Small Grain Fertility Requirements and Application Strategies

When Albion, IA farmer Wade Dooley thinks back to his first experience growing cereal rye for seed, he recalls, “We went with what we read in magazines, as far as recommended fertilizer rates which was basically – don’t fertilize it, you can grow it and it will be fine. Well, yeah, you can grow it and it will be okay but you’re not going to get good yield and there’s going to be variation in the field.”

While small grain crops like wheat, oats, barley and rye certainly aren’t as nutrient hungry as corn, lack of fertility can lead to lower yields, potentially lower grain or seed quality and field variability that can lead to weed and harvest headaches. A healthy, vigorous crop also has the benefit of being better able to withstand disease – a bonus that may save a fungicide application down the line. On our February shared learning call, we welcomed Dr. Dave Franzen, Extension Soil Specialist from North Dakota State University, to share some ABC’s of small grains fertility.

Nitrogen Rates & Timing: A Balancing Act

“Nitrogen rates for winter wheat are not like corn where if you overdo it, it’s okay. It may be an economic loss or an environmental problem, but it doesn’t affect yield too much,” Dave says. “If you put too much N on winter wheat it will fall down.” A fallen or lodged wheat stand is more difficult to harvest, and if the crop lodges before flowering (usually May-June) then you could also lose yield in addition to having a harvest headache. This same issue plagues all the small grain crops, but can be even worse in taller small grains like oats, rye and triticale.

Fertiliizer must be applied carefully, especially in taller small grains like rye which is prone to lodging in soils rich in nitrogen.

Because of this balancing act, it’s important to approach your fertilizer program with an eye for detail. First, think about the crop rotation. Is there a nitrogen credit from a soybean or other legume crop? These credits are particularly applicable when planting a winter small grain in the fall right after soybeans and do not account for the soybean N credit. “If you go ahead and put on your normal wheat N rate recommended in your state, the wheat could go flat,” Dave says. Take manure into this consideration as well. It’s always best to get manure tested so you’re working with good data to determine how much additional fertilizer you need.

“Instead of one pound of removal which is what’s common with corn, oats or wheat we’re talking more like three-quarters or eight-tenths of a pound,” says David Weisberger, a former ISU graduate student who studied oat agronomy in Iowa. Between the small grains, wheat has been bred for yield response to N so higher N applications are possible for wheat. Whereas crops like oats, rye and triticale can’t handle high N rates without lodging.

The precise N rate that you should be shooting for also depends on your local conditions, particularly the organic matter level in your soils. State recommendations can get you close, but even they should be taken with a grain of salt. “In North Dakota you should use maximum return to N rates rather than a yield goal to calculate nitrogen rate,” Dave says.

Timing nitrogen application can also be a balancing act. Some people prefer to put some nitrogen on in the fall with or before a winter small grain, but this practice can be risky. “We don’t want the wheat to get too vegetative before the winter to avoid winter kill,” Dave says. “When the wheat hasn’t grown a whole lot and hasn’t got too big it can withstand snow and cold conditions, but it can get too vegetative with a nitrogen application and isn’t as hardy.”

The exception is manure and other organic fertilizer sources, which release N more slowly than chemical fertilizer N. If you have a higher C:N ratio in your fertility source, like composted manure, putting it out in the fall can allow the necessary time for that N to start mineralizing and become plant available. “If your state and your land allow it, a fall application would be good to allow that manure to start breaking down,” Dave says.

The spring is physiologically the best time to apply fertilizer to encourage higher yields. “During tillering and jointing when you apply nitrogen at this point you greatly enhance the plant’s ability to put on tillers which does potentially increase your yield ceiling by increasing the number of seed heads you can have in a given surface area,” David Weisberger says.

As for the rate that should be applied in the spring, Dave Franzen suggests consideration of the early top-dress N recommendations in a University of Kentucky resource for fertilizing winter wheat. It walks through how to assess your plant stand (plants per square yard or foot) and then time nitrogen based on whether you’re on target for your stand and tillering. “Another thing a person could consider is when you go out and put your spring application on, usually pretty early in the season, you can put an extra 30-50 pounds in a strip,” Dave says. “If that looks healthier, more vigorous then the rest could use a higher dose, if there’s no visual difference then your rate was probably good.”

For spring applications into a growing small grain crop you can stream on liquid 28% or apply urea treated with NBPT urease inhibitor. “The original NBPT product Agrotain™ is well-researched and the efficacy of its active ingredient and rate per ton of urea is almost totally effective in ammonia volatilization inhibition. The product had 26.7% NBPT and was applied to urea as it is being mixed at a rate of 3 quarts per ton.

Today, many products contain NBPT, but it is important that they be applied to deliver the same active ingredient per ton of urea as the original formulation,” Dave says.

Broadcasting 28% is unwise due to the burn potential of the fertilizer on the small grain foliage. Streaming 28% greatly reduces the burn if the wind does not break up the fertilizer stream.

Pay close attention to fertilizer application practices, custom applicators particularly may not be used to carefully avoiding doubling up on their passes – especially on the ends where shut-offs aren’t as quick as they should be. Wayne Koehler grows rye and oats near Charles City, IA, “I remind the applicators that put [my fertilizer] on every year to be very careful to avoid overlap or double any place when they’re turning around.”

Phosphorous: Apply Early!

Phosphorous is the other really important nutrient for small grains as it results in stronger, more extensive root systems and strong, sturdy shoots that promote winter hardiness and can help prevent lodging. Dave is a firm believer in applying starter phosphate at the time of small grain planting, particularly for winter small grains. His colleague, Dr. R.J. Goos worked on phosphate (P) for about 20 years. His recommendations are that wheat will respond to a row-starter even at high soil test P values, particularly in the northern plains. Application to winter wheat at planting also helps the plant have better vigor so the crop can come out of winter in good condition.

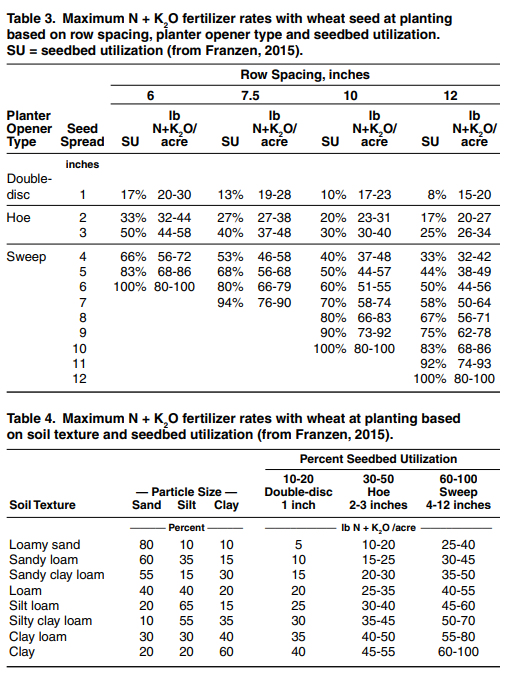

The amount of fertilizer you can put on at planting will be limited by your planter set up, Dave has published the following charts that help navigate the fertilizer levels you can apply with your planter and with your soil.

Example from: Fertilizing Winter Wheat

Potassium, Sulfur and the Rest of the Alphabet

“Wheat is not as responsive to potassium as corn is, it’s closer to soybeans,” Dave says. Soil potassium (K) can be measured reliably with soil tests and if further applications are necessary the test will show how much is needed. Most K fertilizer also contains chloride (Cl). In regions where potash is regularly applied, soil test Cl values will probably be high enough to achieve maximum yields.

In the northern plains where potash fertilizer is not regularly applied, soil test values can be quite low. Even then, the wheat yield increase due to Cl is generally low, so it mostly makes sense to only apply Cl when small grain prices are high and potash prices are low. There are some areas in Indiana and Michigan that have historical manganese problems, but for other areas this is an unusual and rare element for concern. Copper (Cu) may be a concern in peat and muck soils, with organic matter content greater than 10%, but if the organic matter is less, it is a very rare concern. In North Dakota, importance is confined to extremely eroded, very low organic matter deep sandy soils, and its value is extremely site-specific.

Sulphur (S), on the other hand, has risen in our understanding of its importance to small grain performance. “S deficiency in North Dakota is so pervasive now that you have to mention it,” Dave says. “Canola, corn and small grains are particularly susceptible to S deficiencies.” Unfortunately, there aren’t soil tests that can tell you S levels reliably. PFI member Tim Sieren, who farms near Keota, IA, has taken tissue samples of his rye early in the season and detected Sulphur and Boron deficiencies that way. “We added Boron and Sulphur to [our fertilizer plan],” Tim says. “We did a side by side yield check and it did a 10 bushel per acre better on some of it, some of it was up 15-20 bushel per acre difference depending on soil type. That’s the best response I’ve gotten out of any fertilizer on rye.” Dave adds that Sulphur is a spring fertilizer and should never be put on in the fall.

Depending on the moisture and slope, you may need to apply up to 10 pounds per acre of Sulphur as a sulfate or thiosulfate form. Elemental S is not particularly useful. “Generally, sandier soils and hill tops and slopes, particularly when they’ve been wet in the fall and/or spring, will respond most to S fertilizer,” Dave says.

For more information on small grain fertility check out these other resources:

- Fertilizing Winter Wheat SF1448 Franzen – NDSU

- Fertilizing Malting and Feed Barley SF723 Franzen & Goos – NDSU

- Fertilizer Application with Small Grain Seed at Planting SF1751 Franzen – NDSU

- Fertilizing Winter Rye SF1462 Franzen – NDSU

- Fertilizer Management for Winter Wheat Murdock, Grove and Schwab – UKY

- Rotationally Raised Episode 6: Growth Stages, Fertilizers and Fungicides Podcast – PFI

- Rotationally Raised Episode 6: Growth Stages, Fertilizers and Fungicides Video – PFI

- Fertilizers, Herbicides and Fungicides for Small Grains Blog – PFI

To receive notice of upcoming call topics and other small grain resources straight to your inbox sign up for our monthly small grains e-newsletter.