This research was funded by Walton Family Foundation.

In a Nutshell:

- Doug Alert and Margaret Smith typically co-seed oats with a red clover cover underseeding in their organic production system. Concerned about weed control, they were curious to learn if early tine weeding the oats would have any effect on oat yield, intercropped red clover and weed pressure.

- Alert and Smith hypothesized that tine weeding after drilling oats and prior to interseeding red clover could reduce weed pressure, improve oat yield and have no effect on intercropped red clover compared to co-seeding oats and clover with no weed control pass.

- Alert was not able to tine weed the plots due to the amount of residue in the field. The tine weeder, after ‘raking’ up soybean residue, was lifted slightly above the soil surface and had no impact on the soil or seedling weeds. They decided to use a rotary hoe, known to handle a similar volume of residue, instead.

Key Findings:

- Alert and Smith recorded equal oat yields and observed no visual difference in weed pressure between the rotary hoe treatment and their typical practice.

- Rotary hoeing twice and broadcast-seeding the red clover (rather than co-seeding with the oats) cost $32.80/ac more than their typical practice.

Background

The use of rotary hoes, harrows and tine weeders for weed management in small-grains crops (like oats) has been studied across the world.[1–3] This trial was originally designed with a tine weeder because of their increasing popularity among organic farmers who have reported aggressive action and good weed seedling disruption in soybeans. When Alert attempted the first pass with the tine weeder in late April, however, it resulted in too much plugging due to the soybean residue remaining after one preplant tillage pass (see photo). They switched to a rotary hoe which better accommodated the soybean residue.

At left, Alert first attempted to use a tine weeder through emerged oats on Apr. 26, 2020 but it resulted in too much plugging. At right, rotary-hoe pass on Apr. 26 that better accommodated the leftover soybean residue from 2019.

Methods

Design

To test the effect of rotary hoeing on oats, Alert and Smith compared two treatments:

- Rotary hoe – plant oats, then make two passes with a rotary hoe and interseed red clover cover crop on the second pass;

- Control – plant oats and red clover cover crop at the same time followed by no rotary hoe passes (Alert and Smith’s typical practice).

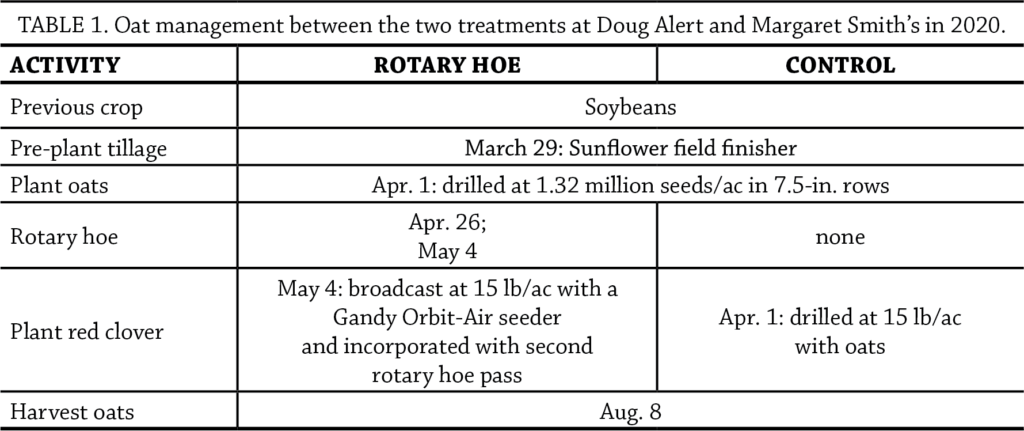

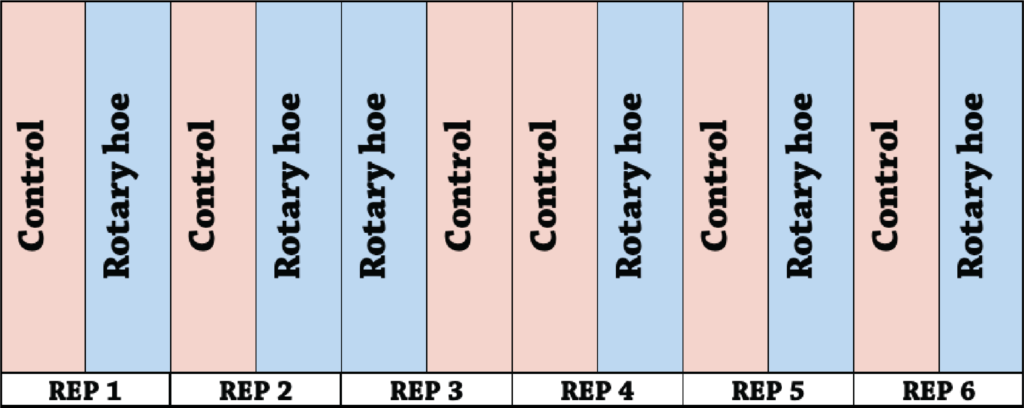

Alert and Smith implemented six replications of the two treatments (Figure A1). Strips measured 30 ft wide by 2,400 ft long. Field management is presented in Table 1.

Measurements

Alert and Smith harvested and recorded oat yields and grain moisture from each strip on Aug. 8. “The oats were quite clean so we were able to direct-cut the oats rather than swath and pick up.” Alert said. Oat grain yields were corrected to 13% moisture.

Data analysis

To evaluate the effect of rotary hoeing on oat yield, we calculated treatment averages and then used a t-tests to compute the least significant difference (LSDs) at the 95% confidence level. The difference between both treatment’s average oat yield is compared with the LSD. A difference greater than or equal to the LSD indicates the presence of a statistically significant treatment effect, meaning one treatment outperformed the other and Alert and Smith can expect the same results to occur 95 out of 100 times under the same conditions. A difference smaller than the LSD indicates the difference is not statistically significant and the treatment had no effect.

Results and Discussion

Oat yield

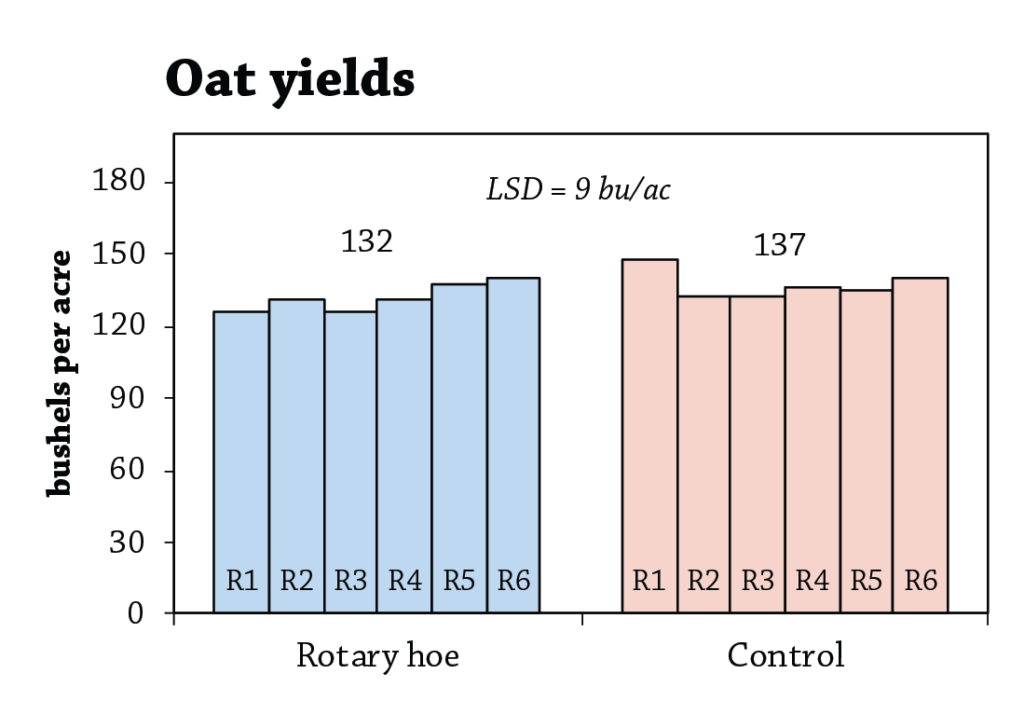

Rotary hoeing oats had no significant effect on oat yield (Figure 1), though it did delay heading by about four days. These results mirror those from on-farm research conducted by Darren Fehr and Dan Wilson with the Iowa Organic Association in 2016.[3] Both farmers saw no difference in oat yields compared to where they did not hoe the oats. In the present trial, Alert and Smith’s average oat yield was 134 bu/ac across the two treatments. That is nearly double the 75 bu/ac average yield for Iowa’s north-central agricultural district in which Alert and Smith farm, for the period 2015–2019.[4]

FIGURE 1. Oat yields at Doug Alert and Margaret Smith’s, harvested on Aug. 8, 2020. Columns represent yields for each individual strip. Above each set of columns is the mean for both treatments. Because the observed difference between the two means (5 bu/ac) is less than the least significant difference (LSD; 9 bu/ac), the results are considered statistically similar at the 95% confidence level.

Economic considerations

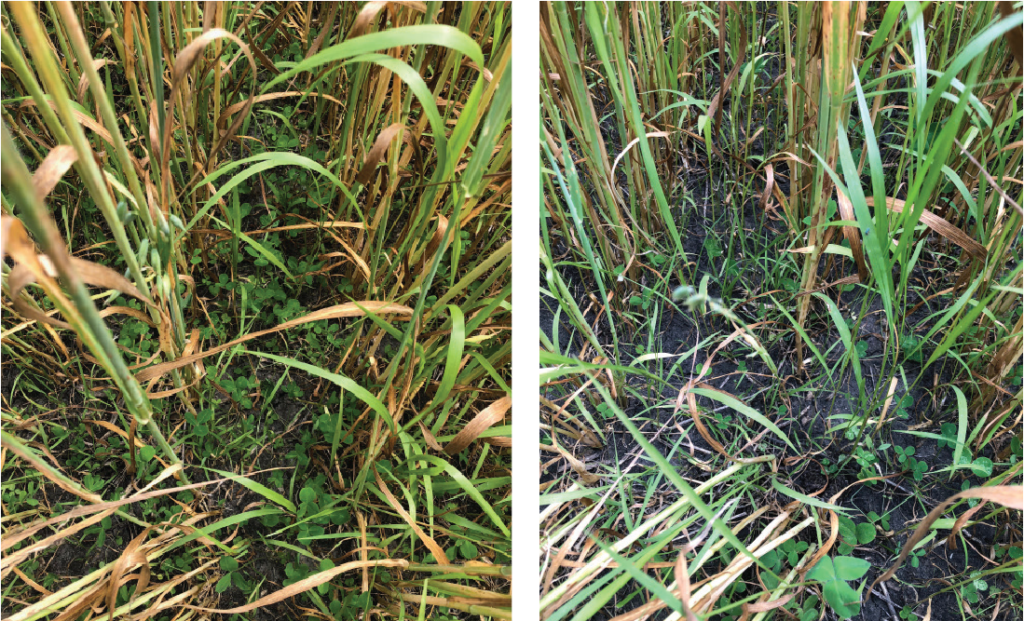

The rotary hoe treatment involved three extra passes through the field compared to the control treatment: two rotary hoe passes (Apr. 26 and May 4) and a broadcast-seeding pass for the red clover (May 4) (Table 1). We assigned costs to the rotary hoe passes ($10.35/ac × 2) and broadcast-seeding pass ($12.10/ac) based on ISU Extension and Outreach survey data for 2020.[5] Ultimately, the rotary hoe treatment cost $32.80/ac more than the control treatment with no improvement in oat yield (Figure 1) nor any reduction in observed weed pressure, according to Alert. He also noted much better red clover establishment with their typical practice of drilling the clover at the same time as the oats (see photos).

At left, red clover that was co-seeded with oats on Apr. 1, 2020. At right, red clover that was seeded with the second rotary hoe pass on May 4, 2020 after oat emergence. Alert and Smith observed much better clover establishment with the co-seeding. Both photos taken on July 13, 2020. Extremely dry weather following oat harvest reduced red clover stands in both treatments by fall.

Conclusions and Next Steps

Because rotary hoeing had no effect on oat yields compared to the control, the practice is considered an added expense to Alert and Smith’s crop production. “Probably not a practice I’ll do again,” Alert said. “It’s more passes and delays clover planting and from experience it works really well to co-seed oats and clover. Though we usually get enough rain to germinate red cover dropped on the soil surface in late April or early May, this really is a riskier option than getting that seed underground with the drill a month earlier.” Smith added: “Our impression is that tine weeding is really only applicable where fields have been clean tilled, with very little or no residue. Rotary hoeing may be an option where weed pressure is very high and/or when a post seeding is planned following oat harvest.” Striving for early oat planting, though, will likely have as much or greater effect on weed suppression than mechanical interventions.

Appendix – Trial Design and Weather Conditions

FIGURE A1. Doug Alert and Margagret Smith’s experimental design. Th ey implemented six replications of the two treatments (12 strips total). Th is design allows for statistical analysis of the results.

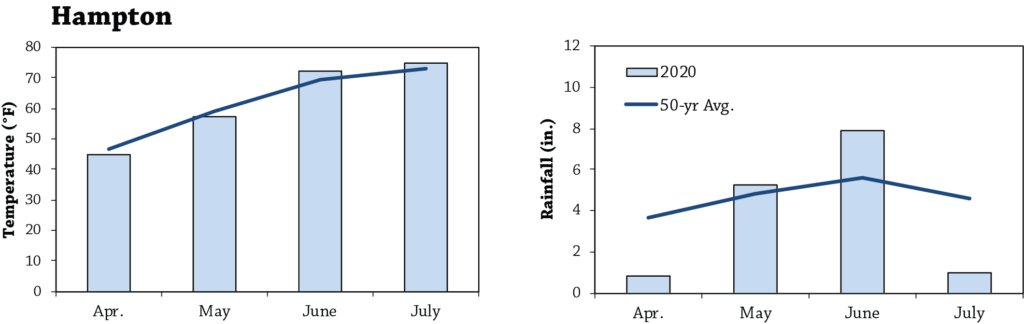

FIGURE A2. Mean monthly temperature and rainfall for Apr. 1, 2020 through July 31, 2020 and the long-term averages at the nearby Hampton weather station.[6]

References

- Lotjonen, T. and H. Mikkola. 2000. Three mechanical weed control techniques in spring cereals. Agricultural and Food Science. 9:269–278. https://journal.fi/afs/article/view/5668 (accessed November 2020).

- Rasmussen, J., H.H. Nielsen and H. Gundersen. 2009. Tolerance and Selectivity of Cereal Species and Cultivars to Postemergence Weed Harrowing. Weed Science. 57:338–345. https://bioone.org/journals/Weed-Science/volume-57/issue-3/WS-08-109.1/Tolerance-and-Selectivity-of-Cereal-Species-and-Cultivars-to-Postemergence/10.1614/WS-08-109.1.short (accessed November 2020).

- Weisberger, D., M.A. Smith, M.H. Wiedenhoeft, D. Fehr and D. Wilson. 2016. Evaluation of Rotary Hoe for Mechanical Weed Control in Organic Oats. Iowa Organic Association. https://www.iowaorganic.org/organic_research (accessed October 2020).

- US Department of Agriculture-National Agricultural Statistics Service. Quick stats. USDA-National Agricultural Statistics Service. https://quickstats.nass.usda.gov/ (accessed October 2020).

- Plastina, A., A. Johanns and O. Massman. 2020. 2020 Iowa Farm Custom Rate Survey. Iowa State University Department of Agronomy. https://www.extension.iastate.edu/agdm/crops/html/a3-10.html (accessed October 2020).

- Iowa Environmental Mesonet. 2020. Climodat Reports. Iowa State University. http://mesonet.agron.iastate.edu/climodat/ (accessed October 2020).