This research was funded by the Iowa Department of Agriculture and Land Stewardship, Division of Soil Conservation and Water Quality.

In a Nutshell:

- Landon Brown, Will Cannon, Jeremy Gustafson, Aaron Lehman and Sam Ose were recruited by Practical Farmers of Iowa to participate in an on-farm research project that was part of a multi-state effort coordinated by researchers at North Carolina State University and USDA in Beltsville, MD.

- Each farmer tested the effect of cereal rye cover crops on either corn or soybeans yields as well as soil moisture with sensors provided by NCSU and installed by PFI staff.

Key Findings:

- Soybean yields were improved by the cover crop at Cannon’s but corn yields at Ose’s were reduced by the cover crop. Brown, Lehman and Gustafson observed no effect of cover crop on cash crop yield.

- Soil moisture sensors provided reliable data at three of the five farms. Cannon saw no effect on soil moisture from the cover crop; Brown saw some improvement of soil moisture from the cover crop; and Gustafson saw reduced soil moisture from the cover crop.

Background

Prior research in Iowa and Indiana has shown cereal rye cover crops to increase water infiltration1 and soil moisture retention2,3 in corn-soybean systems. Recently, Practical Farmers of Iowa was invited to join a multi-state effort to further investigate the effects of cover crops on soil water availability. These on-farm research trials will contribute to a national on-farm trial network coordinated by the Southern Cover Crops Council at North Carolina State University and is part of the ongoing, USDA-funded initiative known as Precision Sustainable Agriculture.4 Results of the national on-farm trials are building a decision support tool (DST) aimed at increasing knowledge about cover crop use for improving water and nutrient management and increasing the economic and environmental performance of agricultural lands. In fall 2021, five PFI farmers, initiated on-farm research trials of replicated paired strips of cover crop vs. no cover crop to investigate the effect on crop yields and soil water availability for the 2022 growing season. At the onset of the project, one of the participating farmers, Will Cannon, said, “[This research] will validate that our current cover crop practices are working or if we need to make changes.”

Methods

Design

To determine the effect of cover crops on crop yields and soil moisture, each cooperator compared two treatments:

- Cover – overwintering cover crop seeded in fall 2021.

- No-cover – no cover crop seeded.

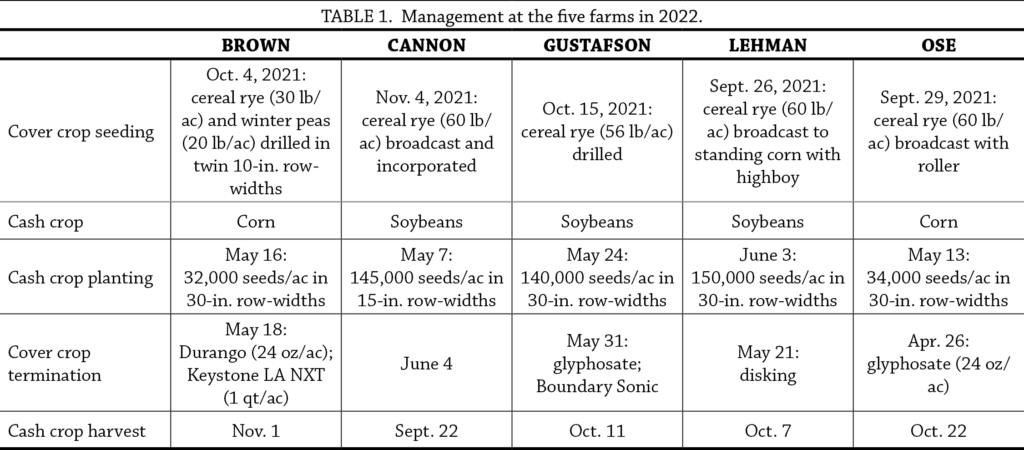

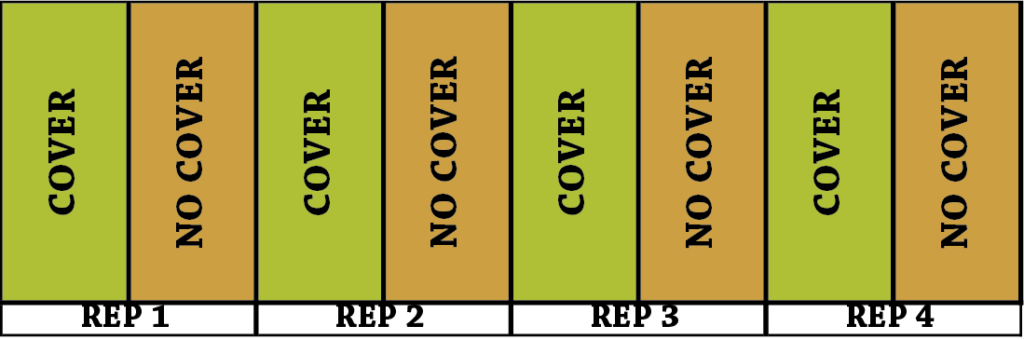

Field management for each farm is presented in Table 1. All farms assigned treatments to alternating strips and replicated each treatment four times (Figure A1). By farm, all strips were managed similarly apart from the cover crop treatments.

Measurements

Former PFI research coordinator, Hayley Nelson, installing soil moisture sensors at Sam Ose’s farm on June 16, 2022.

Cover crop biomass samples were collected at each farm just prior to termination. Samples air dried for at least 4 weeks before weighing to estimate aboveground biomass. Soil moisture sensors, provided by North Carolina State University, were installed in June by PFI staff after crop emergence at each farm. Sensors routinely collected soil moisture (volumetric water content) from four depths: surface, 6 in., 18 in. and 30 in. Each cooperator harvested corn or soybeans from each strip and recorded yields and percent moisture. Corn yields were adjusted to 15.5% moisture; soybean yields were adjusted to 13% moisture.

Data analysis

To evaluate effects of the cover crop treatments on crop yields we calculated treatment averages for each measurement then used a t-test to compute the least significant difference (LSDs) at the 95% confidence level. The difference between each treatment’s average soybean yield is compared with the LSD. A difference greater than or equal to the LSD indicates the presence of a statistically significant treatment effect, meaning one treatment outperformed the other and the farmer can expect the same results to occur 95 out of 100 times under the same conditions. A difference smaller than the LSD indicates the difference is not statistically significant and the treatment had no effect. We could make these statistical calculations because each cooperators’ experimental design involved replication of the treatments (Figure A1).

Results and Discussion

Cover crop biomass

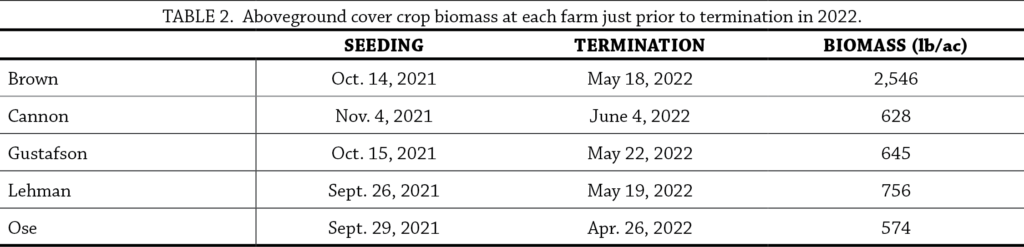

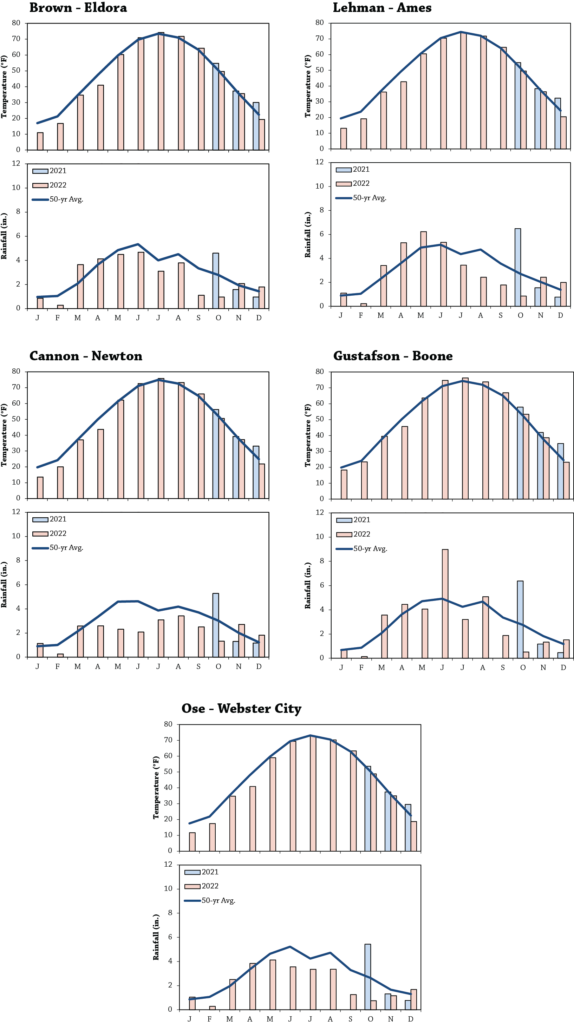

The amount of cover crop growth achieved across all farms was relatively low (Table 2). The exception was Brown’s where just over 2,500 lb/ac of aboveground biomass was observed just prior to termination. Varying cover crop performance is likely a reflection of the varied precipitation and temperature patterns fall 2021–spring 2022 across sites (Figure A2).

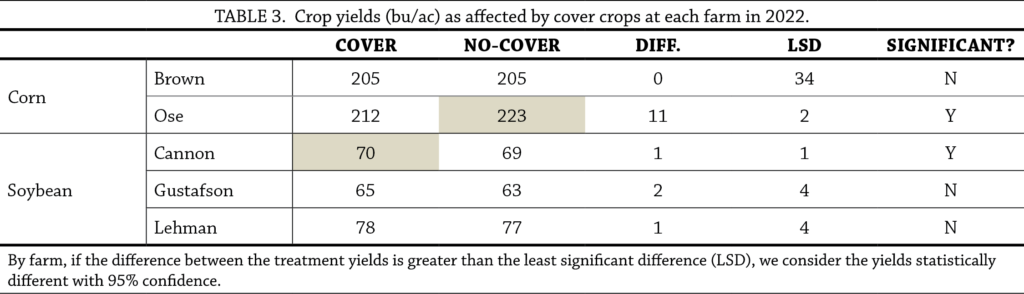

Crop yields

Cash crop yields were unaffected by cover crops at three of the five farms (Brown, Gustafson, Lehman) (Table 3). At Ose’s farm, corn yields were reduced by 11 bu/ac by the cover crop and at Cannon’s, soybean yields were statistically improved by the cover crop by 1 bu/ac. Interestingly, cover crop biomass was least at Ose’s and Cannon’s among the five farms (Table 2), yet crop yields were only affected at these two farms.

Soil moisture

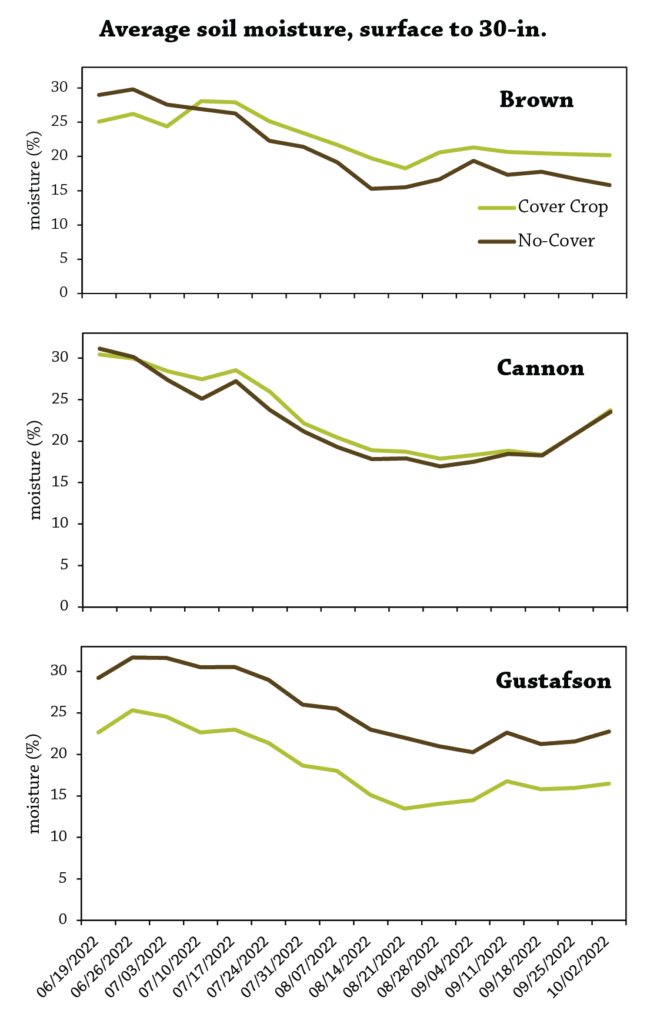

Soil moisture sensors registered usable data at Brown’s, Cannon’s and Gustafson’s only (sensors unfortunately failed at Lehman’s and Ose’s). Figure 1 shows the varying effect of the cover crop on soil moisture at the three farms. At Brown’s, the cover crop resulted in drier soil conditions in June, but the reverse was true beginning in mid-July, and this continued through the rest of the growing season. At Cannon’s, it was safe to say that soil moisture between the cover crop and no-cover treatments did not tend to differ during the growing season. At Gustafson’s, soil moisture was consistently drier in the cover crop treatment from start to finish.

Figure 1. Soil moisture through the growing season averaged across the surface, 6-in., 18-in. and 30-in. depths at Landon Brown’s, Will Cannon’s and Jeremy Gustafson’s in 2022.

Conclusions and Next Steps

Where the cover crop appeared to have no impact on soil moisture during the summer (Cannon’s), we also observed a slight improvement in crop yield compared to the no-cover treatment (Table 3). Interestingly, Brown observed no effect of the cover crop on corn yield, but the cover crop did seem to improve soil moisture during the summer. This effect on soil moisture was perhaps due to Brown reaping the most cover crop biomass of all the sites (Table 2) – the mulch from the leftover cover crop residue might have helped preserve soil moisture. At Gustafson’s, Lehman’s and Ose’s, there was no effect of cover crop on cash crop yield, though, Gustafson saw the cover crop reduce soil moisture (Figure 1). Results from the five trials in Iowa in 2022 point to the importance of trialing cover crops over multiple years and on multiple farms.

Appendix – Trial Design and Weather Conditions

Figure A1. The cooperators’ experimental design consisted of four replications of the two treatments. This design allowed for statistical analysis of the data.

Figure A2. Mean monthly temperature and rainfall during the trial period and the long-term averages the nearest weather station to each farm.5

Click to enlarge

References

- Qi, Z.; Helmers, M. J.; Kaleita, A. L. Soil Water Dynamics under Various Agricultural Land Covers on a Subsurface Drained Field in North-Central Iowa, USA. Agric. Water Manag. 2011, 98 (4), 665–674. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agwat.2010.11.004.

- Basche, A. D.; Kaspar, T. C.; Archontoulis, S. V.; Jaynes, D. B.; Sauer, T. J.; Parkin, T. B.; Miguez, F. E. Soil Water Improvements with the Long-Term Use of a Winter Rye Cover Crop. Agric. Water Manag. 2016, 172, 40–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agwat.2016.04.006.

- Daigh, A. L.; Helmers, M. J.; Kladivko, E.; Zhou, X.; Goeken, R.; Cavdini, J.; Barker, D.; Sawyer, J. Soil Water during the Drought of 2012 as Affected by Rye Cover Crops in Fields in Iowa and Indiana. J. Soil Water Conserv. 2014, 69 (6), 564–573. https://doi.org/10.2489/jswc.69.6.564.

- Precision Sustainable Agriculture. Precision Sustainable Agriculture. https://www.precisionsustainableag.org (accessed 2023-06-12).

- Iowa Environmental Mesonet. Climodat Reports. http://mesonet.agron.iastate.edu/climodat/ (accessed 2023-06-12).