This project was funded by the Walton Family Foundation and Iowa Soybean Association

In a Nutshell:

- Cover crops, primarily cereal rye, are typically seeded in late summer or early fall in corn-soybean production systems in Iowa. Sometimes, however, fall weather conditions prevent seeding activities, cover crop establishment or both. In other instances, farmers are reluctant to seed cereal rye ahead of corn (grass-grass).

- Wade Dooley seeded randomized and replicated strips of oats and fava beans in early spring to determine any effect on corn yield.

- Jeremy Gustafson conducted a demonstration in which he seeded cereal rye in early spring and then either terminated the rye when he planted soybeans or allowed the rye to grow with the soybeans until early July.

Key Findings:

- Corn yields were not affected by the cover crops at Dooley’s farm.

Methods

Dooley

To test the effect of the spring-seeded cover crops on corn yield, Dooley compared three treatments:

- Oats

- Fava beans

- No-cover-crop (control)

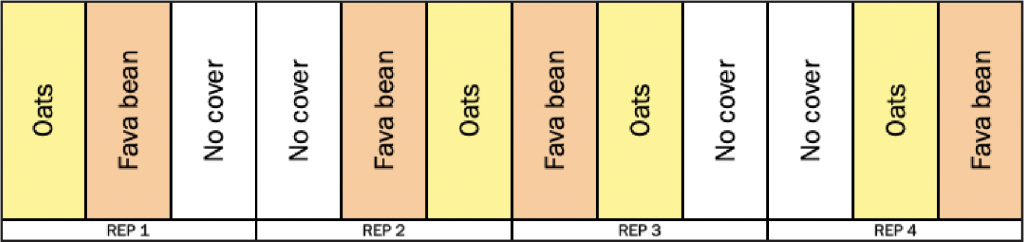

Dooley implemented four replications of the three treatments in randomized strips (Figure A1). Strips were 30 ft wide and 760 ft long. Dooley seeded the oats (60 lb/ac) and fava beans (70 lb/ac) with a grain drill on Apr. 16. He plugged drill openers to create no-cover skip zones to plant corn into (30-in. centers). After terminating the cover crops on May 23, Dooley planted corn on June 3 at a population of 36,000 seeds/ac in 30-in. row-widths. Dooley applied 71 lb N/ac as UAN(32) with the planter and sidedressed an additional 76 lb N/ac as UAN(32) on July 16. Corn was harvested on Dec. 12 and corrected to 15.5% moisture.

Wade Dooley seeded strips of oats and fava beans on Apr. 14, about six weeks before he planted soybeans on June 3.

To rank the effects on corn yield of the spring cover crop treatments Dooley compared, we calculated Tukey’s least significant difference (LSD). We assigned different rankings to the treatments if the difference resulting from any two treatments was greater than or equal to the LSD – we also refer to this as a statistically significant effect. On the other hand, if the difference resulting from any two treatments was less than the LSD, we consider the treatments to be statistically similar (those two treatments received the same ranking). We used a 95% confidence level to calculate the LSDs, which means that we would expect our rankings to occur 95 times out of 100. We could make these statistical calculations because Dooley’s experimental design involved replication and randomization of the three treatments (Figure A1).

Gustafson

Gustafson seeded cereal rye (40 lb/ac) in 10-in. row-widths on Apr. 14. He terminated half the rye the same day he planted soybeans (June 3) and terminated the other half about one month later (July 1). Gustafson left a single check strip where he did not seed cereal rye. He planted soybeans to the entire field on June 3 at a population of 140,000 seeds/ac in 30-in. row-widths. Soybeans were harvested on Oct. 10 and corrected to 13% moisture.

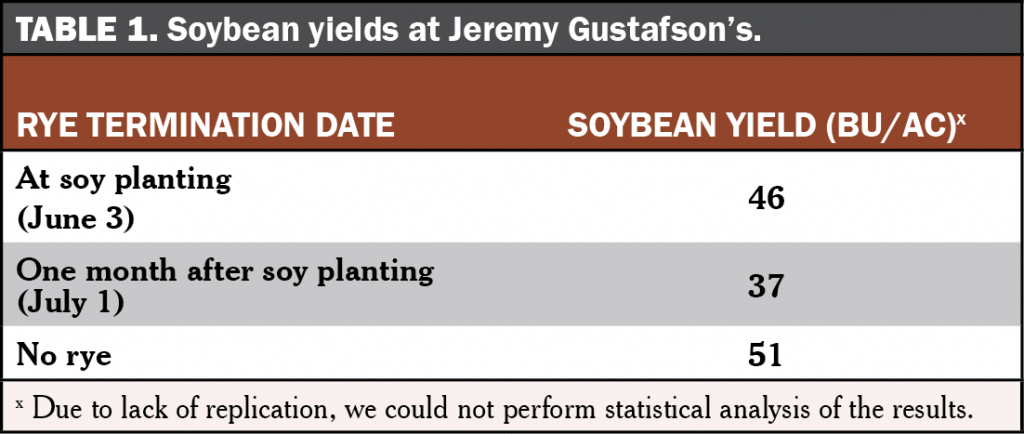

We could not perform statistical analysis of results at Gustafson’s because treatments were not replicated.

Spring-seeded cereal rye cover crop at Jeremy Gustafson’s on June 6. At right, rye was terminated on June 3. At left, rye that has yet to be terminated. Photo credit: Theo Gunther, Iowa Soybean Association.

Results and Discussion

Dooley

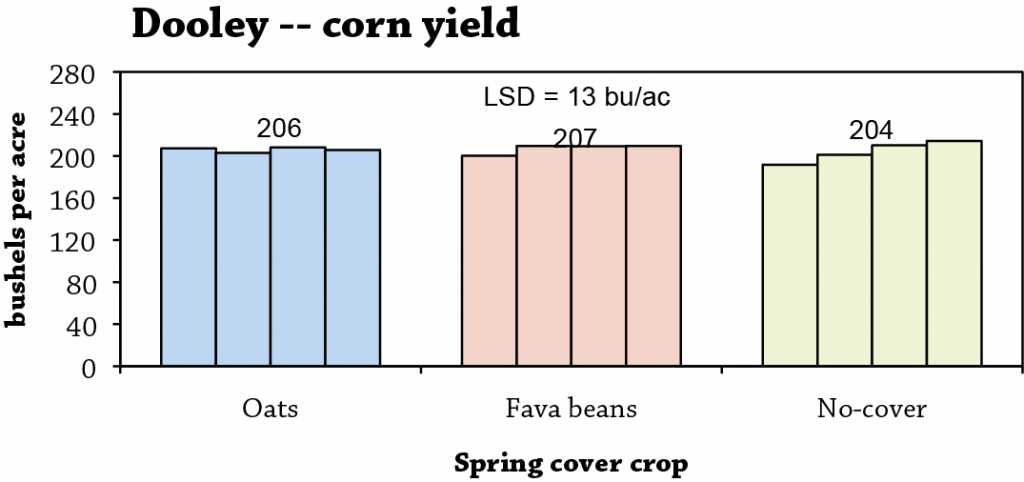

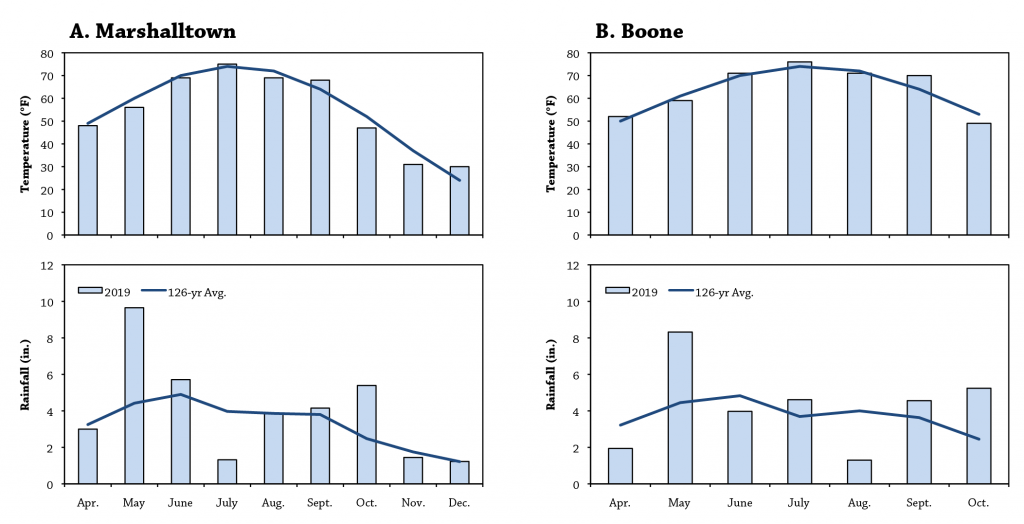

Compared to the no-cover-crop control, neither the oats nor the fava beans had any effect on corn yield at Dooley’s (Figure 1). Dooley noted less than 100 lb/ac of biomass for either cover crop. He attributed the low amount of cover crop growth to an unusually cool and wet spring (Figure A2). As such, he was not surprised by the lack of effect on corn yields. Across treatments, mean corn yield at Dooley’s was 206 bu/ac which was below the five-year Marshall County average of 215 bu/ac.[1]

FIGURE 1. Corn yields at Wade Dooley’s. Columns represent individual strip values. Above each set of columns is the treatment mean. Because the difference between the treatment means is less than the least significant difference (LSD), the treatments are considered statistically similar at the 95% confidence level.

Gustafson

While we could not perform statistical analysis at Gustafson’s, it does appear that allowing the spring-seeded cereal rye to grow with the soybeans until July reduced yield (Table 1).

Conclusions and Next Steps

Seeding cover crops in the spring may be a way for farmers to compensate for not being able to get a cover crop seeded the previous fall. It may also allow for seeding cover crops that are atypical of corn-soybean systems in Iowa (e.g., Wade Dooley seeding fava beans in this project). Whether this practice can be beneficial to cash crop production, however, remains to be seen. Certainly any cover crop growth in the early spring is better than no growth (bare ground) when it comes to preventing soil erosion and reducing nutrient loss. Future studies may investigate the ability of spring-seeded cover crops to mitigate weed pressure.

Appendix – Trial Design and Weather Conditions

Figure A1. Experimental design used by Wade Dooley. The design included randomized replications of the treatments. This design allowed for statistical analysis of the results.

Figure A2. Mean monthly temperature and rainfall and the long-term averages at the nearest weather stations to each farm.[3] A) Marshalltown (Dooley); B) Boone (Gustafson).

References

- US Department of Agriculture-National Agricultural Statistics Service. Quick stats. USDA-National Agricultural Statistics Service. https://quickstats.nass.usda.gov/ (accessed January 2020).

- Gailans, S. and L. Juchems. 2019. Winter Cereal Rye Cover Crop Effect on Cash Crop Yield. Practical Farmers of Iowa Cooperators’ Program and Iowa Learning Farms. https://practicalfarmers.org/research/winter-cereal-rye-cover-crop-effect-on-cash-crop-yield-4/ (accessed January 2020).

- Iowa Environmental Mesonet. 2019. Climodat Reports. Iowa State University. http://mesonet.agron.iastate.edu/climodat/ (accessed January 2020).