We Are Each Other’s Harvest

Representation matters to bring along the next generation of Black Iowan farmers and growers.

In 2018, a report from 24/7 Wall St., an independent financial news and commentary website, ranked the Waterloo-Cedar Falls metro as the No. 1 worst metropolitan area in the country for Black Americans. The report bases its analysis on racial gaps in several socioeconomic indicators, such as income, unemployment, homeownership and more. In the latest report from 2020, the metro was no longer first, but still ranked as the fifth worst metro area for Black Americans.

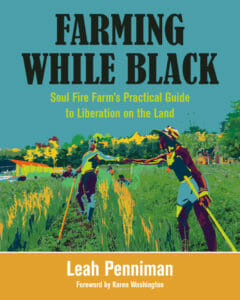

“Owning our own land, growing our own food, educating our own youth, participating in our own health care and justice systems – these are the sources of real power and dignity.”

– Leah Penniman, from “Farming While Black”

With 16% of Waterloo’s population identifying as Black, the city has the highest percentage of Black residents of any community in Iowa. This demographic traces back to the Illinois Central Railroad’s efforts in 1910 to break a strike of local white union members by recruiting Black strikebreakers from the Deep South, specifically Mississippi. As Waterloo’s industry expanded through the 20th century from railroads to companies like Rath and John Deere, the Black population grew along with the city.

Beckoned by the Promise of Opportunity

The railroad is what brought DaQuan Campbell’s grandmother, Lenora Newman, from Durant, Mississippi, to Waterloo. Her parents were sharecroppers, an unfair system that emerged in the South at the end of the Civil War. In exchange for a share of the crop, Black sharecroppers were able to farm small plots of land. But with few resources or little to no capital, their debt to landowners compounded year after year with no way to repay it. To survive, growing their own food was essential. When Lenora moved North, she brought a belief in self-reliance with her.

“I really became exposed to growing food from my grandmother,” says DaQuan, a Waterloo native. He is also a beginning farmer, manager of the Waterloo Urban Farmers market and founder of We Arose Co-op, which is dedicated to getting fresh produce to members of the community who lack access.

“My grandparents instilled in me the importance of growing your own food and how food brings families together. From that upbringing, my grandmother took those teachings with her when she migrated to Waterloo with her brother and sisters to work on the railroads. For as long as I can remember, she always had a garden and appreciated the fact we could have a meal from the food in our backyard.”

“My vision for We Arose Co-op started with me wanting to help both market and non-market producers diversify their distribution channels while providing an outlet to bring fresh produce to underserved areas. I also wanted to make produce affordable for the community, building a bridge between the two.”- DaQuan Campbell

Shaffer Ridgeway likewise moved to Iowa from the South – in his case, from Alabama in 2000 to work as a soil conservationist for the Natural Resources Conservation Service. Having interned for the agency during high school and college, he began to work for NRCS full-time after graduating from his alma mater, Alabama Agricultural and Mechanical University, a historically Black land-grant university in Normal, Alabama. He has been in Iowa ever since.

Practicing What You Preach

As a district conservationist for Black Hawk County, Shaffer supports farmers in his county by educating them on the various NRCS programs and funding opportunities. After many years advising farmers how to implement conservation practices on their farms, he began to think about putting some of those same practices to work outside his job. His initial idea was to install a test plot that would let him try soil health practices – but he quickly realized he needed a way to pay for the idea.

“So, then I thought, I’ll grow vegetables to pay for it,” Shaffer says. “It’s one thing to see something on paper, or see the change on the landscape, and a whole other to put it into practice yourself. I wanted to practice what I have been preaching to farmers.”

In 2019, Shaffer and his wife, Madelyn, established their farm, with an emphasis on growing Southern vegetables for Midwesterners. Acknowledging that aim, Shaffer and Madelyn named their farm Southern Goods. “My wife came up with that name,” Shaffer says. “There were already a few folks in the community growing these types of crops – for example, purple hulled peas. Others were growing peas on a garden scale of about 5 or 6 bushels, whereas I wanted to be able to grow and market about 50 to 100 bushels of peas.”

Shaffer’s original idea of testing soil health practices quickly transitioned into a vision that was greater than himself. As he experimented with vegetable varieties, he felt increasingly pulled to make an impact in his community – the Black community, which comprises 75% of his customer base. “In the Black community, 40% of folks live with at least two chronic diseases, which I believe ties back to our food,” Shaffer says.

Soon, Shaffer’s path would intersect with that of DaQuan’s. Having learned about each other through mutual friends, both DaQuan and Shaffer connected as growers with a strong desire to serve the community.

“There are so many small things that go into trying to develop a successful farm. Having someone who looks like you, and can relate to you, allows you to feel like you are in a safe place to communicate.” – DaQuan Campbell

“I began to take interest in hearing Shaffer talk about the ideas he had for his farm and learning how they aligned with my growing practices,” DaQuan says. “To hear how passionate and focused he is not just growing vegetables, but growing quality food based on developing healthy soil. We just hit it off.”

Healthy Soil, Healthy Food, Healthy People

In 2020, as Shaffer was developing and expanding Southern Goods, DaQuan worked to recruit him to be a vendor at the Waterloo Urban Farmers Market, where he serves as market manager. In that role, DaQuan observed that many growers were relying solely on the farmers market as their main distribution channel – a situation that stokes competition and makes it hard for producers to collaborate. He saw there was demand to create an additional market opportunity, and in 2021 launched We Arose Co-op to bring growers together while navigating ways to bring fresh food to the community.

“My vision for We Arose Co-op started with me wanting to help both market and non-market producers diversify their distribution channels while providing an outlet to bring fresh produce to underserved areas,” DaQuan says. “I also wanted to make produce affordable for the community, building a bridge between the two.”

DaQuan wanted to situate the co-op in the neighborhood he was raised in, Waterloo’s 4th Ward, which he says has “way more convenience and liquor stores around than grocery stores.” According to 2019 data from the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Food Research Atlas, the most recent data available, several Waterloo neighborhoods are considered food deserts, based on criteria that includes a poverty rate higher than 20% and one-third of the population living more than 1 mile from a supermarket or large grocery store.

Farmers DaQuan recruited to market through the co-op supported his goal of directly addressing this gap in access to local food. Shaffer became one of the co-op’s local producers. “Our vision of trying to grow something bigger than ourselves is what gets me excited to work with DaQuan,” Shaffer says. “My relationship with the co-op helps me fulfill my business goals by providing fresh food to historically underserved communities, and by getting young people out on the farm and showing them how we grow food.”

Crew members, comprising students from University of Northern Iowa and youth in the Waterloo community, can work with the co-op through its Greens to Go food delivery program.

Youth farm crew members harvesting produce for We Arose Co-op with Shaffer Ridgeway (center) and DaQuan Campbell (right) at Southern Goods Farm in Waterloo, Iowa.

Southern Goods Farm’s 3 acres of vegetable production include sweet potatoes, tomatoes and cabbages, pictured here. Additional produce includes purple peas, pumpkins, collards, okra and other crops popular in the Southern U.S.

Each One, Teach One

In “Farming While Black,” Leah Penniman shares how Black people coming together and sharing knowledge within the Black community exhibits powerful resilience. “‘Each one, teach one,’ is one of our people’s proverbs,” she writes in the book. “During slavery, Black people were denied education, so when someone learned how to read, it became their duty to teach someone else. That duty persists.”

In “Farming While Black,” Leah Penniman shares how Black people coming together and sharing knowledge within the Black community exhibits powerful resilience. “‘Each one, teach one,’ is one of our people’s proverbs,” she writes in the book. “During slavery, Black people were denied education, so when someone learned how to read, it became their duty to teach someone else. That duty persists.”

Shaffer acknowledges this principle. “We’ve all come up on the shoulders of people who’ve gone before us, people who figured out how to navigate the system. Not beat the system, just navigate the system.”

Representation matters. Shaffer has a saying that he shares with his sons: “You can never be what you have never seen.” As a Black man who has worked within the agricultural system for over 20 years, he tries to help people navigate the system whenever possible.

“There are so many small things that go into trying to develop a successful farm,” DaQuan says. “Having someone who looks like you, and can relate to you, allows you to feel like you are in a safe place to communicate. Shaffer’s experience working with other farmers – and his perspective as a farmer himself, passing on that knowledge to me and others – is something I cherish. Having someone like Shaffer to call and discuss the small things makes all the difference in the world.”

Cloud of Witnesses

Together, Shaffer and DaQuan are fulfilling each other’s goals of providing local food to Waterloo’s historically underserved communities, while also exposing Black youth to agriculture through their farms. “What I am most proud of is the opportunity to shift the perception of the youth on the importance of growing food and maintaining a healthy lifestyle,” DaQuan says. “Our mission for We Arose Co-op is to inspire future generations to nourish themselves, their families and communities.”

DaQuan’s family carries excitement and pride at being able to witness his grandparents’ teachings unfolding about the power of growing your own food. “My 87-year-old grandmother will wake me up asking, am I ‘ready to go to the field?’ It is amazing how motivated she is to help me see the farm through. I’m just happy that I made them proud and continue to make them proud.”

For Shaffer, while both of his parents died before he started Southern Goods, he says his vision for the farm stems from them.

“Our vision of trying to grow something bigger than ourselves is what gets me excited to work with DaQuan. My relationship with the co-op helps me fulfill my business goals by providing fresh food to historically underserved communities, and by getting young people out on the farm and showing them how we grow food.”- Shaffer Ridgeway

“My dad was an entrepreneur who had a small farm, while my mom was very community-driven, always thinking about how to help other people,” Shaffer says. “I personally feel that they are part of what is guiding me. There is a scripture that talks about the great cloud of witnesses, and I feel like they are part of that great cloud of witnesses cheering me on.”