Inspired to Create Community

Rick Exner played a key role in PFI’s founding story, and its first 20 years

Many PFI members – especially long-time ones – are familiar with the outlines of Practical Farmers’ founding story: how in 1985, in the midst of the farm crisis, Dick and Sharon Thompson and Larry Kallem organized a group of farmers eager to work together testing novel solutions to the pressing economic, social and ecological farming challenges of the time.

But the story of PFI’s genesis wouldn’t be complete without acknowledging the pivotal role played by another leading light of PFI’s early years: Rick Exner.

Long before the momentous day when Practical Farmers formally coalesced, Rick was working closely with the Thompsons: keeping beehives on their farm, conducting research, helping at field days – and talking with them about the need for an organization like Practical Farmers of Iowa.

As the fledgling organization took root, Rick took on several vital supporting roles, from helping Dick solidify PFI’s now renowned on-farm research methodology, to joining in on early member recruitment tours around Iowa, to co-founding and managing the PFI quarterly newsletter – all initially as part of a core cadre of volunteers working behind the scenes to bolster the nascent organization.

“We were doing some things from the very beginning to try to act like an organization,” Rick says. “In 1985 and ’86, we still had no staff. So if it involved grunt work, fellow [Iowa State University] graduate student Ricky Voland and I were the volunteers who did it – though there were some other students who helped too.”

“We were doing some things from the very beginning to try to act like an organization.” – Rick Exner

Early Years

Rick was born in New York State, but was just 1 year old when his family moved to Ames so his father, Max, could take up a position as ISU’s state extension music specialist. Before relocating, his mother, Eileen, had worked in Upstate New York as an extension home economist for Cornell University. He and his three sisters grew up in Ames, surrounded by music and their parents’ deep appreciation for the value of the land-grant mission.

After receiving his bachelor’s degree in sociology from Grinnell College, Rick ventured east to Cambridge, Massachusetts, where he worked at mental institutions and for afterschool programs. While there, he encountered food cooperatives for the first time – and their close-knit, people-centered infrastructure opened his eyes to the powerful link between local food and community.

“At that time, they were all set up as preorders,” Rick says. “They were divided geographically, and every Sunday night there would be a potluck, and we’d put our orders in for the food. On Tuesday, a delegation of us would go to the terminal produce market outside Boston to pick up the food, take it back and break it down into individual orders. We had a buyer on the market through the New England Food Co-op Organization, NEFCO.

“It was a kind of a community function – and through that, I made some of the best friends in my life. Because we were geographically defined then, they were my next-door neighbors too. So through that, I really saw food as a way to community.”

Rick became intimately involved with NEFCO and decided to stay in the area, taking on a variety of odd jobs so he could volunteer with the co-op as much as possible. “I was sort of a full-time volunteer,” he quips. While there, he and some friends started a small cider venture gathering apple “drops” – surplus fruit – from heirloom varieties on old estates across New Hampsire.

“They were wonderful old varieties that you can hardly find now, which make the most wonderful cider,” Rick says. “We had friends in New Hampshire who owned a hydraulic cider press, and we found we could make some money – and be very competitive price-wise – by collecting those apples for free, pressing them into cider and selling it to the co-ops around Boston.”

While he loved working with the co-op, Rick started to think more long-term about his prospects. Invigorated by his newfound commitment to food and community, he realized staking out a career in agriculture could knit those passions together.

“It began to dawn on me that if I was going to do something other than drive the truck for the co-op for the rest of my life, I needed to get some knowledge and actually study agriculture,” Rick says. “That’s when it started making all kinds of sense to come back to Ames, where my parents still were, and take up my education here.”

The Path to PFI

Rick returned in 1978 and started taking classes at Iowa State University that fall, initially enrolling in undergraduate courses to catch up on science prerequisites needed to enter an agronomy graduate program. Soon after returning to the area, however, Rick started seeking out area farms “that were doing something different” where he could help out and learn more about agriculture. That’s how he discovered Dick and Sharon Thompson. While they didn’t need any farm help at that time, Rick soon crossed paths with them again when the ISU Agronomy Club – which was open to all students – invited the Thompsons to give a presentation at one of its meetings.

Rick had started keeping bees and decided to approach the Thompsons about keeping some of his hives on their Boone-area farm. “After the talk, everybody wanted to talk to Dick,” Rick recalls, “but I went over to Sharon and said, ‘Say, we’ve got some beehives. Do you think we could put some on your land?’ ”

Sharon and Dick agreed, and as Rick had hoped, the arrangement gave him the chance to interact weekly with the Thompsons. By the time he started his graduate program in 1983, studying under ISU agronomy professor Richard Cruse, he knew the Thompsons well enough to ask about using their farm for his graduate research, which focused on intercropping legumes between rows of corn.

Over the next two years, Rick attended field days the Thompsons hosted and brainstormed ideas with them, leading to serious conversations with Dick about the need for an organization like Practical Farmers of Iowa that could help farmers use research to make better decisions. By the time the now-famous biological farming conference took place in 1984 – where Dick asked how many farmers wished to form a group based on sharing information with one another – Rick had been a key behind-the-scenes thinker helping crystallize the vision for an organization like PFI.

“Dick and Larry had been doing a certain amount of strategizing, and Dick and I were doing a fair amount of strategizing,” Rick says. “At that biological farming conference, I got up early in the meeting and offered the opinion that, while the program being offered was great, farmers also needed an organization where they could share information farmer-to-farmer.

“Later in the day, Dick got up and said he knew ‘a young man’ who was willing to help start an organization. Some people assumed it must be me, but Dick was referring to Larry Kallem. The positive response just confirmed our thinking that there was a need for something like this.”

Paving the Way for Farmer-Led Research

One of Rick’s lasting contributions was his role in helping to cement the now renowned ethos and research methodology of the Cooperators’ Program, established in 1987. Dick had been working on ways to conduct on-farm research for years – and to empower farmers to lead their own trials. After Rick entered the scene, they brainstormed research design together, but were still learning and adapting – and sometimes they made mistakes.

“I remember one year, Dick had laid out maybe four different treatments for a trial, and just logically divided the whole field up into quarters, doing one practice on each quarter,” Rick recalls. “We got the most gosh-awful results – and it finally sank in that we weren’t measuring the treatments we put out. We were actually measuring the difference between this corner of the field and that corner. That was a learning experience for both of us.”

Soon after, Rick attended a farming systems conference at Kansas State University where he heard a talk by Chuck Francis, professor of agronomy and horticulture at the University of Nebraska–Lincoln. Rick approached him afterwards for advice on the research design dilemma.

“I said, ‘We’ve got this problem. We’ve been trying to do on-farm research and it’s just coming out screwy. How can we come up with a design that’s practical? That you can basically do from the seat of a tractor, but will also give you a good, reliable statistical outcome?’ Chuck just said, oh, a paired comparison. And the scales fell from my eyes, as they say. I came back and told Dick, and he said yeah, with narrow strips.”

The revelation led to the powerfully simple – yet statistically robust – version of the randomized complete block design so central to the Cooperators’ Program. The approach, Rick says, put farmers in charge by stripping daunting complexity, yielding reliable answers and simplifying the math needed to analyze results.

“The beautiful thing about that design is farmers can do the math themselves,” Rick says. “We thought it was important that farmers be in charge of the process from beginning to end. By the time Dick decided we needed a Cooperators’ Program, we had a good research design people could use.”

From Volunteer to PFI Staff

With funds scarce in PFI’s early days, the group’s core tasks were carried out by a handful of dedicated volunteers. Rick and friend Ricky Voland, a graduate plant pathology student, decided PFI needed a newsletter. They named it “the Practical Farmer” and started publishing it quarterly, mailing the debut issue in spring 1986.

Though full-time students, the two managed the entire publication, from writing content and manually cutting and pasting the layouts – which they’d then take to the copy center to print – to collating, addressing, stamping and mailing the finished newsletters. The process was laborious, and run on a shoestring budget.

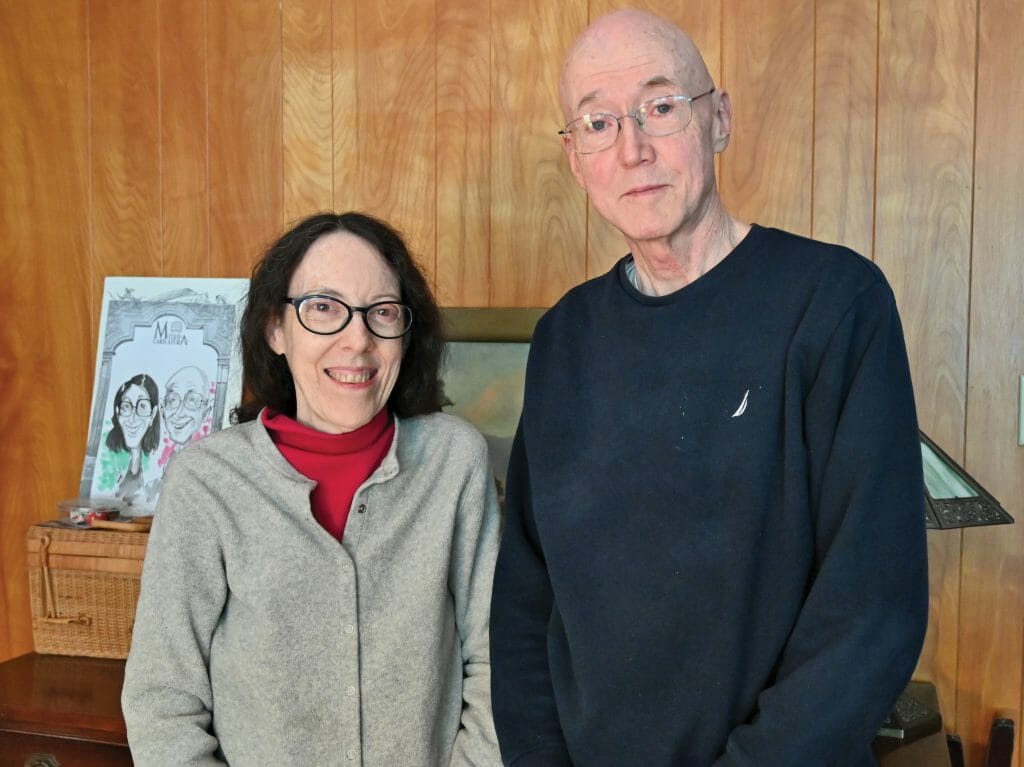

Rick recalls how his wife, Sue Jarnagin – whom Rick met in the late 1970s in Fargo, North Dakota, thanks to a mutual friend working at the Fargo food co-op, and who then came with him to ISU – had to ask their international women’s group to give them $40 so they could put out an issue of the newsletter. “It was hand-to-mouth,” he says, “but there was nowhere to go but up.”

In the late 1980s, funding started trickling in – first from Dick’s friendship with Jean Wallace Douglas, of the Wallace Pioneer Hi-Bred family. Then, Jerry DeWitt, at the time working as the ISU Extension sustainable agriculture specialist, included PFI in a water quality funding proposal. By that time, Rick had been working towards his doctoral degree in agronomy at ISU.

He and Dick drafted the proposal text, with coaching from Jerry, and the resulting funds enabled PFI to hire its first full-time staff member. When the initial hire left after just a couple of months, Rick stepped into the role as PFI’s farming systems coordinator in 1989 – a position he held for the next 20 years.

That funding also helped establish a close collaboration between PFI and ISU that continues today. While a central aim of Practical Farmers was to connect farmers to each other, Rick says the early PFI participants also saw a second important role. “We saw ourselves providing a constituency for scientists who were working on some things that might not have gotten support otherwise.”

After PFI

After leaving PFI in 2009, Rick embarked on a variety of projects, from working with the U.S. Census Bureau to obtaining grant funds through the group Iowa-Yucatan Partners to develop a water stewardship teaching module for trade schools in Yucatan, Mexico, and traveling there to help conduct the training. Since 2013, Rick has been involved with AMOS (A Mid-Iowa Organizing Strategy), helping build local partnerships and support systems on behalf of immigrants.

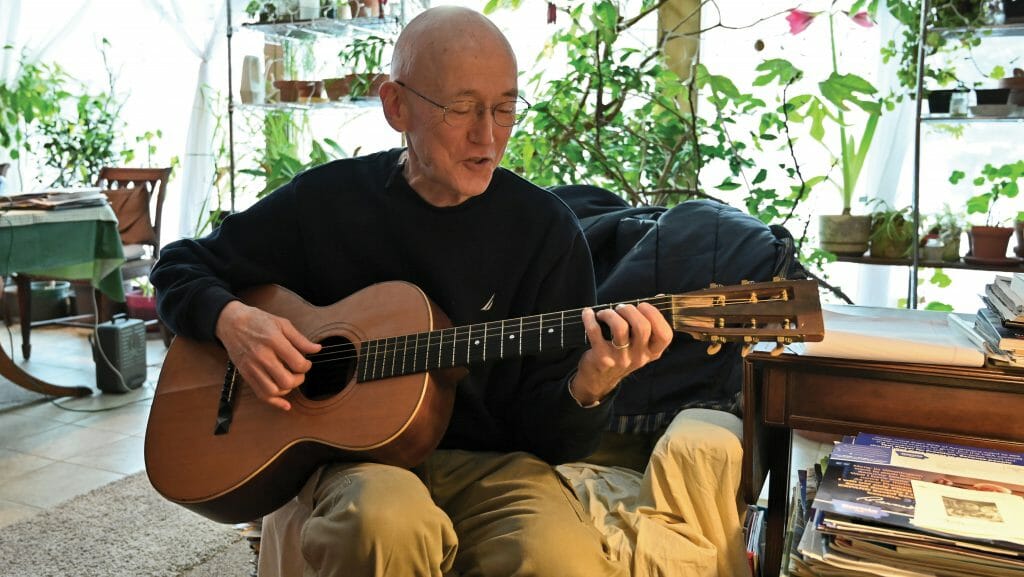

Throughout all these endeavors, music has been central to Rick, a guitar player who occasionally performs at Berry Patch Farm, near Nevada, or the Ames Main Street Farmers’ Market, singing a motley mix of blues, country, Latin and original compositions.

For about 10 years, Rick was also part of the central Iowa band The Porch Stompers, a long-running collaboration with PFI members Alice McGary and Nate Kemperman and local banjo legend Merle Hall. When not busy with AMOS or his music, he and Sue keep busy working on renovations to their house and an intensive garden: their city lot holds 19 fruit trees.

When asked about PFI’s legacy and his role in PFI’s formative years, it all boils down to community for Rick. “Dick and Sharon really embodied a welcoming community, and I think it set the tone in a lot of ways,” he says. “People would drive an hour to get to a field day and say, ‘I can talk to you guys but I can’t talk to my neighbors when it comes to this kind of farming practice. Here, I can ask my questions and get some intelligent responses.’ I think that’s the point where PFI really started becoming a community – and it makes me feel I was doing something right.”

“People would drive an hour to get to a field day and say, ‘I can talk to you guys but I can’t talk to my neighbors when it comes to this kind of farming practice. Here, I can ask my questions and get some intelligent responses.’ I think that’s the point where PFI really started becoming a community – and it makes me feel I was doing something right. – Rick Exner