The Gift of Presence

By practicing the art of observation, two farmers solve a practical challenge while improving the lives of their animals.

There is an art to noticing.

Whether it’s spying the subtle or seemingly mundane details of daily life – the old spiderweb in the corner of the hayloft; the way fallen leaves gather in the yard – or the bigger patterns that unfold over time, observing is a way know someone or something more deeply.

In farming, as in other areas of life, the art of paying attention highlights need – which incites creativity, which begets renewed observation and further impetus to create. This cycle of slow iterations of watching, followed by trial and error, helps us improve our lives, ourselves and our farms.

For Kevin Martin and Heidi Eger, this art of noticing is both practical and intrinsic – a way of improving, and of giving to the animals they care for. Both have created different styles of mineral feeders after carefully observing the needs of their animals and their farms. But the end products weren’t simple one-and-done projects. The solutions they found to a vexing farming challenge were the result of continuously watching, adjusting, innovating, paying attention and tweaking.

Observation as Offering

Kevin Martin’s goats in the pasture, where native perennials are rebounding on his farm near Mount Ayr, Iowa.

For Kevin, the art of noticing is closely linked to being present. “What we can do as people is offer ourselves. That’s all we can offer,” Kevin says emphatically, his resonant baritone carrying over the breeze this autumn day at Holdfast Farmstead in Mount Ayr, Iowa. “And our main thing to work with is attention – going out with the animals in the landscape. It’s immersion, knowledge and offering.”

Kevin has been sharing his journey from growing up in Missouri to Amazonian naturalist to ship captain to audio book narrator and Iowa goat farmer (he and his family raise Kiko goats, St. Croix-Katadhin sheep and pasture-raised duck and chicken eggs). The through line? “Just chasing life, finding where life is.” The farm offers his family their biggest adventure yet, he says. “The amount of life and diversity and what wants to be tallgrass prairie is incredible. There’s a lot of room to pursue life very viscerally.”

But to work with that abundance, he’s had to learn to understand it. When he first started to farm, he says he didn’t see everything that he now sees in his pasture. “It just wasn’t there for me. There were so many things to pay attention to.” With the help of friends and mentors, and spending time with his animals, Kevin has gained confidence to better understand what he’s seeing.

One of the ways this practice of paying attention has manifested on the farm is in the mineral feeders Kevin has been developing. He wanted buffet-style feeders so livestock could choose the specific minerals they want to consume, rather than eating a mineral mix with predetermined mineral ratios. The feeders went through three iterations before Kevin was satisfied.

The first mineral feeder he bought was actually designed for cattle and proved too big to be useful. The goats couldn’t reach into it easily, and it was far too heavy to move with his herd.

Kevin built a second feeder setup, making it smaller for goats and light enough that he could move it by hand. But there were still a few problems with the design. The joinery in some key spots wasn’t as sturdy as he’d have liked, and the goats loved to stand on the rubber rain flap, preventing others from eating.

Kevin points out the rubber lid on a early mineral feeder design. Though weatherproof, the goats liked to stand on it too much.

These observations led Kevin to make changes in the next design. He strengthened the weak joints and removed the rubber flap, opting instead for a marine-grade plywood awning. The new setup is tall enough for Kevin’s goats to fit their heads to eat, but too short to clamber into. Now, the goats can leap onto the mineral feeder’s roof to their hearts’ content without impeding their peers. He’s already seen an increase in consumption.

But Kevin isn’t done with his mineral feeder observations. It’s not yet clear how the goats’ mineral intake changes seasonally, and around the pasture. This past year, Kevin has been experimenting by only giving mineral when the goats are eating hay. His hope is that this pushes them to eat more diverse plants when they’re on pasture to get what they need.

“There are so many variables, it’s difficult to say for certain,” Kevin says. “But I think that they’re eating further into the weeds.” Since starting this practice, he has reported seeing new patches of prairie grasses popping up through the pasture – a sign that something seems to be working.

As he waits to bring the mineral back out to the goats, Kevin is already thinking about adaptations for the next version. He wants to better exclude moisture, since the roof doesn’t provide as much protection as the rubber cover. But he enjoys this brainstorming process.

“Tinkering on projects, and being out in the pasture, just noticing and coexisting – that’s probably my favorite thing.”

Many Little Tweaks

Near Canton, Minnesota, Heidi Eger watches her sheep grazing amidst the mountain range of mole hills at Radicle Heart Farm. These mounds of dirt pose problems for how she moves her shade structure, but she’s overcome them by incorporating a winch into her design.

Heidi Eger shows how quickly her shade structure can be disassembled for winter on her farm near Canton, Minnesota.

It only took four iterations to find a shade design she’s happy with. Her mineral feeders, for mixed minerals rather than buffet-style, have been a tougher nut to crack. “There have been so many little tweaks,” Heidi says. “I’d recognize, ‘All right, they need something else, but I don’t know what it is.’”

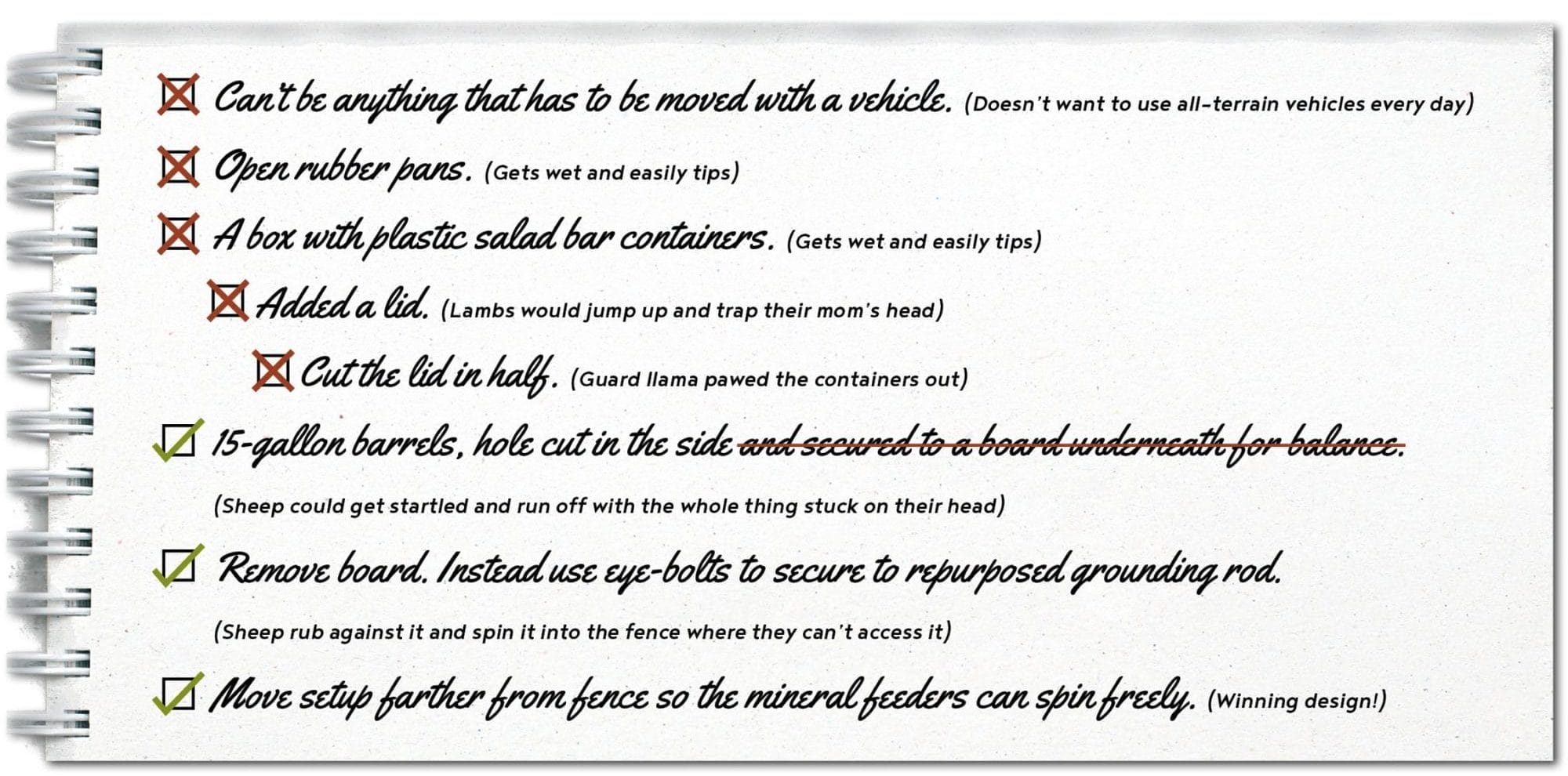

Finding a design that worked took years. Here’s an abbreviated list of Heidi’s ideas and attempts:

The improved design also led to important observations about her animals. Previously, Heidi had no reliable way of tracking how much mineral the sheep were getting and how much was ending up wasted on the ground. Now that it was all staying in the bucket, she found herself putting out 3-4 cups of mineral every day for two full weeks. Her 40 lambs “were going crazy,” Heidi says. “I felt really bad. I was like, ‘Oh, I’ve been that dramatically not giving you what you need.’” But mineral consumption has slowed down and regulated as the sheep have balanced their deficiencies. “I am really excited to pay more attention to how their intake changes over the season, because I have never been able to consistently before.”

This new horizon of observation wouldn’t be possible without Heidi’s careful watching and willingness to test new approaches. That kind of sustained, patient attention is a gift: By finding a mineral feeder design that works for her sheep, she’s better able to provide them what they need, when they need it.

But this design, too, isn’t final: Heidi is already thinking about potential future adaptions. “I think you could do this and make it buffet style,” Heidi says, musing out loud whether little containers might work. “Buffet minerals are something that’s very interesting to me. But I need to be able to consistently give them the easy mix for a couple years before I get fancy.”

For now, Heidi is satisfied to watch her meticulous labor pay off.

“To have something that actually works is very exciting, after many years of many, many failed attempts.”

Luckily, she adds, she didn’t spend much money on those iterations – she had repurposed materials from elsewhere.

Phil Specht, longtime PFI member and farmer outside of McGregor, Iowa, once said that you’ll recognize the grass is ready to graze when it “waves, beckoning the cows to eat.” It’s the type of deep, poetic knowledge that comes from a mindset (and in his case, a lifetime) of giving attention and knowing the land.

With so much calling for our focus all the time, seeking to divide our attention, the act of noticing is a gift – one that enriches both observer and observed. It’s both an art, and a choice. For Kevin and Heidi, that choice is rooted in a desire to understand at a deeper level how they can better serve their farms.

“It’s misleading but tempting to assume that it’s all about exercising control,” Kevin says. “It’s about co-participation, about being present.” As he speaks, he watches the grass wave, beckoning the goats to pasture.