In a Nutshell:

- Vegetable farmers have begun to experiment with living mulches to suppress weeds due to issues sourcing weed-seed free straw and corn stover.

- In this experiment Kate Edwards and Mark Quee compared the use of a living mulch with either rye straw or landscape fabric. Based on previous observations, both farmers hypothesized that pepper yield would be lower where living mulch was planted between rows.

Key Findings

- At both farms, pepper yield (marketable weight) was significantly lower where living mulch was planted between rows.

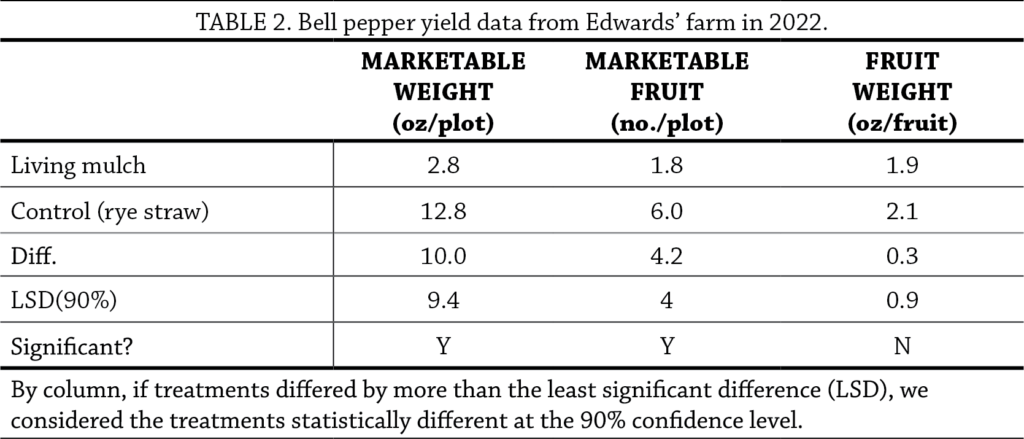

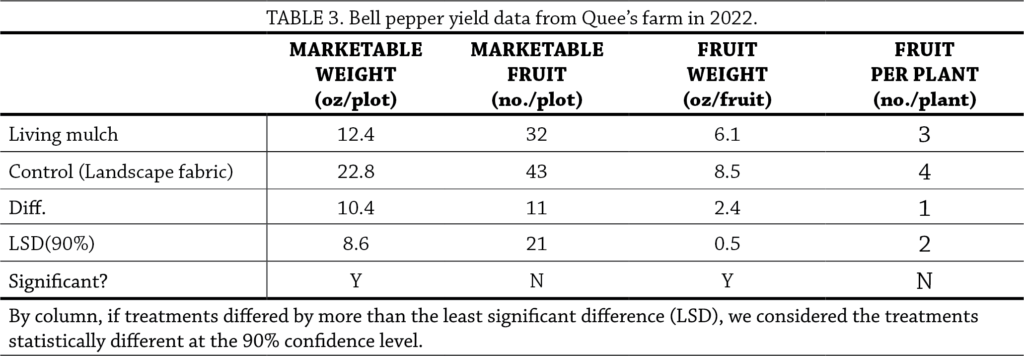

- At Edwards’ farm, yield reductions were related to a reduced number of marketable fruit produced, not fruit weight. At Quee’s farm, the opposite was true. Yield reductions were associated with reduced fruit weight, not the number of fruit produced either per plot or per plant.

Living mulch and landscape fabric are randomized and replicated along a crop row at Mark Quee’s. Photo taken July 17, 2022.

Background

Managing weeds in the area between rows of plasticulture vegetables can be challenging and time-consuming. Mulches, such as straw and corn stover, are often used in these areas to suppress weeds and reduce evaporation. However, weed seeds can be prevalent in these mulch materials. Alternatives such a landscape fabric have been shown to be effective at suppressing weeds but may have higher upfront costs.

Recently, Edwards at Wild Woods Farm has used a living mulch of annual ryegrass and alsike red clover as an alternative to straw or corn stover. A living mulch is a cover crop that grows simultaneously to a cash crop for either part or all the season. Research on living mulches has been conducted in both row- and horticulture-crop systems. Benefits include decreased weed pressure, improved soil health, and reduced labor and herbicide-use.[1,2]

However, because living mulches and cash crops grow simultaneously, competition for water and nutrients can be an issue. The impetus for this on-farm trial came from observations of yield reductions in bell pepper where living mulch was used between rows of plastic. Edwards stated that the goal of this trial would be to, “understand how different type of mulches affect pepper yield in mulches.”

Methods

Design

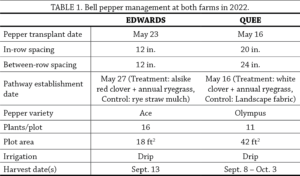

A replicated plot designed was used at both farms to compare the performance of bell pepper under a living mulch treatment or a control (Figure A1). On both farms, peppers were grown using plasticulture. Pepper management, including treatment and control specifics for each farm is presented in Table 1.

Rye straw was applied as the non-living mulch at Kate Edwards’ farm shortly after transplanting peppers. Photo taken May 23, 2022.

Measurements

On both farms, in each plot marketable weight (oz or lb/plot), marketable fruit (no./plot) and fruit weight (oz/fruit) were collected at harvest or summed over several harvests. On Quee’s farm, the average number of fruit produced per plant was also recorded (no. fruit/plant).

Data analysis

To evaluate the response variables listed above, the least significant difference (LSD) was calculated using a t-test. Specifically, this analysis procedure was conducted on marketable weight (oz or lb/plot), marketable fruit (no./plot), and fruit weight (oz/fruit) on both farms and fruit per plant (no. fruit/plant) at Quee’s farm. If the difference in value was greater than or equal to the LSD, the treatment has a statistically significant effect. However, if the difference between the values was less than the LSD the treatments were considered to not have a significant effect on the values. We used a 90% confidence level for the calculations meaning we would expect our findings to occur 9 times out of 10. These statistical calculations could be run because the Edwards’ and Quee’s experimental design included replication and randomization of the living mulch and control (either corn stover mulch or landscape fabric) (Figure A1).

Results and Discussion

On both farms, when comparing living mulch with the control (rye straw and landscape fabric, respectively), marketable weight of bell pepper was lower (Table 1 and Table 2). This suggests that the living mulch is a competitor for water and nutrients. Competition can reduce plant size, limit flower quantity and fruit development at different time points. Data from each farm demonstrate this. Specifically, data from Edwards’ farm show that competition may have reduced fruit number (Table 2), while data from Quee’s farm indicate a reduction in fruit size (Table 3).

Conclusions and Next Steps

Quee noticed clear differences in pepper yields using living mulch between plastic as opposed to landscape fabric. This trial helped answer some of his long-standing questions about the practice. Said Quee, “I’ve toyed with the idea of planting living mulches for years and now I see how their nutrient demands can detract from the cash crop productivity.” The trial also helped to clarify the potential impact of using landscape fabric, “I liked using landscape fabric between rows of plastic. I may do this again.” Edwards was initially interested in using the trial to, “to develop future fertilizer programs for our peppers planted in living mulch.” However, Edwards was clear in the direction that she would take going forward, “We confirmed that we should go back to non-living mulch. And I plan to do so. I have developed a relationship with a farmer who grows [straw] for another friend, and he will grow some for me too”.

For those interested in experimenting with this system, the results suggest that both fertility and water demands would have to be increased to compensate for the presence of the living mulch. Furthermore, both irrigation and fertilization quantities may need to be adjusted based on prevailing heat and precipitation patterns. Differences between pepper yield in living mulch and controls in 2022 may have been exacerbated by lower average rainfall that occurred from July through September (Figure A2).

Appendix – Trial Design and Weather Conditions

FIGURE A1. Edwards’ and Quee’s experimental design consisted of four replications of two treatments (8 experimental units total). This allowed statistical analysis of the results.

FIGURE A2. The monthly average temperature (top) and rainfall (bottom) for the months May through September. The bars are the monthly average for 2022 while the lines are the 50-year monthly average. The data were taken from the Iowa City weather station.[3]

References

- Masiunas, J.B. 1998. Production of Vegetables Using Cover Crop and Living Mulches—A Review. Journal of Vegetable Crop Production. 4. 11–31. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1300/J068v04n01_03 (accessed November 2022).

- Hartwig, N.L. and H.U. Ammon. 2002. 50th Anniversary-Invited Article Cover crops and living mulches. Weed Science. 50. 688–699. http://www.nurserycropscience.info/cultural-practices/cover-crops/technical-pubs/hartwig-ammon-2002-cover-crops-and-living-mulches.pdf (accessed November 2022).

- Iowa Environmental Mesonet. 2022. Climodat Reports. Iowa State University. http://mesonet.agron.iastate.edu/climodat/ (accessed October 2022).