In a Nutshell:

- Sam Ose has been struggling with weed control in seed corn. He wondered if interseeding a cereal rye cover crop might help suppress weeds and tested two seeding dates: when the corn reached the V6 stage and a month later after the male rows were eliminated.

- Ose hypothesized that interseeding cereal rye at the V6 stage would produce more biomass and weed suppression than interseeding after the male rows were eliminated; and that interseeding a cereal rye cover crop (on either date) would not reduce seed corn yield compared to the control (no cover crop).

Key Findings:

- Interseeding the cereal rye cover crop at V6 (July 1) resulted in nearly three times as much biomass compared to interseeding after the male rows were eliminated (Aug. 6).

- Ose did not observe any less weed pressure in the cover crop strips (either interseeding date) compared to the no-cover-crop control strips.

- Seed corn yield was not affected by the cover crop (interseeded on either date).

Methods

Design

Ose planted seed corn on May 15, 2019 at a population of 35,000 seeds/ac to a field that was planted to soybeans the previous year. One month prior, on Apr. 15, he applied 130 lb N/ac as anhydrous ammonia. For weed control, Ose cultivated the field on June 16, applied Laudis at a rate of 3 oz/ac on June 20 and cultivated again on July 1.

To test whether interseeding a cover crop could improve weed control in seed corn, Ose compared three treatments:

- Cereal rye interseeded at the V6 corn stage (July 1);

- Cereal rye interseeded after male row destruction (Aug. 6);

- No cover crop (control).

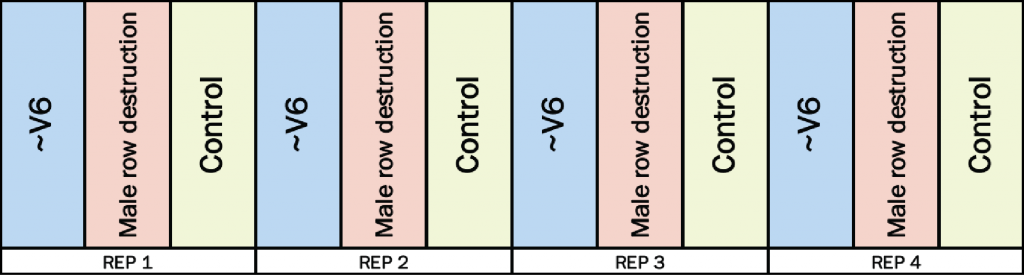

Ose implemented four replications of each of the three treatments in strips that measured 25 ft wide and 625 ft long (Figure A1). For both seeding dates, he interseeded the cereal rye at a rate of 70 lb/ac using a seed spreader mounted to the back of a four-wheeler.

Measurements

Just prior to seed corn harvest, Ose clipped samples of aboveground cereal rye growth (stems and leaves) from each of the strips containing cover crops on Sept. 3. We determined the amount of cover crop biomass by weighing the samples after air-drying for four weeks.

Ose assessed weed pressure by traveling down the former male row in the center of each strip on a four-wheeler on Sept. 3 and counting each waterhemp plant that was taller than the front of his four-wheeler.

On Sept. 5 and 6, Ose harvested the seed corn and recorded yields from each individual strip.

Data analysis

To evaluate any differences among the treatments Ose tested, we calculated the least significant difference (LSD) for each measurement: cover crop biomass, waterhemp count and seed corn yield. If the difference between any two treatments is greater than the LSD, the difference is considered statistically significant. For this trial the LSD was calculated at the 90% confidence level. In other words: A statistically significant difference between treatments is one that probably did not occur by chance 90 times out of 100. We can make these statistical calculations because Ose’s experimental design employed the principle of replication (Figure A1).

Results and Discussion

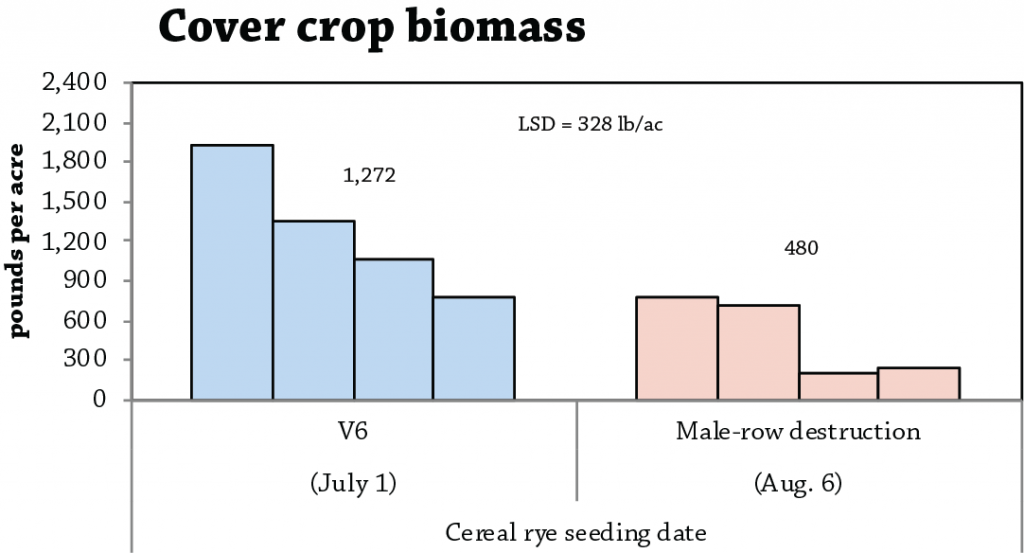

Cover crop biomass

Interseeding date had a statistically significant effect on the amount of cover crop biomass produced. The cereal rye interseeded on July 1 produced nearly three times as much biomass as the cereal rye interseeded on Aug. 6 (Figure 1). These results mirror those of fellow cooperator Jack Boyer’s – in a 2015 trial, Boyer observed more cover crop growth the earlier he interseeded to standing seed corn.[1]

Figure 1. Cereal rye cover crop biomass at Sam Ose’s on Sept. 3, 2019. Columns represent biomass readings for each individual strip. Above each set of columns is the mean for both cover crop interseeding dates. Because the difference between the two means is greater than the least significant difference (LSD), the treatments are considered statistically different at the 90% confidence level.

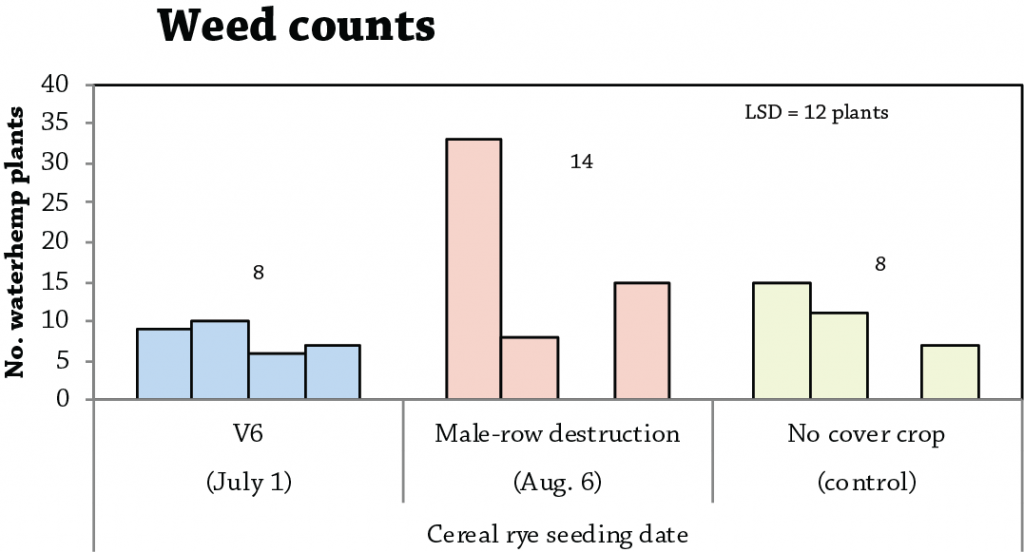

Weed counts

Interseeding the cover crop at either date had no effect on the number of waterhemp plants Ose counted in the treatment strips (Figure 2). As to other weed species present, Ose noted: “Fall panicum and foxtail species germinated early in the season before I interseeded any cereal rye. Those grass weeds acted somewhat as an unplanned cover crop that suppressed broadleaf weed growth. Being chemically-sensitive seed corn, we couldn’t use glyphosate to kill the grasses before interseeding the cereal rye.”

Figure 2. Number of waterhemp plants counted through the middle of each strip at Sam Ose’s on Sept. 3, 2019. Columns represent waterhemp counts for each individual strip. Above each set of columns is the treatment mean. Because the difference between any two means is less than the least significant difference (LSD), the treatments are considered statistically similar at the 90% confidence level.

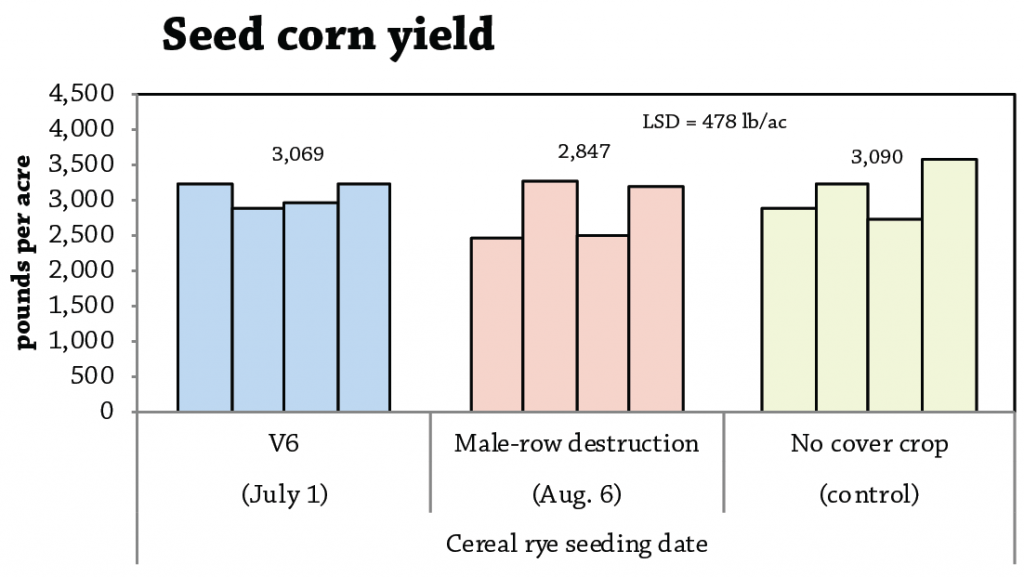

Seed corn yield

Ose detected no differences in seed corn yield among the three treatments (Figure 3). Jack Boyer’s experiment in 2016 found similar results.[2]

Figure 3. Seed corn yield at Sam Ose’s in 2019. Columns represent seed corn yields for each individual strip. Above each set of columns is the treatment mean. Because the difference between any two means is less than the least significant difference (LSD), the treatments are considered statistically similar at the 90% confidence level.

Conclusions and Next Steps

Ose was pleased that interseeding a cereal rye cover crop at either date had no ill-effect on seed corn yield, which is what he suspected to happen. Interseeding a cover crop in late June or early July, as Ose did in this study, appeals to farmers because it can be accomplished without specialized equipment and because it does not interfere with other management practices like harvesting a cash crop in the fall. Seed corn acres are prime candidates for interseeding because of the seed corn production process. The elimination of the male row and detasseling of the female rows in mid-summer permits ample amounts of sunlight to reach the soil surface. A cover crop can thrive on this sunlight whereas cover crops interseeded to field corn run the risk of being shaded out when the corn grows tall and closes the canopy by July (or earlier). Though the cover crop did not aid in weed suppression in Ose’s study, he is committed to using cover crops because he has personally witnessed their ability to hold soil in place and prevent erosion on his farm. As such, Ose intends to expand the number of seed corn acres he interseeds with a cereal rye cover crop in the spirit of continued learning. “We saw the possibility that weed control with cover crops can exist because the earlier interseeding date (July 1) produced more growth and the potential for competition with the weeds than the later interseeding (Aug. 6),” Ose said. “We just haven’t figured out how to make weed control with cover crops consistently work on our acres just yet.”

Appendix – Trial Design and Weather Conditions

Figure A1. Sam Ose’s experimental design. He implemented four replications of each of the three treatments (12 strips total). This design allows for statistical analysis of the results

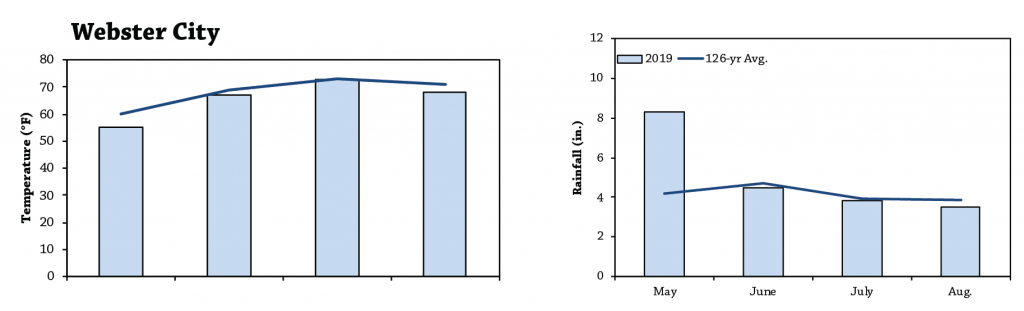

Figure A2. Mean monthly temperature and rainfall for May 1, 2019 through Aug. 31, 2019 and the long-term averages at Webster City, the nearest weather station to Ose’s farm (about 15 miles away).[3]

Funding Acknowledgement

This material is based upon work supported by the Natural Resources Conservation Service, U.S. Department of Agriculture, under number 68-6114-17-010. Any opinions, findings, conclusions, or recommendations expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

References

- Gailans, S. and J. Boyer. 2015. Effect of Seeding Date on Cover Crop Performance. Practical Farmers of Iowa Cooperators’ Program. https://practicalfarmers.org/research/effect-of-seeding-date-on-cover-crop-performance/ (accessed October 2019).

- Gailans, S. and J. Boyer. 2016. Interseeding Cover Crops in Seed Corn at the V4-V6 Stage. Practical Farmers of Iowa Cooperators’ Program. https://practicalfarmers.org/research/interseeding-cover-crops-in-seed-corn-at-the-v4-v6-stage/ (accessed October 2019).

- Iowa Environmental Mesonet. 2019. Climodat Reports. Iowa State University. http://mesonet.agron.iastate.edu/climodat/ (accessed October 2019).