Grazing Rates: What Is a Fair Payment?

Father and son team, Jon and Jared Luhman, contract graze their cattle through the winter on cover crops and crop residue. Their goal in each arrangement is to establish grazing rates that benefit both the landowner and themselves. The Luhmans operate Dry Creek Red Angus near Goodhue, Minnesota, raising Red Angus and Hereford cattle for grass-finished beef, and the contract grazing arrangement they follow is one of four common types of grazing agreements used when land and livestock are owned by different people.

Contract grazing, when carried out thoughtfully, has many benefits for people and the land. Well-managed cropland and pastures have less nutrient runoff and erosion, contributing to cleaner water and healthier wildlife habitats. These grazing arrangements can also benefit people. Contract grazing can foster a more deeply rooted, diverse agriculture community. It also opens the door for young and beginning farmers to own a livestock enterprise without owning land, and can provide established livestock operations with more forage options and flexibility during weather events – like drought.

With the advent of the Midwest Grazing Exchange and the “Livestock on the Land” campaign, PFI has been promoting contract grazing (also known as custom grazing) as a way to enrich the Midwestern landscape through more integrated systems. The practice can help graziers increase their forage availability and keep animals in ideal body condition longer into the year. And landowners can use grazing to keep or import fertility to their land, benefit soil health and generate added revenue.

Types of Arrangements

This extra promotion has led to questions about the rates to charge for grazing arrangements. Rates depend on the grazing arrangement. Depending on the operation type and available resources, the agreement you choose may vary and could affect the rates charged. The most common types of agreements are:

- Pasture rent: Pasture is rented at a per-acre, monthly or daily rate. Pasture cash rental rates can be found in Iowa State University’s “Cash Rental Rates for Iowa 2021 Survey.” 2021 rental rates for improved permanent pasture range from $69-$98 per acre per year, depending on your district.

- Contract grazing: A flat rate is paid per animal per month or per day by the livestock owner to the landowner. This can be applied to all classes of livestock.

- Per pound of gain: These incentive-based agreements pay based on average daily gain or milk production per day or per grazing season.

- Resource sharing: Resources the livestock owner and landowner contribute are itemized. Every change in contribution (resource) changes how the profit is split.

Determine Your Rate

To decide on a fair grazing rate, all parties need to understand the costs they’ll incur for entering into the grazing arrangement. For landowners, costs could relate to the value of the land or crop that will be grazed, or to infrastructure that will be needed, such as fencing or watering. For the livestock owner, costs could include the amount of labor that will be required or whether extra services will be provided, like herd management or supplemental feeding.

Consider these questions when determining your rates:

- What is the value of the land or crop being grazed?

- What is the amount of labor and additional services being provided?

- What type of livestock are being grazed?

To inform their grazing agreements, the Luhmans use the “cow day” unit, a figure expressing what it takes to feed one average cow in the herd per day. They also compare the costs of different feedstuffs available to them – crop residue, sorghum sudangrass and hay – to ensure they are taking the most economical feeding route from late fall through early spring.

“The rates we worked out we felt would generate an added profit for [the landowner] and for us,” Jared says. The Luhmans’s strategy is to graze crop residue until it’s buried or gone, then move to grazing sorghum-sudangrass pasture and supplementing with hay bale grazing as needed. They priced out their grazing costs as follows: grazing corn residue cost $0.50 per cow day, grazing sorghum-sudangrass cost $1.60 per cow day and hay bale grazing cost $2 per cow day.

To determine the rates, they estimate expenses (input costs per acre) for the farmer. The 2020-2021 input costs included $208 for haying (seeding, planting and harvesting), $69 for sorghum-sudangrass (seed and planting) and $200 for land rent, totaling $477 per acre owed to the landowner. Jon and Jared then incorporated their desired income and decided to charge $1.60 per day for grazing sorghum and $2 per day for bale grazing, totaling $536 per acre owed to the Luhmans.

Taking the grazing revenue of $536 per acre and subtracting the input costs of $477 per acre resulted in a $59 profit per acre for the landowner. The Luhmans were not paid in this transaction. But through careful planning and weighing the price of different forage options, they saved over $1 per day compared to only grazing their own pasture and supplementing with hay through the rest of the grazing season.

Revenue

- Sorghum Grazing: $1.60 x 170 cow days per acre = $272

- Hay Bale Grazing: $2 x 132 cow days per acre = $264

- Grazing + Hay Feeding = $272 + $264 = $536 per acre

Grazing Revenue of $536 – Input Costs of $477 = $59 profit per acre for the landowner.

“Our hope was that this would be advantageous for both of us and that [our landowner] would get to keep all of that fertility on his land, build soil, get animal impact on his land and break up his crop rotation and generate a $59 rate of return to those expenses,” Jared says.

When all contracted parties know their input expenses, everyone will know what rates need to be charged for mutual profitability.

Additional Rate Formulas

Because livestock and land enterprises vary, so can these calculation rates. Another example, listed in ATTRA’s “Grazing Contracts for Livestock” publication, comes from Kevin Fulton, a custom grazier in Litchfield, Nebraska. He uses a formula that includes all costs associated with grazing: (weight of the animal) x (forage intake) x (forage price) + daily management fee = daily grazing fee. This fee structure can easily be adjusted based on animal gain and billed on a monthly basis. If setting the price based on animal gain, it’s important to know the livestock you’re receiving are built for gaining on pasture.

Other contracts may be primarily based on husbandry fees and reimbursements. A sample grazing custom grazing contract from Meg Grzeskiewicz of Rhinestone Cattle Consulting, based in Colden, New York, chooses rates based on this method. In her contract, the livestock owner pays the experienced grazier a husbandry fee of $1.25 per animals per day when no hay is fed, and $1 per animal per day when hay is fed. The livestock owner is also responsible for reimbursing direct expenses like hay, transport, minerals, vet bills and breeding expenses.

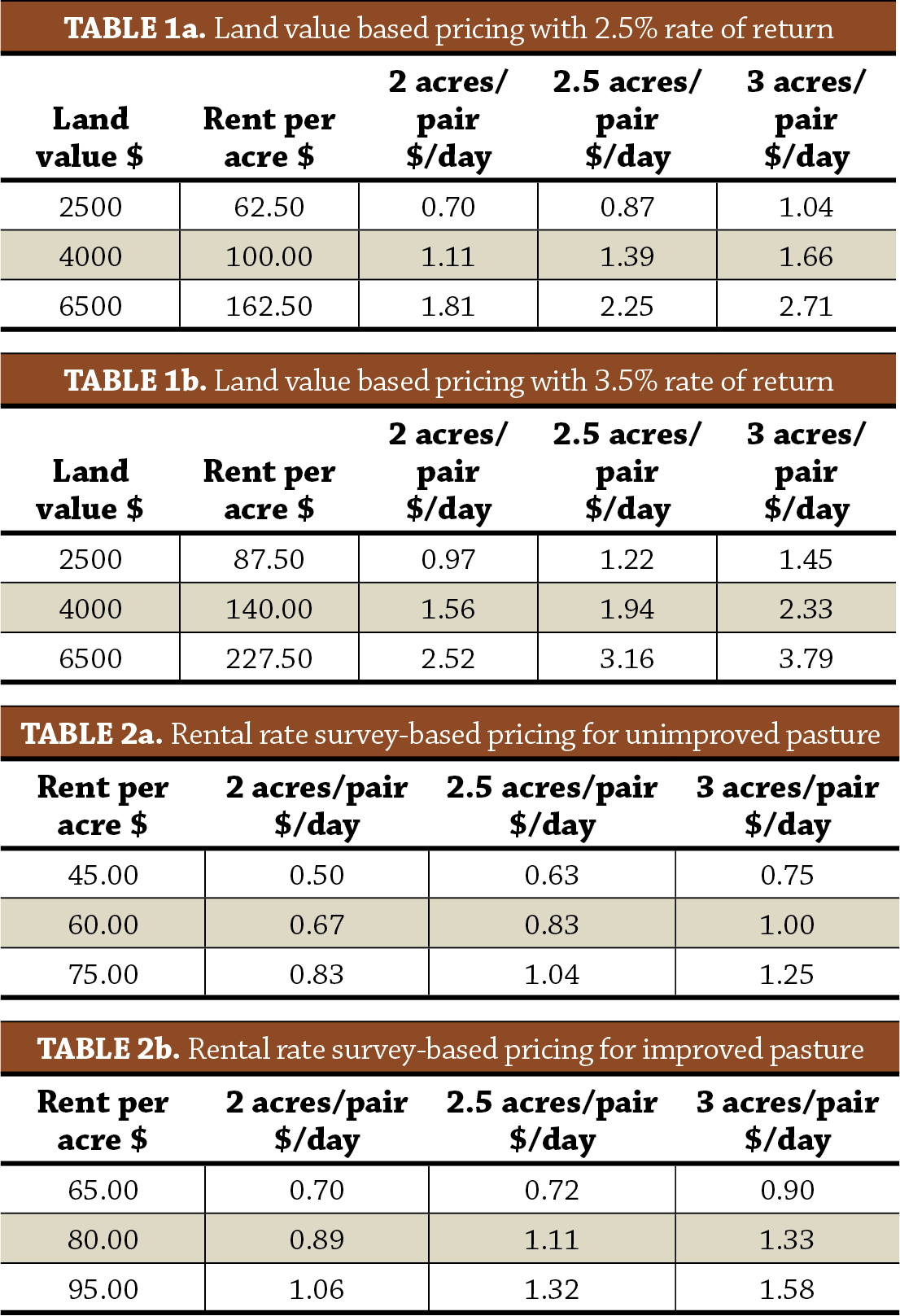

Some landowners may choose to determine grazing rates based on land value or rate of return. The Iowa Beef Center published land value-based pricing and rental rate survey-based pricing in 2017 (see Tables 1a–2b). These rates assume a grazing season of 180 days.

When Grazing Small Ruminants

Rates for contract grazing small ruminants like goats or sheep can differ greatly from cattle. When charging for targeted grazing – the practice of using livestock for specific vegetation management – it’s important to consider the size of the area to be grazed, how much vegetation needs to be grazed, location and distance of the grazing site and the amount of labor needed for herd oversight and temporary fence movement.

“It’s important to remember that contract grazing sheep and goats for vegetation management is different than rotationally grazing cattle,” says Margaret Chamas, a lifetime PFI member who raises goats, sheep, cattle and poultry at Storm Dancer Farm near Smithfield, Missouri, and is a Goats on the Go affiliate. “With vegetation management, I want to damage the vegetation.”

Margaret grazes her goats on a per-acre rate determined on a case-by-case basis depending on vegetation thickness, time, water sourcing, fence and labor required. She also charges a minimum fee to all her clients for transporting her goats to the grazing sites. With each job, Margaret’s aim with the grazing agreement is to ensure all parties understand the expectation for the site and the grazing rate based on the site’s unique characteristics, as well as what investments will be made.

“My goal,” she says, “is for the customer to know how much the job will cost before it begins.”