!! We were triumphant, and we hadn’t even done anything yet.

Finally connected, Sean slowly rolled up the hill to the high tunnel site, with the auger sticking out front like some growling, single-horned beast creeping across the farm. I would say like a unicorn, but there was nothing sparkly or magical about that day, just a slowly building wave of apprehension. I scurried after him with an armful of tape measures, level, shovel, jobbers and who knows what else. We were going to do this! We were determined, and still we were clueless.

As I juggled up to the site with my load of tools, Sean had carefully lined up to the first post location and was raising the boom on the skid steer. If you’ve never seen or used a skid steer auger, it is different than a post hole digger on a tractor. It mounts on the attachment plate on the boom arms in front of you, then the boom is raised up and the plate tilted down so that the auger is hanging straight up and down. Ours is a 5-foot-tall auger, so the boom has to be raised well above my head for the auger to have space to hang clear to move into position.

So the boom slowly rose – and almost as though it was connected, so did my anxiety level. Somehow, that didn’t happen when my dad was driving. But we were going to do this!

Then the auger started to tilt down, slowly, until the plate was nearly parallel to the ground, and then SLAM! The entire auger dropped like a 300-pound metal spear, the point striking the frame of the skid steer, right between Sean’s knees. Everything stopped. I froze, watching the auger balance there on its tip, hanging from the hydraulic hoses. Sean was dead still, his mouth and eyes wide open. Everything stopped. The birds quit singing, the wind stopped blowing, my heart stopped beating. “Holy hel … lo! Are you ok?” I asked when I could breathe again. Silence. Then he closed his mouth and blinked his eyes. Cautiously, he replied, “Fine. It didn’t even touch me.” But now what do we do? If he lowers the boom, it will change the angle of the auger, causing it to slide towards him. But if he raises it to allow it to swing back out, the hoses may fail and the whole thing could fall on him. I had never been so scared in my life.

There was no one else on the farm and we were stuck. After studying the problem from his precarious seat, Sean finally decided all we could do was risk lifting it up. I scurried down to the barn and brought back a length of rope that I tied to the auger. Hopefully, this would act as a guide and I got ready to yank that thing for all I was worth if it started to fall. I’m sure my 130 pounds would have been a very effective counterweight had it been necessary. Luckily, it wasn’t. The boom lifted slightly, the auger swung free and Sean gently lowered the boom with just a couple gentle nudges of his toe on the control pedal. All the while, I was hauling on that rope for all I was worth to keep the whole rig from binding up.

Lesson number 12 of the day: It’s good to be the equipment driver. But it was down, he was safe and one of us was breathless with the effort. What followed was another snarling, swearing, grunting and snapping session as we pried and strong armed the auger back into place on the mounting plate. This time, as we lifted it slightly to engage the locking levers, Sean looked under the mounting plate from his seat and spotted the locking pins attached to those levers. Ah, now we knew! But we still hadn’t drilled a single hole and it was starting to get late.

Need overcame fear, and we bulled through those holes as though we actually knew what we were doing. We finished the last hole long after dark by the headlights on the skid steer with no further incidents. Sean drove it back down the hill while I trundled along behind with my armload of tools.

We put the equipment away and dragged ourselves back towards the house surrounded by a gentle breeze and the late-summer songs of frogs and locusts. “Well, we got it done,” I said to Sean, who followed behind me. There was a long pause and then he replied thoughtfully, “Yeah, maybe we don’t need to tell anyone how we got it done.” I laughed: “Agreed.”

The next day, the posts were set ahead of the rain and our first high tunnel was underway. We learned so much during that process, and throughout all the years since. But even though we seemed mismatched, both for each other and as farmers, we learned that if we did it together, we could “get it done.”

And that high tunnel stood firm and true, serving us well until May 2008, when we were hit by our first tornado. But that’s another story.

Jill runs Blue Gate Farm with her husband, Sean Skeehan. They steward 40 acres of family land in southern Marion County, Iowa, where they raise Certified Naturally Grown produce, laying hens, hay and alpacas, marketing through CSA and the Downtown Farmers’ Market in Des Moines.

Do you have ghosts at your place? Are you sure? We do.

Sometimes I’ll catch a glimpse. There are times when I think I feel them … but maybe it’s just my arthritis. Mostly, I know they’re here by signs they leave and things they do. I’ve always thought they’re the spirits of people who’ve gone before – those who’ve belonged to this farm, belonged to this land in their time. My ancestors, people who’ve worked here and maybe even our Indigenous predecessors.

There have even been times when I’m feeding our Brown Swiss calves and something about the way one looks at me, a quirk in her personality or a peculiarity in her behavior makes me feel sure that her great-grandmother, or maybe it’s her great-great-grandmother, is letting me know she’s here. Often, the spirits are more prevalent around the structures they left behind, the trees they planted, sometimes even the shape of the landscape.

I’ve had the extreme good fortune to farm on the Hardin County dairy of my childhood, land that has been in the family almost 125 years. I grew up with five brothers, helped take care of Brown Swiss cows and calves, helped raise the pigs that every farm had then, fed and rode a handful of horses and helped farm with the propane-powered Minneapolis Moline tractors favored by my late father. My wife, Beverly, returned to the farm to raise our family, just in time for the farm crisis, which eventually led us to PFI. But that’s another story.

I’ve spent most of my farming career working with Brown Swiss dairy, raising pigs to sell to Niman Ranch for more than 20 years and farming with some of the same yellow tractors – as well as their grey and silver descendants. It’s probably not surprising we have ghosts; it would be more surprising, maybe, if we didn’t. Just because we aren’t aware doesn’t mean they aren’t here. The real challenge is to recognize not only their presence, but their contributions – like when that old, rickety soft maple went over in the wind gust last summer and landed in the one place where it did the least damage. It’s tempting to think we got lucky. But is that what it really was?

Or there are the times I’ve been caught on the road in snowstorms and can’t see over the hood, can’t keep the windshield clear, can’t even see the side of the road, and somehow I get to my destination. It’s vainly tempting to think there was some skill involved. But was that really it at all?

And there have been untold careless and reckless shortcuts I’ve taken over the years – near misses, close-calls. It was always tempting to foolishly think I was cheating the fates. But was that really it?

Now, I know what you’re thinking. This guy has been in the magic mushrooms again; or he must really think we’re gullible; or if this is an allegory, he’s stretching the limits of his literary license. And I’d agree with you, if there hadn’t been times when the presence of an unseen force or an invisible helping hand was actually a more acceptable explanation than any of the others.

For instance, I used to like to keep the combine running as late as possible at night. There were times when, between the steady hum and rumble of the old Massey and the hypnotic flash of the stalks in the lights as they disappeared through the corn head, I’d start across the field and the next thing I knew, I’d snap alert just before I got to the other end, still on the row. Did I mention this was well before auto-steer? It was somehow comforting to think that, maybe, there was a co-pilot looking out for me.

And then there was the Mother’s Day night some years back when, as was my habit, I went to check one more time on a cow before I turned in. It was after the 10 o’clock TV news. Our dog Rose and I jumped in the old grey Dakota, windows down, for the mile-and-a-half trip up to the dairy farm, enjoying the night air. I parked by the milk house, slipped by the end of the bunk and picked my way gingerly across the 100 feet or so of concrete lot to the door of the cavernous dairy barn.

Now, I really should say a word or two about the barns on this farm. Dad had them built after we lost the original one in the 1960s. They are a testament to the way he thought things should be done. Four-foot-high solid concrete walls form the foundations; sizable, salvaged and long native-cut timbers provide the supports. There have been many times when I’ve been working in these barns and have caught myself looking up, almost like they are cathedrals; looking and remembering the amount of work that went in, and always amazed by the design, the craftsmanship, and remembering all the people involved in getting them built.

But on this particular spring night, those thoughts were furthest from my mind. But maybe they shouldn’t have been. I flipped on the light, ducked into the maternity pen and quickly realized the cow’s water had broken and she was in labor. I darted back to the milk house to grab the tools of the trade: a sleeve, obstetrical chains and hot water, thinking to myself, “with a little luck, this calf just needs some encouragement and I can get it born and nursing and make it to bed by a little after midnight.”

My hopes were quickly dashed when I began my exam, because all I felt was a tail. Now, if you’ve never had the privilege of helping deliver a calf, normal presentation is front feet first, with the head – nose first – cradled on the legs. Breach deliveries are not common, but the back feet have to come first. This calf had its legs underneath like it was laying down. That meant the calf had to be pushed back into the uterus out of the birth canal far enough so I could work the legs up one at a time.

As I reached in for the first leg, my “Oh shoot!” situation became “Oh (expletive deleted)!” because there were too many legs, too many feet. There was more than one calf. We had twins.

A whole bunch of mental calculations quickly went through my mind. Time is always of the essence with a calf delivery, doubly so with twins. In a difficult situation like this, time was even more critical. This was before the days of the ubiquitous cell phone, and I knew it would take 10 minutes to get to the milk house to get hold of the vet, and it would be another half-hour before he got here. I couldn’t wait for him, so I decided to go ahead and see, for a few minutes anyway, if I could do anything on my own.

Did I mention that helping deliver a calf has to be done one-handed? Oh, and it’s all by feel …and there’s no place for the word “tidy.” This is the kind of “gonna need clean clothes in the morning” kind of messy. In this case, I was pushing the breach forward, trying to pull a leg up before momma pushed him back, or the twin tried to sneak by. About the only description is one-armed juggling, (providing you’re doing it while up to your shoulder in the back of a cow).

The first leg was the hardest to get, but once the legs were up, the breach delivery came quite uneventfully. When the calf was in the straw, snorting and shaking his head to clear his airways, I quickly made sure the twin was delivered without issue. I don’t remember what time it was when I got headed home but I was relieved. I was thankful. And I remember thinking, “That’s two more souls among the living,”

In the hard light of morning, the relief of that reality and my gratitude met the gravity of the situation. This time it worked out, but that’s no guarantee about next time – because we know there will always be a next time. In a situation like this, when you’ve had some real accomplishment, it’s hard not to feel a little more confidence for the next time. But as I thought it over, I really had to wonder: Was I alone? I realized I probably didn’t save those calves alone. It was like with the combine: I had some help.

If there is a moral to this story, it probably has to be that we’re all never really alone if we’re open to the spirits around us – and that may have to be enough, for now, to always be open to the spirits because you never know when you may have to one-arm juggle.

John Gilbert farms with his wife, Beverly, and their family at Gibralter Farm, a 480-acre diversified operation near Iowa Falls, Iowa. The family raises Brown Swiss dairy cattle and pasture-farrowed pigs, along with corn, soybean, small grains and hay.

As a family, we read books out loud often to the kids. A favorite series was “Little House on the Prairie” by Laura Ingalls Wilder. When this story happened about 20 years ago, we were reading “The Long Winter.” Many of you have probably read those, and if you remember, they almost starved or died during the many blizzards. They even twisted hay together to burn to keep warm.

What impact it had on me, or us, I don’t know. But we’d had a snowstorm that filled our Iowa prairie farm with drifts and lots of snow. Most of our farm was flat with very little to stop the snow, but we had a three- or four-row grove on the north and west sides. Our farm was not very diverse back then. We farrowed-to-finished hogs, so we had to let sows out of their pens to eat each morning and night. We had a few sheep and chickens.

The barn was usually filled with hay, and many times that became the place to play for the kids. They created swings and tunnels that made me a bit anxious, but oh what fun they had.

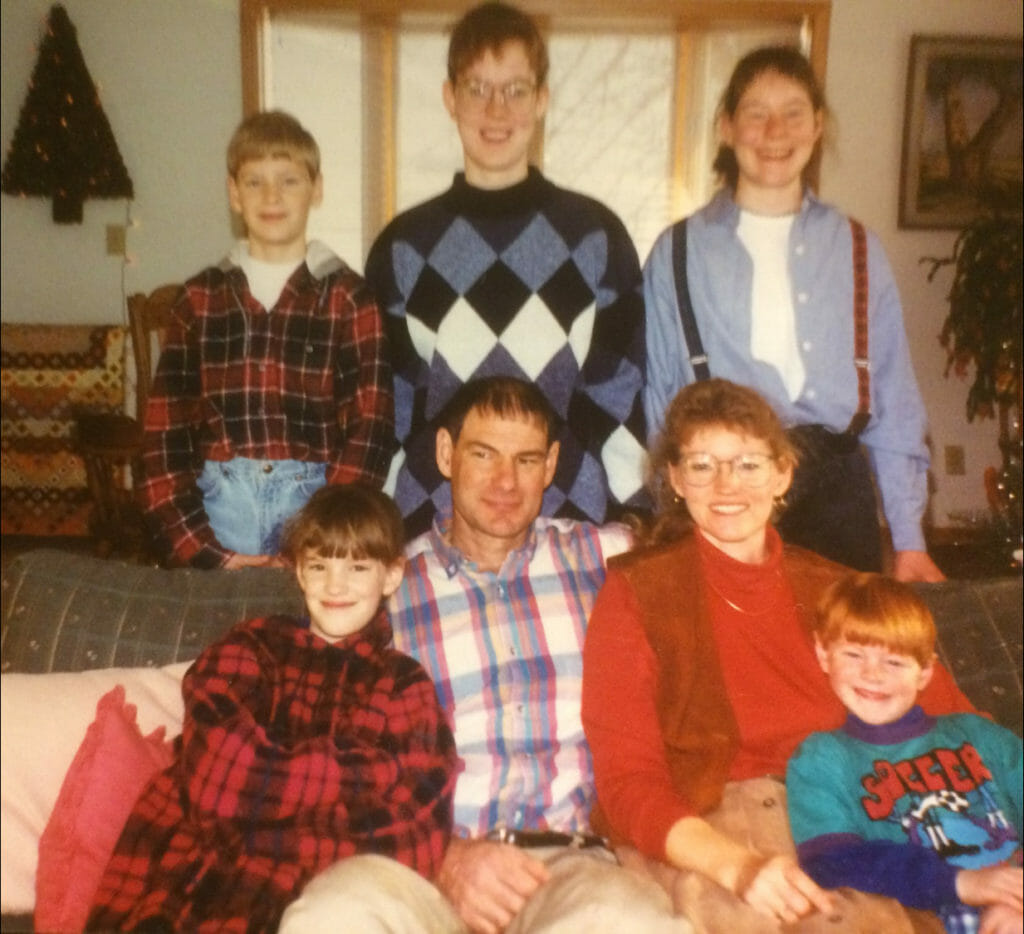

We had five kids by then: since we homeschooled, they were together a lot. I’m not a worrywart mom. I always sort of knew where they were, and sometimes I’d be out there with them. We had three daughters and two sons. Our son Torray was the oldest son, and he was fairly even-tempered, an easy-going kid.

With three older sisters, he was watched over – kept from trouble and told what to do. It wasn’t like him to be off by himself.

Like Torray, I too grew up on an Iowa farm. As a child, my three sisters and I were thrilled to get out in the snow to play. We made snow forts and snowmen, snowballs, laughing and giggling. My dad, a dairy farmer, would build huge piles of snow – we called them snow mountains – and he enjoyed watching us play. We would play outside until our faces were speckled with lots of freckles.

When you are a child, what does cold mean? Not much. After all, we had a black potbelly stove in our dining room growing up where Mom and Dad would burn coal and cobs to keep us warm. I remember Mom carrying out the ashes to the driveway. My own mom was not a worrier either, and she had several sayings, like, “It will all come out in the wash,” or “There will be a better day a-coming.” I’m always glad when I can remain calm. She just passed away in February 2020 at age 91. Thanks Mom.

My dairy farmer dad had little time to play, but he helped us make toboggan slides down those “snow mountains.” We used scoop shovels for sleds – just hook your feet on the neck and down you’d go.

Later, as I grew up, winters meant freezing cold and scooping snow until your arms hurt. Not quite so much fun. It was the end of the day of chores and subzero cold. So cold that your spit would freeze – although I never tried that. Your skin would freeze in seconds due to the windchill.

Whoever would want to be out there for very long? No one.

Like most farm homes at the end of the day, everyone would gather back inside to a warm, cozy kitchen and supper. Seven of us – five chattering, noisy kids. And so I assumed we were all in the house.

But soon we realized that Torray was not in the house. I tend not to worry, so just got busy making supper. A while passed and still no Torray. Where was he? My logical mind said, oh he’ll turn up soon.

I asked the other kids, but none of them knew where he was. Not at all like them to not know what he was doing last or tell him where they were going. I just thought he’d show up hungry.

But he didn’t.

This is when you really become an anxious parent. My anxiety was building. “Okay,” I said. “We have to go find him.”

Donning all our winter clothes again – scarves, mittens, boots and hats – we all became a search party.

Someone looked in the hay mound. He wasn’t there. Someone looked in the hog barn; he wasn’t there either. Someone even looked in the chicken house, because I had had a daughter get locked in there once. He wasn’t there either. We called out his name several times, listening carefully. No answer.

We even loudly rang the generational farm bell that came from Norway, gonging several times. This bell usually got everyone’s attention and you could probably hear it from miles away. The winter sky was gray and becoming increasingly dark, and the thermometer was dropping. A slight breeze was blowing. I didn’t want to be out there either. I don’t remember if we used flashlights, so we probably didn’t. No cell phone either.

We even loudly rang the generational farm bell that came from Norway, gonging several times. This bell usually got everyone’s attention and you could probably hear it from miles away. The winter sky was gray and becoming increasingly dark, and the thermometer was dropping. A slight breeze was blowing. I didn’t want to be out there either. I don’t remember if we used flashlights, so we probably didn’t. No cell phone either.

It was becoming a huge puzzlement and frustration. This was not a joke or funny now.

Where would a 10-year-old boy go? How could he just disappear? Was he lost? Was he lying somewhere injured? Your fears and imagination can kick in and go wild. I could almost see frozen fingers and skin.

It was one of those situations where you are almost holding your breath, and when the crisis is over, you let it out. Ever been there? Our eyes were straining in the dusk of the light, just trying to find some sign. Maybe a footprint or snow moved, or something.

Finally, after about what seemed like an endless search, older sister Robin shouted, “We found him!” Everyone hurried to the spot to be assured he was alive.

Our previous snowstorm had created a huge drift in the grove. He had scooped out a snow cave deep enough that he had not heard us or been aware of the darkness. The wind was making swishing noises that muffled our voices and the bell. He was snug as a bug in a rug in his cave, not even aware he was missing.

He had been right under our noses or feet.

I remember being in the snow caves. I remember bringing our dolls into those caves with not a bit of concern about being frozen.

I guess I had forgotten how insulating snow was when you are deep inside a snow drift. I never even thought he would be in a snow drift. What a wonderful feeling of relief it was to have a so-called crisis resolved. Dan and I both let out our held breath.

Needless to say, we were relieved and hurried inside to a warm kitchen and supper.

We all laughed about it while we were eating supper, but I think Torray knew we had been a bit afraid of frozen fingers and toes. I wasn’t really mad, just amazed at how deep he had made the cave. He had been so bent on his project, so absorbed by it, that the world outside didn’t exist. The power of creativity had captured him.

Just like in “The Long Winter,” we all survived. No one was lost in a snowstorm that year. No one froze to death or starved. We almost wanted to pick up the fiddle, like Pa when the train finally got the supplies through. But neither Dan nor I played the fiddle. As a mom, I was blessed to have a creative and safe son. I still do.

I believe we all have guardian angels, whether we believe in them or not. And we all have loving families that will go out in the cold to search for us.

Lorna Wilson farms near Paullina, Iowa, with her husband Dan and five adult children. The Wilsons raise organic corn, soybeans, hay and a variety of small grains on 660 acres at Seven W Farm. The operation also includes an organic dairy, a grass-fed beef herd, a sheep flock, pasture-raised broilers and laying hens and farrow-to-finish hogs.

Michael: I used to describe myself as an old bachelor who pounded nails for a living, but my joy in life was my U-pick strawberry farm out in the middle of nowhere. So when a couple young gals moved into the neighborhood, I hired them to pick strawberries and take them to market to sell.

Michael: I used to describe myself as an old bachelor who pounded nails for a living, but my joy in life was my U-pick strawberry farm out in the middle of nowhere. So when a couple young gals moved into the neighborhood, I hired them to pick strawberries and take them to market to sell.

One day, they both turned towards me and said, “Michael, you need to meet our mommy.” They told me about her gardening skills and said, “You really need to go over to her farm and see her gardens.” They were right: She had rows and rows of vegetables, and all of her gardens were surrounded by beautiful flowers. I could see that this was a woman who loved gardening as much as I enjoyed raising strawberries!

Darla: I come from a long line of gardeners. My grandparents on both sides of my family were fantastic gardeners. We never bought vegetables in the store, but we grew and harvested our own. I raised my five children on my garden produce. It just came naturally, so I assumed everyone knew how to grow and harvest vegetables, including my husband, Michael.

Michael: In 2010, we decided to get married. I started ripping strawberries out of beds, and Darla started planting vegetables … things I’d never heard of, let alone eaten. Well, we blended our talents together – Darla’s two green thumbs and my sleepless nights of searching YouTube, trying to find ways to better improve our soil. And slowly, our dreams started to come true.

Darla: It’s the end of a very successful growing season – we’re evaluating how we did, the things that went well and the things we want to change for next year, the things that made money and the things that didn’t. Tomatoes are our best seller, but green beans are close behind. In fact, we sell every green bean we take to market. We could even sell more, if we had them.

Michael: Darla, we need to raise more green beans!

Darla: What!? I’m the one that does the green bean picking! He’s not thinking about all the work that goes into picking green beans. I pretty much love everything there is about gardening, except for two things – one is picking weeds out of carrots and the other is picking green beans. But I do them both.

When it’s time to pick green beans, it’s usually the middle of July, 95 degrees in the shade, not a whisper of a breeze. You can just see the heat waves shimmering on the horizon, and you can smell the sun baking the prairie grasses beside the garden. The sweat is running into and stinging my eyes, the mosquitoes are buzzing around my ears and the gnats are crawling up my nose.

The bean leaves itch my arms, not to mention the endless back-breaking bending over. “Absolutely not, Michael!” I declare. “I don’t care how many green beans you can sell at market, I draw the line there. I cannot pick any more green beans!”

Michael: Being the dreamer that I am, I was lost in thoughts of doubling our profits on green beans, so I missed that little part about the hard work. “Darla, I have the answer to the problem,” I exclaim. “Next season, I will help you pick those extra green beans!”

Darla: I am really doubtful, but I go along with his plan. It’s the next summer. Middle of July, 95 degrees in the shade, not a whisper of a breeze. You can see the heat waves shimmering on the horizon. Guess what? Time to pick green beans!

I gather up some 5-gallon buckets, and then I go looking for Michael. “Time to pick green beans, Michael,” I say. He looks confused, but then a light comes on. I’m sure he was hoping I’d forget about his offer to help me pick green beans, but he meekly follows me out to the garden – specifically, that extra 70-foot double row of green beans that he wanted us to plant. I grab a bucket and give one to Michael. The sooner we get started, the sooner this job will be over. But hey, it shouldn’t be so bad this time with Michael’s help.

I bend down and start picking at the end of one row, and Michael starts on the row right beside me. The sweat that was on my forehead is now running into my eyes and blurring my vision, the mosquitoes are buzzing around my ears and the gnats are starting to crawl up my nose. The fuzz on the bean leaves is itching my arms and my back is starting to moan. We work in silence. All you can hear is the steady plunk, plunk, plunk of beans in the bucket. You can’t hear the sweat that’s now dripping off my chin as it hits the dirt. Plunk, plunk, plunk.

Wait a minute. Suddenly, it dawns on me: I’m only hearing that plunking coming from my bucket. I look over at Michael. While I’m several feet down the row, he’s still at the beginning of his. There must be some explanation for this! He’s the brains of this operation – it’s not rocket science. Just grab the beans and throw them in the bucket. The faster we go, the sooner this job is over. “How’re you doing, Michael?” I ask.

Michael: Darla just took off down the row. Didn’t bother to explain how to size the beans. So I’m down on my hands and knees, looking at each one and trying to decide whether it’s big enough to pick. I sigh and think, “Wow. I didn’t know it could be this much work!” Strawberries are a lot easier to pick. You know the green ones aren’t ready, and the ones turning orange will be another day or two and those red ones, they’re ripe right now. And the ones that squish in your fingers, you throw them into the air and Hershey, our chocolate Lab, would always catch them. I sigh again: She’s halfway down the row already. She must not be finding many beans either. “Darla, you know what? I don’t think I’ve ever picked beans before.”

Darla: I knew it! It was just too good to be true. He does all this research, all this studying, and he doesn’t know how to pick green beans. I continue down my 70-foot row, trying to ignore the mosquito stings on my arms and my now-screaming back. I get one bucket full and reach for my second. I glance over at Michael: He’s still only a few feet down his row. I grumble with each breath of hot summer air. I can smell the sun baking the prairie grasses beside the garden. It smells like fresh bread, but I’m not hungry – only really thirsty. But if I go in for a tall glass of cold ice water now, I’m not going to want to come back out. So I keep on going, down my 70-foot row. Plunk, plunk, plunk.

I get to the end, do a 180 and start down Michael’s row. I am resigning myself to this bean-picking fate. I get my second bucket full and I’m only a few feet away from Michael. I look over in his first bucket: It’s only half full. I shake my head and say, “I’ll finish picking beans, Michael, go ahead. You can do something else.” Whoa! He was up and out of there in no time. He can sure move fast now! I take his bucket and go over the part of the row that he’d supposedly picked. I end up finding enough green beans that he left to fill the bucket. I don’t think he’s going to offer to help me pick green beans again!

I am just going to have to figure out how to pick them more efficiently, and let Michael keep doing all those other things he does so much better than me. We still do make a pretty good team!

Michael: From this experience, one might see how well we work together. You know, we’re not two peas in a pod; we are not even two pods on the same bush. Actually, she’s the green bean and I’m the plump strawberry, and somehow we ended up on the same farm. Even though it sounds kind of funny, we end up making it work. I dream of tomorrow and Darla carries us through the day.

Darla and Michael Eeten began GoodEetens Produce Farm in 2009. They grow fruits and vegetables at their two farm locations, which include 12 acres near Everly, Iowa, and another 1.5 acres near Boyden, Iowa. Darla and Michael sell their produce through a CSA and at farmers markets.

I want to tell you a story, but I’m not sure where the story begins when everything I see is a circle. The human experience is continually flowing rather than having concrete beginnings and endings. Yet perhaps there are defining moments in our lives that are natural places to begin when sharing our stories. Imagine, it had probably been 140 years since a bison calf was born on our property as part of a family herd, and it was not at all what I expected.

Perhaps the story began following high school when I left for the U.S. Navy, following in the footsteps of my father and my brother. After military service, I traveled the world, pursued my higher education and continued to experience other cultures and other ways of knowing that were very different from the culture in which I was raised. Seventeen years later, I returned to Iowa to the home and culture where I grew up.

Today, I feel fortunate to be able to help restore native prairie, oak savanna and other native ecosystems on our 180-acre farm just northeast of Ames, Iowa. Ultimately, we are working to create an ecosystem as rich and biodiverse as possible with the management of a bison family herd.

I’m not entirely certain where the idea of raising bison came from. I think back to an early part of my childhood and a fascination with the keystone species; maybe that my father raised bison for a short period of time; or even spending time deep in the Amazon rainforest in South America, where I worked with a traditional healer who was restoring native plants for his healing center, which was inspiring to me.

Spending time with traditional healers in Peru sharpened my senses about Indigenous ways of knowing and the relationship to our environment. Through relations made in South Dakota among Native American people, I gained a deeper understanding of bison and their role within the ecosystems of the northern Plains. My relatives helped relocate the bison herd to our farm: We made prayers and sang them in with traditional songs. Today, I cannot see the bison as separate from the land – they are essential to our restoration efforts on our farm.

Imprinted on the land

It must have been early spring because there was a morning chill in the air. I remember clearly movement, changes in the season that bring a smell of the earth and new growth. The bison had only arrived at our farm a few months earlier, so they were still in the winter holding area, which is about a 12-acre closed-off area.

Normally, bison would have roamed thousands of acres, and they can even survive some of the most extreme winter months on their own. It’s the reason they have that big hump above their shoulders, that muscle for moving the deep snow out of the way to access grasses. I once slept outside under a bison robe in the middle of a South Dakota winter on top of Spirit Mound. But even in the summer heat, they are so well adapted they don’t need to hang out in the waterways to cool off, like other livestock.

Even though I believe bison are remarkable and self-sustainable, we have limited pasture available. So we roll out bales of hay for them during the winter months or until we release them to the pasture. We try to do things as naturally as possible, but recognize we have limitations.

As I shared at the start of this story, it was meaningful to see what I thought was the first bison calf of the season, an emergence of new life and unfolding of something bigger than ourselves. It was exciting. I imagined the last time this land had seen a bison calf being born in this way; that the calf would be imprinted on the land. I took it all in. I watched it with its mother and how the members of the herd interacted with the newborn.

I realize now how much I’ve learned and what a profound privilege it has been to experience the bison, and how, in such a short period of time, they have already begun to change our landscape for the better. The way they rub on the young cedar trees, helping to open up the prairies; or the way they wallow, creating potholes for birds and other native animals to drink after a rain. The bison have taught us so much over the years, but I didn’t really have much experience with them early on – and certainly, raising them in the way that we have, the bison themselves have been our best teachers.

Born of the earth

I had rolled the bale of hay on the far side of the winter holding area down a hill and returned home to grab my camera so that I could document the moment. As I was making my way back out to the far part of the holding area on the four-wheeler, I was surprised to see four bison on their own. It seemed a little bit out of place and I wondered to myself why they weren’t with the main herd. It’s not uncommon to see a bull group break off from the main herd. Realizing that wasn’t the case, I approached them and nudged them to move along.

Bison make this low guttural grunt at times when calling to each other, but I hadn’t been around bison long enough to identify the meaning of their sounds. I heard a “grunt, grunt.” I nudged them a little more and encouraged them to move along. We never like to pressure the bison, so I took my time. After a little coaxing, all of them left – with the exception of one. For whatever reason, he did not want to leave. I later came to understand this was a younger bull, most likely an uncle. After one last push, the last one finally left to join the main herd. It was just curious to me and made me pause. I looked around the area.

There’s about 6 inches of space between the bottom of the woven wire fence and the ground. On the other side was a 12-inch hole where a telephone pole must have been. I’m not really certain I can describe what I was feeling. Something just wasn’t right; maybe it was intuition. I climbed over the fence and looked inside the hole – there was a calf just staring up at me.

Its head was just perfectly below the level of the ground. I mean, if I wasn’t looking directly over it, there’s no way I would have seen it. And the image is still incredible for me to think about. There’s this head and it’s just emerging from within this perfectly round hole, new life emerging from the earth. It blew my mind that I could have so easily missed that calf.

Bonded by the family unit

I immediately telephoned my father. Not knowing how to explain this situation over the phone, I simply gave him my location and told him, “I need your help with a calf as soon as you can get here.” It didn’t surprise me that it took him very little time to get to me – but before he arrived, the image of that bison calf was so deeply powerful, I snapped a quick photo.

Coming from the military, members of my family are often quick to assess difficult situations and problem-solve. Beyond that, I’ve certainly learned a lot from my father, and really none of this would have even been possible without his belief in my vision and, ultimately, a desire to leave a legacy for future generations. But I can remember in the moment, when we were getting ready to pull the calf from the hole, he said, “Jathan, you’re going to need to bottle-feed it because it has been separated from its mother.”

I wasn’t certain what the outcome would be, but we raise our bison differently than a typical cow-calf operation, and we place high value on the family unit. I would later come to understand that even though the mother had moved along, that young uncle refused to leave his nephew. It was enough to let me know something wasn’t right.

“I just need your help to get the calf out of the hole,” I told my father. “We don’t know what will happen. That herd instinct is strong.” I also recognize this sort of tension between my father and me about how best to care for the bison – or maybe it’s my desire to create space to allow things to unfold more naturally.

I remember an argument with my father when putting in fence line. I recall him being so set on putting in a single gate, while I was leaning towards multiple gates. My father is wise and I imagine he was basing his decision on experience, and perhaps even costs. But he also mentioned that having one gate would train the bison to use it. But I didn’t want to train the bison, so we eventually put in two gates and allow the bison the freedom to choose.

United in a circle of life

I climbed back over the fence and my father helped me slip the calf back under the woven wire. Bison calves are strong when they are born, but the calf didn’t fight me. I carried it in my arms – this heavy, muscular, orange-colored, beautiful animal – up towards where I had rolled out a bale of hay. The bison were just on the other side of the hill, so they couldn’t see me and I couldn’t see them. I called to them and one came in view just over the hill.

I put down the calf and backed away. I was hopeful, not knowing what I’d do if it didn’t work. It took a moment, but then I heard some grunts and that mother came over the hill and ran up to her calf. Bison have a remarkable sense of smell, and she nudged it with her nose. The calf followed its mother back to the main herd. The bison calf survived, but it was more than that to me.

It was a validation that the way in which we were raising them was meaningful. And the experience has framed our understanding of our farm from the beginning. In fact, the image of the bison emerging from the earth within a circle became our logo for Native Prairie Bison. But importantly, it became a metaphor of something bigger than ourselves.

It’s certainly not always easy to do things differently, but we trust in the bison. By remaining committed to cooperating with the native species on our farm, we continue to learn in unexpected ways. The story of the calf in the hole is one we’ve kept returning to – the idea that we can learn from and trust in the bison; and when we provide them the freedom and space to be bison, like other native species, new life emerges.

Jathan Chicoine, his wife, Racheal Ruble, and family own and operate Native Prairie Bison in Story County, Iowa, where they raise 100% grass-fed bison and work to restore native Iowa ecosystems. Jathan is also a program manager at Home Base Iowa, a public-private partnership supporting veterans, military personnel and family members in Iowa.