Reflecting on History to Create Resilient Paths Forward

Members are increasingly acknowledging original Indigenous occupants

Often when people talk about the land they farm, they refer to the generations of their family that farmed before them. But you may have noticed that, in recent years, more people are starting to reflect farther back to recognize the Indigenous peoples who stewarded the land first. Here are some examples of land acknowledgements that have occurred at PFI events or by PFI members this past year.

Peg Bouska

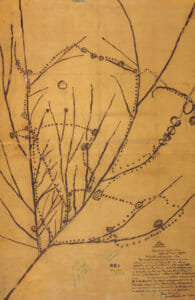

According to the Office of the State Archaeologist, based at University of Iowa: “The 1837 Ioway Map (known sometimes as No Heart’s map) was created by one or more unnamed Ioway Indians, for a meeting that took place on October 7, 1837 in Washington D.C. “Illustrated on the map are villages and travel routes of the Ioway, plotted on lakes and rivers within an area of nearly a quarter of a million square miles of the Upper Midwest and eastern Great Plains. But the map also illustrates the movements of the Ioway throughout time, from their traditional place of origin at the estuary of Green Bay in present-day Wisconsin about 1600 AD through their journeys between the Wisconsin woodlands and the plains of eastern Nebraska for the next 237 years.” (Map source: National Archives and Records Administration)

In October 2020, sisters Peg Bouska, Carol Bouska, Sally McCoy and Ann Novak were awarded PFI’s Farmland Owner Legacy Award for the work they’ve done creating and progressing towards shared goals for their farmland near Protivin, Iowa, including efforts to improve conservation, community vitality and healthy food. In her acceptance speech, Peg said: “We want to recognize our great privilege to own this land, and that the first people to live on it were displaced. This includes the Sac and Fox Tribe, the Meskwaki Nation, who still live in Iowa. This legacy process has led us to grapple with that fact.”

According to Northwestern University’s Native American and Indigenous Initiatives, a land acknowledgement recognizes and respects Indigenous people as traditional stewards of the land and the enduring relationships that exist between Indigenous people and their native lands. Peg, who lives in Iowa City, Iowa, first heard a land acknowledgement at a PFI beginner farmer field day several years ago. “It was really cool to hear a couple just starting out acknowledge the history of their land,” she says. Hearing others acknowledge that history planted a seed for Peg.

A renewed focus on the farmland that had been passed on to them inspired Peg to do a land acknowledgement on behalf of her and her sisters. “In the last year or so,” she says, “my sisters and I have been much more focused on connecting to our land.” She, Carol, Ann and Sally are transitioning the farmland they are stewarding to more regenerative, soil-building practices. To do this, they need to better understand the shape every acre is in. Working with consultant Ecological Design and with Climate Land Leaders – a group that works with farmland owners to help them transform their land with conservation practices – Peg and Carol, who lives in Minneapolis, conducted a land walk.

“The Native peoples who used to live here were pushed off the land directly or lost access to it because of the Homestead Act. Our family has benefitted for more than 100 years financially, plus we were able to grow up with the benefits of life on the farm . . . . Acknowledging what happened is the starting point for healing.” – Peg Bouska

“We walked all of our acres and were able to see and feel the nature of ecology and the geological history,” Peg says. “Along with this, you feel the human history. I have always been interested in Native history, and am feeling this connection really intently right now. The Native peoples who used to live here were pushed off the land directly or lost access to it because of the Homestead Act. Our family has benefited for more than 100 years financially, plus we were able to grow up with the benefits of life on the farm. That is at the expense of people who previously had that life here, which was taken from them. Acknowledging what happened is the starting point for healing.”

Wendy Johnson

Wendy Johnson, who farms near Charles City, Iowa, has been giving this land acknowledgement in presentations recently: “The land we steward is located in what is now Floyd County, Iowa, land of the Ioway peoples for centuries. When the Ioway were pushed south and westward, it became neutral territory of the Oceti Sakowin, the Wahpeton Dakota and the Sauk and Meskwaki, and later yet the Ho-Chunk peoples.” For the past few years, Wendy has been doing research on Iowa’s Indigenous tribes and historical landscape – and she emphasizes a land acknowledgement is not “a pat-yourself-on-the-back kind of thing, but the beginning of a long, hard journey to mend relations and honor the people here before us that were removed from the land that we now call our home and farm.”

“For me,” she adds, “it is a spiritual journey. I’m learning what Iowa used to look like, and could look like again. As a farmer and land steward, Mother Nature is my teacher. I’m promoting grasslands, grazing and attempting to mimic what bison did. When I’m walking this land and I see wildlife diversity return, soils alive and a synchronicity happening, it gives me hope that I am moving in the right direction, a constant reminder of the people, communities and ecosystems that were here before me.”

This past year, due to the pandemic, Wendy has been able to attend conferences on her bucket list that she has not been able to attend in the past, including those organized by Bioneers, the Biodynamic Association and EcoAg, as well as the collaborative “Regenerate” conference held annually by Quivira Coalition. “Most sessions began with land acknowledgements from attendees wherever they were from across the nation and world, as well as storytelling and viewpoints shared from Indigenous people,” Wendy says. “It was powerful and inspiring to listen to, and gave me the courage to say out loud what I was feeling.”

Meghan Filbert and Omar de Kok-Mercado

PFI’s livestock program manager, Meghan Filbert, and her husband, Omar de Kok-Mercado, are also beginning graziers. In December 2020, they hosted a central Iowa grazing group get-together near Pilot Mound, Iowa. As guests gathered, Meghan and Omar explained what they know of the history of the land they graze, pointing out that the farmhouse was built in 1862 as a stagecoach inn during the Civil War and sharing what they have learned about the Ioway and Sioux tribes that once occupied the land up and down the Des Moines River. They also noted the two nearby Native American burial mounds that sit on a ridge above the Des Moines River and are currently covered in native prairie grasses, most notably big bluestem and milkweed.

“We look at Iowa’s natural heritage of prairies and savannas as relics of an Indigenous farming legacy,” Omar says. He and Meghan aim to honor the land and its past peoples by working to reconstruct the oak savanna as a silvopasture, using goats and sheep as their primary vegetation management tool to control an understory of invasive plants. Meghan adds, “We’re keeping our understanding of Indigenous land stewardship close to mind as we plan next season’s grazing and fire management.”

John Gilbert

In John Gilbert’s storytelling at our annual conference, he speaks of people who have inhabited the land he farms near Iowa Falls, Iowa, before him, from his ancestors to Indigenous predecessors. He talks about how their spirits “are around the structures they left behind, the trees they planted, even the shape of the landscape.”

“Our challenge,” he says, “is to recognize their presence, their contributions.” Read John’s full story on pages 20-21 of this magazine.

“We look at Iowa’s natural heritage of prairies and savannas as relics of an Indigenous farming legacy.”

– Omar De Kok-Mercado

Steve Gabriel

Many PFI members attended a webinar on silvopasture presented by Steve Gabriel, co-founder of the nonprofit Wellspring Forest Farm in Trumansburg, New York, that PFI sponsored in fall 2020. Here are excerpts from Steve’s land acknowledgement:

“I think it’s really important to presence the Indigenous lands that we’re on. The Gayogo̱hó꞉nǫʼ is the name for the Cayuga people . . . . We’re building relationships and learning about a really challenging slice of what it means to own land in New York State . . . . We honor these lands and recognize that we’re on Indigenous land. These people are presently here and have a future here as well.” Steve acknowledges that the farm wrestles with the concept of land ownership.

What’s Next

Wendy, Peg and Meghan all said that land acknowledgements were just a first step for them. They are thinking about what comes next as far as land stewardship and how they can play a part in remedying damage done to Indigenous peoples. They don’t know what that looks like, but realize awareness is the first step, and they have started this journey.

Should others do land acknowledgements? “There is no right or wrong answer,” Wendy says. “It is a personal choice. We as farmers need to begin somewhere in our journeys toward being good stewards of the land, and a land acknowledgement can be that starting point. We need to think in wholes to move forward. I do not view land acknowledgments as a divisive or a political act.”

Learn More

- To learn more about the Indigenous people who came before you, the website Native Land (native-land.ca) is a good starting point. You can enter your location and find who inhabited the land you live or farm on before colonization.

- The Iowa Historic Indian Location Database, a project of the Office of the State Archaeologist, is using overlooked historical sources to map Native American sites in Iowa from the era of the earliest European explorers to the modern period: iowahild.com

- To learn more about Iowa’s Indigenous history, read “The Indians of Iowa” by Lance Foster, a member of the Ioway Tribe of Kansas and Nebraska.