This project was funded by the Walton Family Foundation

In a Nutshell:

- Based on previous on-farm research he has conducted,[1] Sam Bennett has seen evidence that a cereal rye cover crop can suppress weeds and reduce herbicide inputs in soybeans. As such, he grew soybeans following a cereal rye cover crop and compared three herbicide packages that varied in residual activity and cost.

- Bennett hypothesized that weed control and soybean yield would not be sacrificed by reducing herbicides, provided adequate cover crop growth in the spring before seeding the soybeans. “I hope that we can reduce our herbicide use and cost by enough to cover the costs of establishing the cover crop. We’re always trying to answer the question of how to make covers pay for themselves,” Bennett said.

Key Findings:

- Bennett recorded similar soybean yields between the low-cost and full (most expensive) herbicide packages he compared.

- The low-cost herbicide package improved returns on investment by $16.08/ac compared to the full package owing to reduced costs associated with the low-cost package.

Sam Bennett: “The more I learn that I can rely on the cereal rye cover crop for weed suppression, the more I can work to reduce my herbicide plans.”

Methods

Design

Bennett seeded a cereal rye cover crop on Sept. 12, 2018 at a rate of 45 lb/ac to standing corn using a high-clearance seeder. On May 11, 2019, Bennett planted soybeans to the entire field at a population of 140,000 seeds/ac in 15-in. row-widths. Six days later, on May 17, he terminated the cover crop.

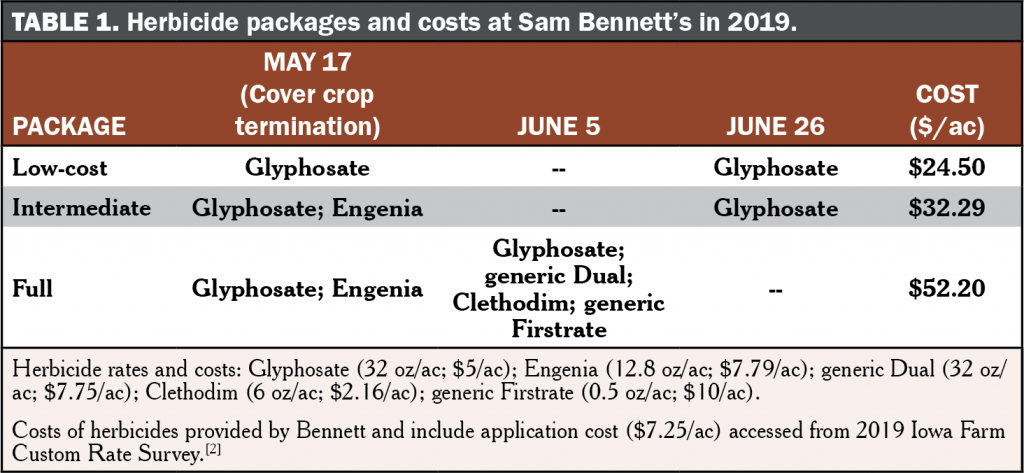

To test whether he could reduce herbicide use, Bennett compared three packages that ranged in residual activity and cost (Table 1).

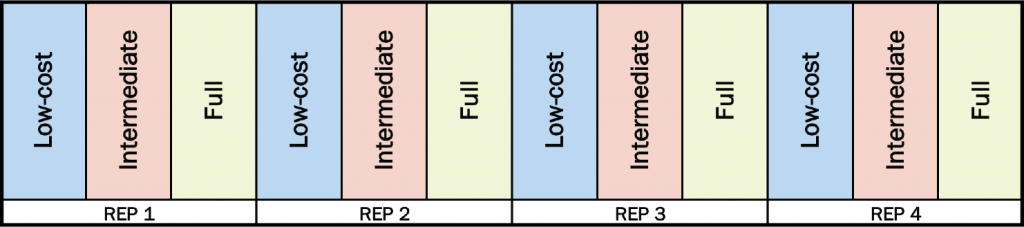

Bennett implemented four replications of each of the three treatment packages in strips that measured 30 ft wide and ran the length of the field (Figure A1).

Measurements

On May 11, Bennett clipped samples of aboveground cereal rye cover crop growth (stems and leaves) from each of the 12 strips. We determined the amount of cover crop biomass by weighing the samples after air-drying for four weeks.

Bennett assessed weed pressure in each strip on Sept. 24 by selecting seven random points along a 100-pace transect and counting the number of weeds in a 6-ft diameter (28 ft2 area).

On Oct. 9, Bennett harvested the soybeans and recorded yields from each individual strip.

Data analysis

To rank the effects of the herbicide packages Bennett compared, we calculated Tukey’s least significant difference (LSD) for each measurement: weed count and soybean yield. For each measurement, we assigned different rankings to the packages if the difference resulting from any two packages was greater than or equal to the LSD – we also refer to this as a statistically significant effect. On the other hand, if the difference resulting from any two packages was less than the LSD, we consider the packages to be statistically similar (those two packages received the same ranking). We used a 95% confidence level to calculate the LSDs, which means that we would expect our rankings to occur 95 times out of 100. We could make these statistical calculations because Bennett’s experimental design involved replication of the three herbicide packages (Figure A1).

Results and Discussion

Cover crop biomass

On average, Bennett’s field contained 2,993 lb/ac of aboveground cover crop biomass prior to termination of the cover crop and prior to Bennett implementing the three herbicide packages. Cover crop biomass (residue) is important for weed control because soil surface cover by the residue physically suppresses weeds.[3]

Sam Bennett seeded soybeans into nearly 3,000 lb/ac of cereal rye cover crop biomass. Photo taken June 6, 2019.

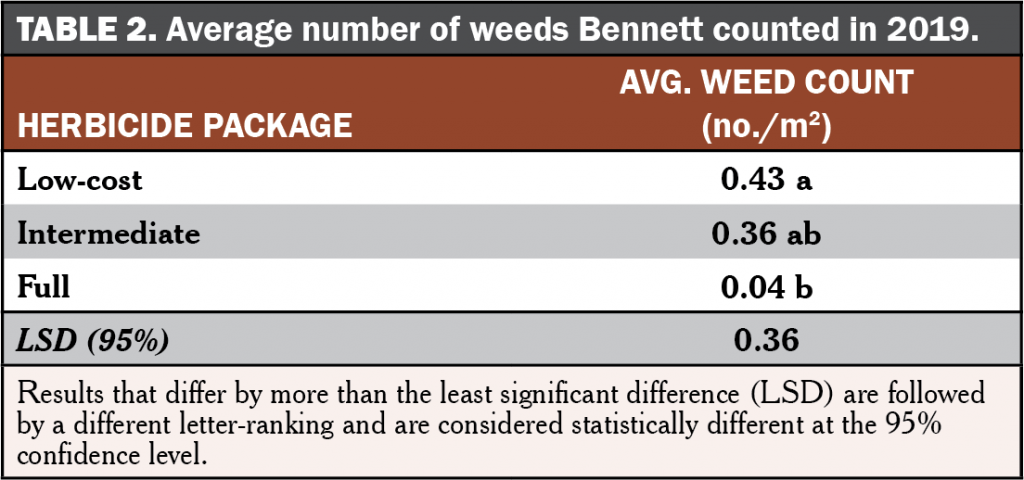

Weed counts

Giant ragweed, waterhemp, marestail and volunteer corn were the predominant weed species Bennett observed. Bennett counted the least number of weeds in strips receiving the full herbicide package (Table 2). Though, weed pressure in the field could be considered rather low – average weed counts for each package were less than one weed per square meter.

Soybean yields

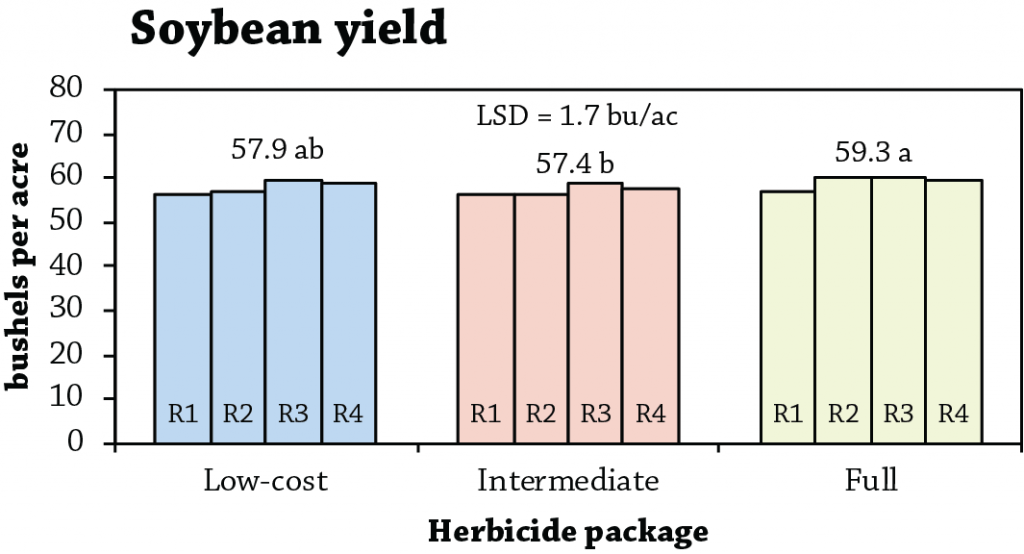

Soybean yields were statistically equivalent between the full and low-cost herbicide packages; the intermediate package resulted in the lowest yield (Figure 1). Across treatments, soybean yields at Bennett’s fell just below the five-year Ida County average of 62 bu/ac.[4]

Figure 1. Soybean yields at Sam Bennett’s in 2019. Columns represent individual strip yields. Above each set of columns is the treatment mean. Results that differ by the least significant difference (LSD; 1.7 bu/ac) are followed by a different letter-ranking and are considered statistically different at the 95% confidence level. Click to enlarge.

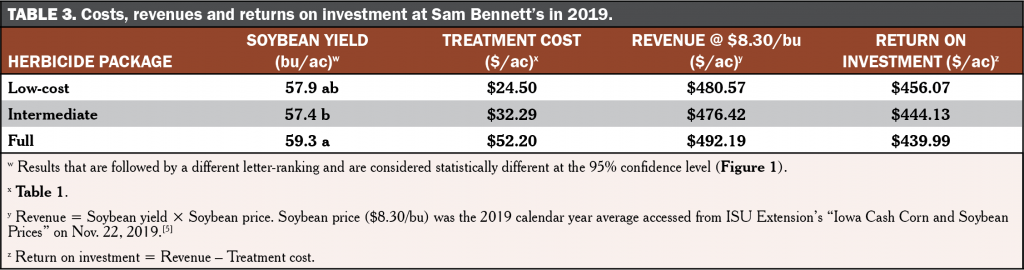

Economic considerations

Among all three herbicide packages tested, Bennett scored top returns on investment with the low-cost package (Table 3). Though yields between the low-cost and full herbicide packages were statistically similar, returns on investment for the low-cost package were greater by $16.08/ac, owing to reduced costs (less herbicide used).

Conclusions and Next Steps

Bennett’s results provide further evidence that a cereal rye cover crop can suppress weeds and reduce herbicide inputs in soybeans. In a similar trial he conducted last year, Bennett found that of the three herbicide packages he compared in soybeans that followed a cereal rye cover crop, the herbicide package that did not feature any residual activity resulted in his best return on investment.[1] That package included pre-plant, pre-emerge/burndown and post-emergence applications of Salvo, Roundup Powermax and Clethodim. At the conclusion of that trial, Bennett wondered if he could further reduce herbicide use. In the present trial, Bennett’s low-cost package only included pre-emerge/burndown and post-emergence applications of glyphosate (again, no residual activity). With this package, he saw similar soybean yields to the full package (included residual activity, most expensive package) with nearly $28/ac less in costs. These findings also align with those recently published in a meta-analysis of 46 studies from around the world which concluded “cover crops could provide early weed control comparable to those provided by chemical and mechanical weed control methods in cropping systems.”[3]

“This trial worked toward quantifying the benefit of cereal rye in suppressing weeds in the early part of the growing season.” Bennett said. “I’m building confidence that I can rely on the cover crop more heavily, and build a lower cost and reduced chemistry herbicide program around the cover crop.”

With proper management, it seems that farmers could reallocate some expenses typically spent on herbicides to cover crop seed and planting. In addition to weed suppression, farmers would reap other proven environmental benefits of cover crops such as reduced soil erosion, reduced nutrient loss and improved water infiltration.

Appendix – Trial Design and Weather Conditions

Figure A1. Sam Bennett’s experimental design. He implemented four replications of each of the three herbicide packages (12 strips total). This design allowed for statistical analysis of the results. Click to enlarge.

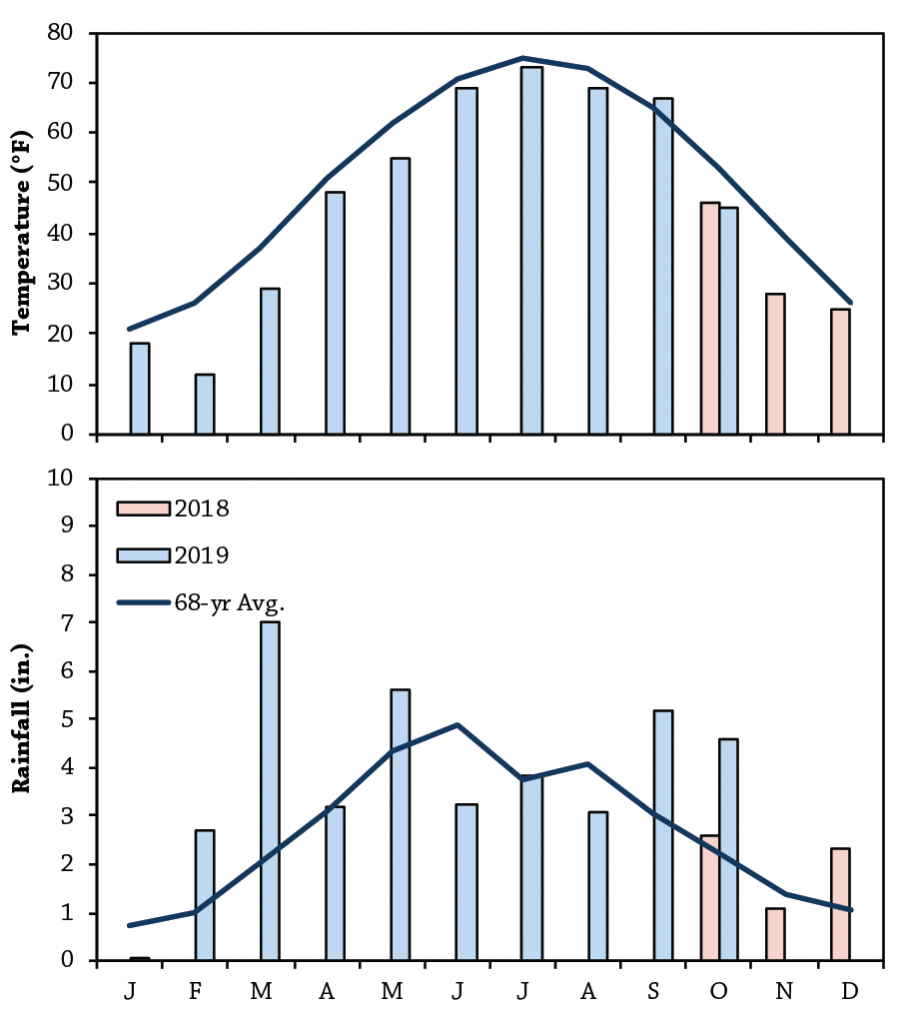

Figure A2. Mean monthly temperature and rainfall for Oct. 1, 2018 through Oct. 31, 2019 and the long-term averages at Holstein, the nearest weather station to Bennett’s farm in Galva (about 8 miles away).[6] Click to enlarge

References

- Nelson, H. and S. Bennett. 2018. Cereal Rye Cover Crop for Reducing Herbicides in Soybeans. Practical Farmers of Iowa Cooperators’ Program. https://practicalfarmers.org/research/cereal-rye-cover-crop-for-reducing-herbicides-in-soybeans/ (accessed November 2019).

- Plastina, A., A. Johanns and G. Wynne. 2019. 2019 Iowa Farm Custom Rate Survey. Ag Decision Maker. Iowa State University Extension and Outreach. https://store.extension.iastate.edu/product/2019-Iowa-Farm-Custom-Rate-Survey (accessed November 2019).

- Osipitan, O.A., J.A. Dille, Y. Assefa and S.Z. Knezevic. 2018. Cover crop for early season weed suppression in crops: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Agronomy Journal. 110:2211–2221. https://dl.sciencesocieties.org/publications/aj/abstracts/110/6/2211 (accessed November 2019).

- US Department of Agriculture-National Agricultural Statistics Service. Quick stats. USDA-National Agricultural Statistics Service. https://quickstats.nass.usda.gov/ (accessed November 2019).

- Johanns, A. 2019. Iowa Cash Corn and Soybean Prices. Ag Decision Maker File A2-11. Iowa State University Extension and Outreach. https://www.extension.iastate.edu/agdm/crops/pdf/a2-11.pdf (accessed March 2019).

- Iowa Environmental Mesonet. 2019. Climodat Reports. Iowa State University. http://mesonet.agron.iastate.edu/climodat/ (accessed November 2019).