Oats Bearing Profits: Cutting Inputs by Extending Crop Rotations

It’s no secret that in most years, a corn crop will bring in more revenue than a small grain crop. So how do rotations that include a small grain make more money than simple corn-soybean rotations? The answer is in the inputs.

Nebraska farmer Jeff Steffen has used an extended rotation since 2015. Jeff and his wife Jolene operate a 600-acre farm in the most northeast portion of the state and they raise oats for cover crop seed, in addition to corn, soybeans, rye and peas. On our January 2022 Shared Learning Call, Jeff delved into the details of his five-year rotation of corn, soybeans and oats and the economics that support his decision to operate with extended rotations.

Breaking the rotation

“There is no set rule to extending the rotation,” Jeff says, “but my goal is to get two or more years break from a crop”. Jeff uses no-till and in the last 10 years became interested in finding more ways to reduce soil runoff, improve overall soil health and increase farm profitability. From 2015-2019, Jeff grew a five-year rotation of corn-soybeans-oats-soybeans-corn and subsequently analyzed his budgets across this rotation. He used templates from the University of Nebraska as a baseline and then worked with his crop advisor to ensure cost and yield estimates were accurate for his region and soil type. On average, his budgets showed that across the five years he was able to achieve an average net profit of $202 per acre per year. These profits included the cost of land but excluded government subsidies.

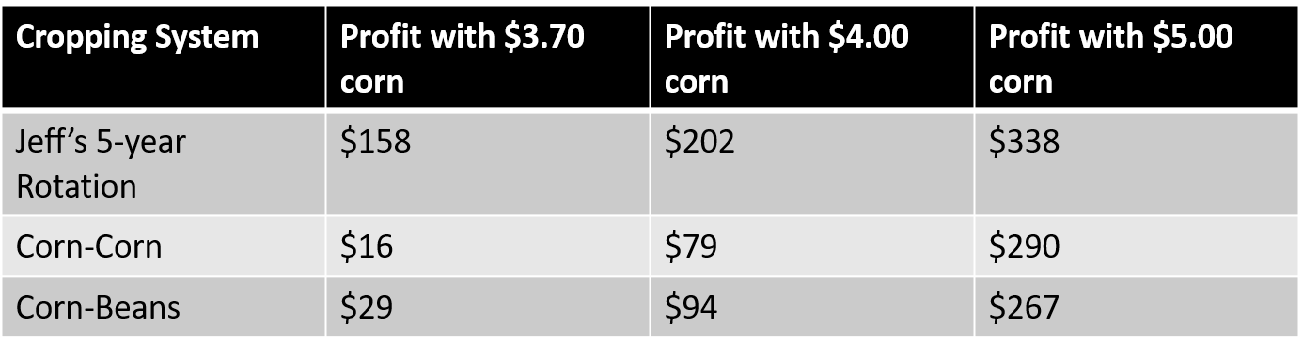

Jeff found that profitability in his extended five-year rotation on average exceeded corn-corn and corn-soybeans rotation profits by up to $142 per acre per year, even across different corn pricing scenarios (see Table 1). “Even with $5 corn, the rotation with oats still produced more dollars per acre if you looked at it as a five-year system,” Jeff says. Corn did generate the most revenue on a yearly basis throughout the rotation, but as Jeff notes, “there’s no way I could reduce my inputs on corn without oats in the rotation.”

Table 1: Profits per acre per year by cropping system with adjusted per bushel corn prices from 2014-2019. Soybean price was figured as 2.5 times the price of corn.

Jeff has a steady market for his oats – he conditions the grain and sells it as certified seed with good profits. So he was curious to see how the extended rotation would perform under different small grain pricing scenarios as well. “Let’s say one in five years you grow a small grain crop that only breaks even” Jeff says. “You still have more profitability compared to corn-corn or corn-soybean rotations.”

What matters is the break in the rotation. Even with a three-year system, which Jeff didn’t closely analyze, he speculates “you would probably pick up more efficiency with a third of your rotation in small grains.”

Jeff advises fellow farmers to “be true to your own numbers.” Hearing noise in the farming community about what is the most profitable as opposed to learning for himself is what makes Jeff’s enterprise a success.

Savings snowball

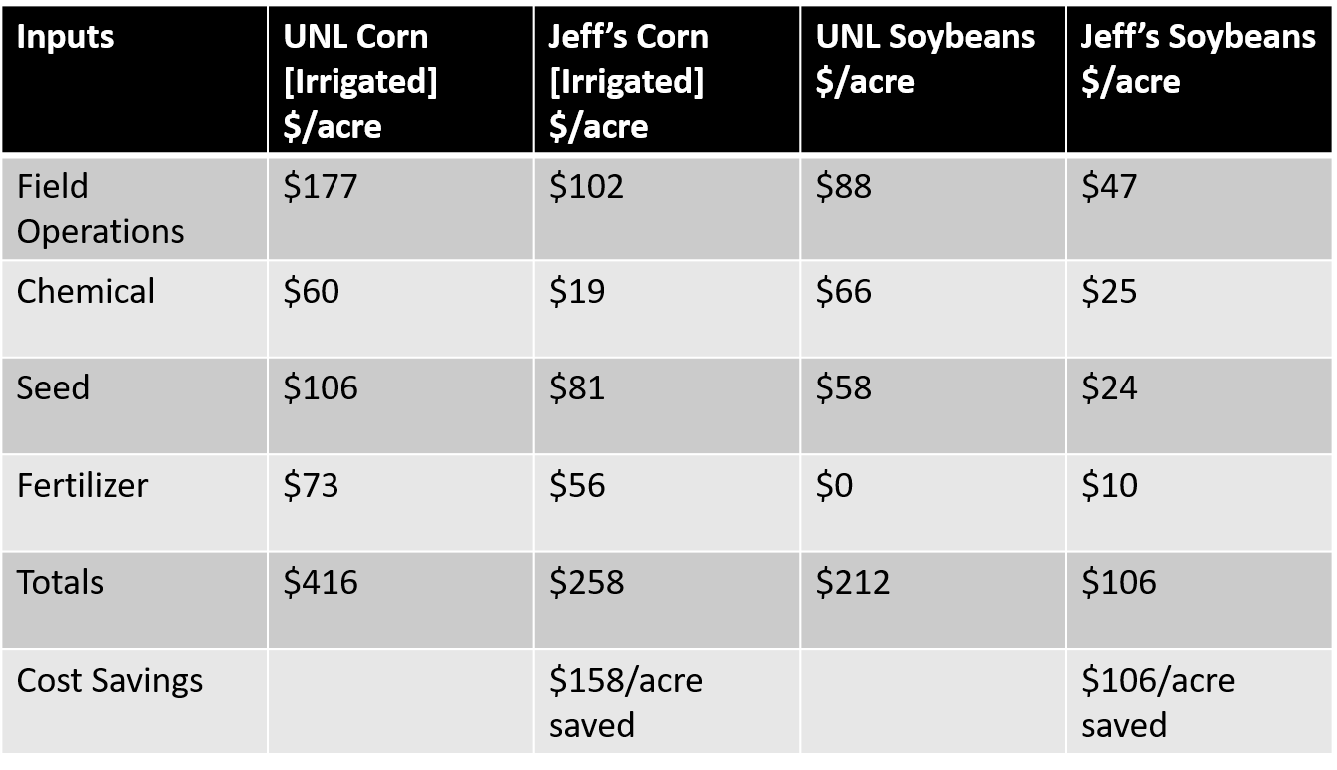

The increased profits Jeff sees can be traced to a decline in inputs used in his corn and soybeans. “For corn, I was generally saving $160 per acre on inputs and for soybeans I was saving $106 per acre,” Jeff says (see Table 2). “Once you see the benefits and how the rotation reduces your inputs, you really get on board.”

“Your seed, chemical and fertilizer are the big three,” says Jeff. Jeff has ceased using expensive seed treatments, and he also notes, “I’m not seeing an advantage to the traits anymore.” He hasn’t used any insecticides since 2011 and he’s been able to cut back on his herbicide use as well by cutting a post-emerge treatment in corn and foregoing RoundUp in soybeans in certain years, saving him up to $40 per acre for a given crop. Jeff cuts down on fertilizer costs by adding legume cover crops after his oats. “I grew a lot of fertility in cover crops after my small grain in 2021 and I could see a savings of $100 per acre in nitrogen this year alone.”

Looking ahead to 2022, Jeff notes, “the profit advantage is going to be substantially more with the increase in input prices.” By being attentive to how a crop is doing by testing fertility, keeping records and making informed decisions by “viewing everything as an economic threshold” Jeff has seen elevated profitability.

Table 2. Input Costs Per Acre over the five-year rotation as compared to University of Nebraska Lincoln’s suggested cost figures for corn and soybeans.

To achieve optimum soil health benefits Jeff moved to harvesting just the heads of the oats and leaving straw behind to build organic matter in the soil. Jeff estimates “you easily need to spend $50 a ton to cover the nutrients of straw.” In addition to helping Jeff save costs on fertilizer, leaving the oat straw behind better allows his summer cover crop to germinate, while also providing ground cover for weed control.

Added income with livestock

On top of the savings he sees by cutting inputs, Jeff gains additional revenue through grazing livestock. Jeff sows cover crops through the entirety of his five-year rotation and attests, “your reduced inputs of a five-year soil health system of incorporating cover crops is always going to be more profitable.” Following oats, his summer cover crop contains species like sunflowers, buckwheat, cowpeas and sun hemp, which fix nitrogen and can be grazed. Jeff charges below market at $0.35-$0.50 per day to graze his residue and cover crops for his family operation. The price varies based on the quality of the cover crop. This price also helps his nephew, who owns the cattle. The average price to graze pasture in Northeast Nebraska is typically $2 per day.

Jeff notes that maximum benefit can be gained from extended rotation residue and cover crops when farmers use their own cattle to graze. “Cattle do not just maintain on the cover crop; they gain weight” states Jeff. Having that on-farm feed source would provide economic benefit above and beyond what the extended rotation generates on its own.

Other small grains may be used in place of oats to achieve levels of profitability. Jeff notes, “any small grain is going to give you these benefits – say 1 in 5 years or 1 in 3 years.” Alternative options include hybrid rye, winter wheat and spring peas, whichever works best for your environment and local markets.

To access more information about small grains consider signing up for our monthly small grains newsletter and find out when to tune into future shared learning calls via zoom.