Asking Those Who Knew

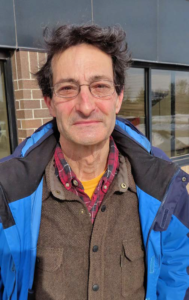

Matt Liebman has always had a close connection to PFI – he was aware of the organization before he even moved to Iowa. Even so, it’s striking to see just how much his research interests have overlapped those of PFI farmers over the course of his career.

When the two of us spoke in early February 2022, Matt had recently retired from the Department of Agronomy at Iowa State University, where he had been a faculty member since 1998 and served as the Henry A. Wallace Endowed Chair for Sustainable Agriculture since 2007. Throughout his tenure at ISU, Matt’s research, teaching and outreach work focused on ways to use ecological processes to create farming systems that are productive, profitable, resilient and environmentally sound – concerns that overlap considerably with the interests of PFI members.

It was clear during our conversation that Matt, who is also a lifetime PFI member from Ames, Iowa, had been reflecting on this overlap: “Looking at early issues of the Practical Farmer, going back to 1988, it’s shocking how similar both the questions and the answers were then to what they are now,” he says. “Questions about optimal crop rotations, stewarding natural resources, habitat for wildlife – that stuff was being asked by PFI farmers and others back in the 1980s.”

Trusting Farmers as Experts

Since arriving at ISU in 1998, Matt’s research topics included integrated crop-livestock systems, weed ecology, soil quality, prairie and wildlife habitat. You’ll find many of these subjects at the forefront of PFI field days, meetings, conferences and farminars, and in the pages of this magazine today. Through the years, Matt has been generous with his time and knowledge, frequently speaking to or writing for PFI audiences. Wasting no time since retiring, he also recently joined PFI’s board of directors.

“Matt always held farmers in the highest regard,” says Gina Nichols, former graduate student of Matt’s who now works as an assistant research professor at the Swette Center for Sustainable Food Systems at Arizona State University. “He loved going to the field, and his work was always motivated by a desire for things to be better.”

Matt says this motivation stems from experiences he had early in his career working with farmers from California to Maine. While he enjoyed the science of tuning cropping systems to yield better with lower environmental impact, he also came to enjoy the people as much as the subject matter.

Matt Liebman speaks to a group of farmers visiting the ISU Marsden Farm near Boone, Iowa, during a field tour in 2003.

“Farmers are very good observers and they have a lot of practical knowledge about what works and what doesn’t,” he says. “One of my brothers always said: ‘If you want to find out the answer to a question, ask somebody who knows.’ ” That’s exactly what Matt did throughout his research and teaching career.

Before Matt came to ISU, he worked at the University of Maine, just outside Bangor, on the southern end of a region called the Maine Highlands. While there, he regularly took his students to visit with local farmers; consequently, his work included crops like potatoes, barley and dry beans. When he moved to Iowa and had to decide what to focus his work on, he knew where to begin – and whom to look to for guidance.

“Farmers are very good observers and they have a lot of practical knowledge about what works and what doesn’t.” – Matt Liebman

“The first year I moved to Iowa, I didn’t do any experiments,” Matt says. “I spent about a day a week at Dick and Sharon Thompson’s farm. I would sit in the tractor with Dick while he was doing farm work and listen to him describe what he did in terms of crop and livestock management.”

Dick and Sharon, of course, are the co-founders of Practical Farmers of Iowa who laid the groundwork for the organization’s on-farm research and farmer-to-farmer knowledge exchange. Matt had been aware of PFI long before he came to Iowa, having read about about the organization in Rodale Institute’s New Farm Magazine in the 1980s. Matt was also familiar with the Thompsons, having met them and other PFI farmers when he traveled to the Midwest for sustainable agriculture meetings.

“My interest was at the level of land management and how you take care of the land that’s being used in such large quantities,“ Matt says. “Most of the land for crop production in Iowa is for corn and soybeans, and I wanted to be relevant to those systems. [The Thompsons and PFI] seemed like a reasonable place to start.”

A Trial is Born

“Dick was really interested in weeds,” Matt says. The Thompsons’ cropping system included corn, soybeans, oats and alfalfa; composted cattle manure and some purchased fertilizer; ridge-till cultivation; and limited use of herbicides for weed control. “Tracking the weed seed bank over the different phases of the Thompsons’ rotation was just eye-opening for me,” Matt says. “And Dick wondered why weeds would sort of magically disappear after the alfalfa crop.”

Matt Liebman pays tribute to the memory of the late Dick Thompson at the PFI Cooperators’ Meeting in December 2013. Matt became familiar with the Thompson farm in the 1980s through Rodale Institute’s New Farm Magazine. When he arrived in Iowa in 1998, conversations with Dick influenced the Marsden Farm cropping systems experiment that began in 2001 and continues to this day.

With their mutual curiosity in mind, Matt designed a set of experimental treatments that mimicked what Dick and Sharon were doing on their farm to see how crop diversity affected weed dynamics. This became known as the Marsden Farm experiment, because the plots were located on an ISU research farm near Boone bearing that name. What started out as “a simple experiment about weeds,” as Matt affectionately describes it, turned into a renowned body of work that continues to impact students, fellow researchers and farmers.

Since the experiment began in 2001, Matt and many colleagues have elucidated numerous benefits of diversified cropping systems compared to the typical corn-soybean system. The diversified systems experience less weed pressure, and thus rely less on herbicides for weed control.

“I believe the most important thing I learned from [Matt] was how to listen to and interact with farmers as experts.” – Adam Davis

Superior physical and microbiological soil properties render purchased fertilizers nearly superfluous. Ultimately, diversified systems pencil out better financially thanks to higher corn and soybean yields and less energy use than the corn-soybean system.

Matt Liebman, Adam Davis and Dave Sundberg show off the elutriator in the ISU greenhouse in the early 2000s. The elutriator was used to wash away soil from cores collected in the field, leaving behind weed seeds. Why all the trouble? “Weeds are a problem for both conventional and organic farmers in virtually every field in every year,” Matt says. “So it seemed like a really great place to focus my attention.”

Matt credits the consistent and repeatable results to the experiment’s longevity. “A lot of the phenomena associated with cropping systems is driven by what happens in the soil, and things that happen in the soil happen slowly, maybe five to 10 years,” Matt says. “So once an experiment is in place for a few years, that allows you to ask questions like, ‘Why? What are the mechanisms that drive crop performance or weed populations?’”

Particularly noteworthy to some was the discovery that insects and rodents were more prevalent in the diversified systems that contained oats and alfalfa, and that they were eating weed seeds.

Former PFI farming systems coordinator, Rick Exner, who worked closely with Dick Thompson and many other PFI farmers on on-farm research for 20 years, was among those who were particularly taken with this finding. “[The Marsden Farm] trials taught us things we hadn’t known,” Rick says. “Understanding the role of winter seed predation by rodents was an important weed management asset of reduced-till systems that we hadn’t connected the dots on until Matt’s systems trial.”

Rick adds, “Matt was also an important link for students studying sustainable agriculture at ISU to become acquainted with the Thompson farm and philosophy.” Because the Thompson farm was just over 5 miles north of the Marsden Farm, Matt and colleagues held field days in conjunction with the Thompsons; together they connected farmers, researchers and students to exchange information and experience. One of those students was Adam Davis, who now heads the Department of Crop Sciences at the University of Illinois. “Matt has many rich talents as a scientist,” Adam says, “but I believe the most important thing I learned from him was how to listen to and interact with farmers as experts.”

Belief in a “Two-Way Street”

That respect for farmers and their experiences is part of what Matt calls a “two-way street between the researcher and farming community.” He says: “Both have something to offer one another. Researchers can provide farmers with useful information, but farmers provide ideas for researchers to investigate.” While it’s clear how much he valued farmer knowledge during his career, it’s equally clear that farmers also value him.

Matt receives PFI’s 2013 Sustainable Agriculture Achievement Award (shovel for a trophy!), presented to him by PFI staffer Sarah Carlson at the January 2013 PFI annual conference.

“Matt is a rare combination of great scientist who is able to explain the science to the average farmer,” says Paul Mugge, an organic farmer from Sutherland in northwest Iowa whose farm Matt would often visit. “Every time I went to the MOSES conference [in La Crosse, Wisconsin], I expected to see Matt there so I could pick his brain. I count Matt as a friend, and I greatly respect him and thank him for his contributions to a better future for all of Iowa and its people.”

A few years after the Marsden Farm experiment began, Matt joined several ISU scientists spanning numerous disciplines to start STRIPS (Science-based Trials of Rowcrops Integrated with Prairie Strips), another long-term agroecological experiment. Among many other things, the research team has found that strategically converting 10% of a crop field to strips of native prairie can significantly reduce soil erosion, improve the quality of water leaving the field and provide an abundance of habitat for birds and beneficial insects.

The results have attracted the attention of scientists, students, conservationists and farmers alike – the practice continues to be evaluated on four ISU research farms and over 30 commercial farms across 14 states (some of them PFI farms), and in 2018, prairie strips were added as a practice eligible for financial support through the federal Conservation Reserve Program.

“Matt is a rare combination of great scientist who is able to explain the science to average farmer… I count Matt as a friend, and I greatly respect him and thank him for his contributions to a better future for all of Iowa and its people.” – Paul Mugge

“Farming is a living tradition,” Matt says. “If you want to keep the types of practices that are necessary for good stewardship in the forefront, you have to at least have a small group of people who are practicing them. [Thanks to PFI], you don’t have to reinvent or find in some archive a description of what a good farming system would look like.”

Matt, a dedicated gardener, poses in his family’s backyard garden beside a crop of chili peppers he was especially pleased with, in Ames, Iowa, in late summer 2009.

He adds: “You can actually go out and talk to real farmers who have made these principles operational, and we understand scientifically what the mechanisms are in terms of biology, chemistry and physics, that allow good outcomes to occur. If and when we get to the point where we can do this on a broader scale, at least we have somewhere to start to scale up from.

“PFI has been one of the best aspects of being in Iowa. It’s a very supportive community. The Iowa landscape and watersheds are still challenged by the same kinds of problems as when the organization began, but there are more farmers in PFI. There are more farmers testing and finding these practices so that, if and when it becomes possible to implement them on a broader scale, that can move forward.”

Why did Matt’s research align with PFI interests? The answer, at least to me, is pretty clear: Because he listened – and because he chose to be relevant.

Before we parted ways after our conversation, Matt shared, “The first thing Dick Thompson asked me when I got to Iowa was, ‘Are you going to stay?’” Lucky for us all – whether we be farmers, colleagues, citizens or, as in my case, former students – he did.