A Practice in Faith

Arlyn and Sue Kauffman are living out their faith through farm, family and community.

Arlyn and Sue Kauffman had skunk troubles. It was a crisp autumn day, but all the windows and doors of their century-old farmhouse were open in an effort to cleanse the air.

The night before, a skunk had found her way into the crawl space under the house. Though Arlyn and Sue hadn’t seen the olfactory offender, they could smell her telltale perfume.

As the wind wafted in, drying corn whispered in the field across the road. Bright shadows of maple leaves danced in the front yard as the wind whisked away the lingering scent.

Arlyn grew up on these 240 acres of Green Ridge Family Farm, near Weldon, Iowa – but a skunk under the house was a first for him. Still, while others might be vexed by such a malodorous guest, Arlyn understood and accepted the reality with grace.

Though he was nonplussed, he saw skunks as simply part of the wider community of life on the farm. Twice, Arlyn has released skunks from live traps caught elsewhere on the farm and used the acts as teaching moments for his children.

“I want the farm . . . to be a place where they learn to nurture, not dominate and exploit,” Arlyn says of the ethos he wants to pass to his children.

For Arlyn and Sue, farming is an act of stewardship. Skunks, for instance, help control rodent populations – important when eggs and grain are the backbone of the farm.

Arlyn believes his family’s job is to simply care for the land for the time they have. And that care extends to the communities the land supports, be it the customers who buy their eggs – or the skunks who eat the mice (and fumigate the house).

This belief is firmly rooted in Arlyn and Sue’s Mennonite faith, which underpins how they live their lives. “We believe that the Earth was created by God, and Jesus gave us the example of nurture and care, not exploitation,” Arlyn says. “We want to follow that as best we can.”

Farmers in Fellowship

If Arlyn’s Mennonite faith is the river that carries him through life, community is the current flowing under the surface. Arlyn explained why in closing remarks he gave at the 2018 Cooperators’ Meeting, PFI’s annual gathering of on-farm research participants. Amish Mennonites, he said, believe that “the smallest unit of sustainable spiritual life is not the individual, but rather the group.”

“So,” he continued, “it’s in my psyche. I can’t not think like that.”

As fields get bigger and farms spread farther apart, farming is becoming lonelier for many farmers. There’s less opportunity to chat with a neighbor at the fence line. And as livestock leave the landscape, there are fewer fence lines to meet at.

But for Arlyn, such a reality would be unbearable. Cooperating with neighbors and family, exchanging time and equipment – generally helping each other – sustains him. “If I had to do this all by myself and everyone else in the area was a competitor – and I know that’s how some farmers feel – I don’t think I could do it,” Arlyn says. “It would destroy me.”

Luckily, Arlyn doesn’t have to worry about a quiet and lonely struggle. Beyond the shared ethic of mutual support within his community, he also has neighbors using similar production practices.

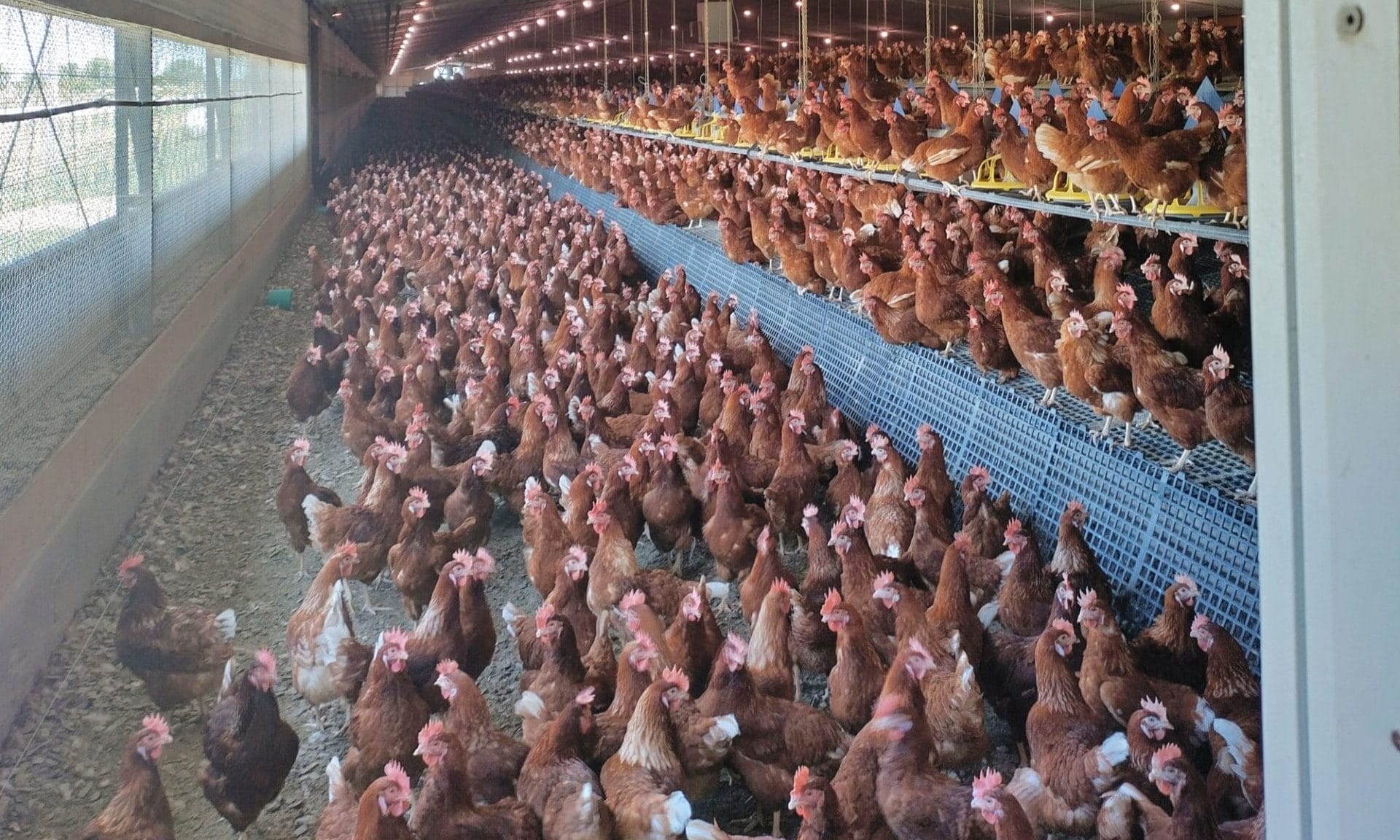

Eggs are a mainstay at Green Ridge Family Farm, which Arlyn and his family source from about 20,000 cage-free hens housed in a 500-foot-long barn. To feed that many birds, the Kauffmans raise their own non-GMO corn, oats, barley, soybeans and wheat. The hens also have daily access to 50 acres of permanent pasture. This system lets them market their eggs with specialty certifications, including pasture-raised, GMO-free and American Humane Certified.

In their church, four other farmers raise eggs this way, and market and distribute those eggs through the same company as Arlyn and Sue – Fairfield Specialty Egg, based in Illinois. The company’s business model, Arlyn says, prioritizes helping young farmers gain access to agriculture.

Each family is allowed one barn, which spreads opportunity more widely within the Mennonite community. When a new family is starting off, those who already have chickens lend support, from physically building the barn to sharing knowledge and experience. The Kauffmans have been raising chickens since 2015 – so they now often mentor beginners in their community.

“It’s a lot of collaboration,” Arlyn says. “There’s a lot of phone calls.” They also get asked about their chickens during church meetings, though Arlyn emphasizes they try not to do that too much.

Within their close-knit community, however, Arlyn’s family has also received its share of support. Once, he recounts, he found himself in a predicament. It was haying time, but he was called away unexpectedly. He knew he’d have time to cut the hay, but not to bale it. The weather forecast didn’t look good, so Arlyn asked his cousin for advice. Should he take the chance and cut, potentially leaving cut hay in the field to rot in the rain, or hope the weather held out until after he returned? “It’s time to mow the hay,” his cousin replied. “Go mow the hay. We’ll make sure it gets baled.”

These acts of mutual aid are recorded in a book, Sue explains. When you help move cattle, or someone loans a planter, it all gets written down. At least once a year, she tallies it all up. Debts are settled. But more often, the exchanges have been so equitable that hosting someone for dinner is enough to balance the accounts.

This ethic of community care is a core value. But, careful not to misrepresent, Arlyn says it doesn’t mean he and Sue are immune to economic realities.

“We feel the pressures to try to chase the bottom line,” he says. “But I feel like by working together, we can help each other resist those pressures.”

Good Works and Grace

At 20,000 hens, the Kauffmans’ flock isn’t small. By national standards, however, it’s not huge. According to The Poultry Site, egg operations with 75,000 or more hens account for 95% of all layers in the U.S. Commercial in-line facilities, where eggs are laid and processed at the same site, account for 85% of all table eggs in the country. These farms can have up to 6 million layers, with each poultry building housing anywhere from 50,000 to 350,000 hens.

Still, Arlyn describes his operation as “commodity eggs with specialty certifications.” The eggs leave the farm, go through intermediaries and end up in California. “I’m not sure I feel good about that from a social standpoint,” he says.

That his eggs don’t serve his local community bothers him, and he grapples with the ways his management doesn’t fully reflect his goals of stewardship and community. When asked what his biggest challenges are, Arlyn sits for a time in contemplative silence, scratching the ears of the dog by his side. “I think for me, it is a philosophical dilemma.”

Sue agrees. “We believe that we – you, us – were created to take care of the Earth and to be productive.” Part of that mandate of their faith, Sue explains, is making sure everyone has a chance to connect with the food they eat. “Sometimes it feels like what we’re doing, even though it’s maybe not as bad as, you know, the mega conglomerates, it’s not helping that challenge.”

The dilemma for them is palpable. But Arlyn says it’s a tradeoff. Sacrificing community with their customers has let them live out other core values. “It has given us the opportunity to be on the farm with our children. And it provides enough income to pay for itself, for our farmland loan and to buy machinery,” he says. “It allows us to be here and be a part of the ag community.”

The nest boxes are angled so that the eggs roll onto the conveyor belt where Arlyn watches for any defects.

The work itself is also a family endeavor, which is just as important to them. “It brings me joy to work with my children,” Sue says. Farming together has engendered many meaningful moments. She describes how her boys used to roller-skate around the egg room, and recalls watching them “walking a little straighter because they are contributing to something that needs to be done.”

“I also enjoy helping with the birds sometimes, and with the eggs,” Sue adds. “But I like the working together – doing things together as a family and an extended family.”

The Narrow Gate and the Difficult Way

As Arlyn and Sue look to the future, their vision is one of more connection to land and community, and contentment. Arlyn dreams of a mobile pasture system for his chickens so he can use them and other animals to harvest forage, and to continue improving soil health.

Arlyn and Sue also hope their children can take the next steps on the path of community connection and care. Both agree they’d want their children, should they pursue agriculture, to farm smaller, not bigger, and in a way that directly serves their local community.

“Moving in that direction means scaling down a lot, which then makes cash flow challenging,” Arlyn says. “But I do want them to have a sense of responsibility in taking care of the Earth.”

“It’s part of this personal journey that I have been on to not make efficiency the God,” he continues, “to not make the bottom line of cash be what drives our lives.”

Systemic forces are powerful, however, and Arlyn acknowledges the impact of growing up in a system that prioritizes financial return in exchange for work. “I hope my children can do better with that [dilemma] than I have,” Arlyn says, “that they will be able to make choices based on the greater good.”

Learn More

Listen to Arlyn’s closing remarks at PFI’s 2018 Cooperators’ Meeting, where he shares more about how his faith underpins his life and his farming practices.

Read “A Mennonite’s View of Grace” by Thomas R. Yoder Neufeld.