What is the Opposite of a Monoculture?

This is a guest post by ISU students Caroline Oliveira, Gabrielle Roesch and Maria Van Der Maaten, summarizing research they conducted in fall 2012 for a class through the Graduate Program in Sustainable Agriculture at Iowa State University.

Biodiversity is absolutely essential for a healthy ecosystem and some would argue it is vital for long-term productivity of the land. We need to better understand what farmers think about biodiversity and how that translates to their actions in the field. Biodiversity has many interpretations but generally is seen as diverse genetics, species and species interactions within ecosystems. Biodiversity is found in both cultivated and wild systems and is reliant on landscape-level ecosystem interactions. To enhance management practices that increase biodiversity, we must better understand the farmers’ perspectives. Therefore we wanted to answer the question: How do Iowa farmer members of Practical Farmers of Iowa (PFI) and Women, Food and Agriculture Network (WFAN) perceive biodiversity on their farms? We explored this question through an online survey and conducted three in-depth interviews.

Most participants thought biodiversity included all species on the farm, including crops, livestock and wild species. One- quarter of participants see biodiversity primarily as diversity of crops and domestic animal breeds. The interview responses mirror the survey results. Seth Watkins, a farmer in southeast Iowa, defined biodiversity as “the opposite of a monoculture… finding the proper mix of plants and animals that complement, protect and improve the environment around them.”

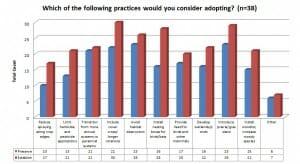

The majority of respondents were already implementing various management practices that enhance biodiversity on their farms (see Table 1. Click to enlarge). Overall, respondents wanted to adopt more practices rather than simply increase what they already had. The practices with the biggest difference between what farmers currently implement and what they want to establish included limiting herbicide and pesticide applications, increasing cover crops and installing nesting boxes for birds and bats. On the whole, it appears that participants are very interested in managing their farming operations to encourage greater biodiversity.

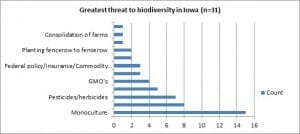

Survey respondents were critical of issues in Iowa that they believed negatively impacted biodiversity (see Table 2. Click to enlarge). Monoculture, and specifically the emphasis on corn production, was identified as problematic, particularly the price of corn and beans driving people to plant more crops fencerow to fencerow. Interviewees echoed this idea about monoculture and Roundup Ready (GMO) crops being the antithesis of biodiversity. One PFI farmer from central Iowa said: “A lot more people should worry about what they are doing. The soybean and corn guys are going to kill the whole population. They are going to go until there is no soil left, so I think we need to change our practices. I can’t save the world, I’ve only got 500 acres.” A similar notion was expressed by PFI and WFAN farmer Chris Henning who said, “I think it is going to take something like Hurricane Sandy to convince people that nature means business and that we need to do what we can do.”

Farmers provided valuable information that can help pave the way for future research on biodiversity in Iowa. Our results show that participants perceive biodiversity as diversity of plant and animal species, but they are also aware of microorganisms, especially in the soil, that are essential for a healthy ecosystem. Participants indicated that the diversity on their farm has benefitted them, both financially and ethically. In addition, PFI and WFAN farmers appear to be very willing to improve their management strategies to increase biodiversity on their farms and to further develop habitat for wild species.

Outreach and education needs to emphasize specific species of concern in Iowa while promoting management strategies that could improve habitat for these species. Management practices or additions such as adding cover crops, increasing perennial systems, limiting herbicides and pesticides, and providing habitat additions (bird houses or woody debris) are likely to be received well by PFI and WFAN farmers while potentially having positive economic and environmental impacts.