The Proof is in the Soil

PFI farmers are testing if they can lower nitrogen rates without hurting yield on fields with long-term soil health practices.

Improving soil health has been a top priority for PFI farmers since our inception. While the terms people use to refer to soil health have changed over the years, PFI members have been leading the way since the 1980s in adopting soil health-promoting practices like ridge-till, diverse crop rotations, adding grazing livestock and planting cover crops to keep living roots in the ground.

Some of the earliest on-farm research projects in PFI’s Cooperators’ Program focused on these topics, as well as how to apply less manure and fertilizer. Now, Practical Farmers members are leading the way once more by participating in a next-generation on-farm soil health experiment.

Practical Farmers of Iowa is heading an on-farm research project involving 20 farms across Iowa looking at whether farmers who have been investing long-term in soil health-promoting practices can reduce the amount of nitrogen fertilizer they apply to corn without sacrificing yield.

The project idea is based on an emerging body of research showing, in essence, that as soil health holistically improves, the soil ecosystem is better able to sustain itself. Experiments by scientists from the Midwest and southeast U.S. have found that as soil health metrics like organic matter, active carbon or microbial activity improve, crops need less nitrogen fertilizer to thrive. A healthy soil is rich in nutrients; adding nitrogen fertilizer just doesn’t do much good.

“The results of these trials drastically improved our farms, and overall, they played an important role in building and maintaining PFI’s farmer-to-farmer network.”

– Vic Madsen

The results are adding heft to the Natural Resources Conservation Service’s dynamic definition of soil health as “the continued capacity of soil to function as a vital living ecosystem that sustains plants, animals and humans.” For farmers, the results mean that as they improve their soil’s health, they may be able to reduce the amount of fertilizer they need to get the same yields – a win for the environment and their net returns.

History of Trialing Nitrogen

The current project got underway in fall 2021 – but it isn’t the first time PFI members have tackled the question of fertilizer use on the farm. The farm crisis of the 1980s that helped usher PFI into existence forced many farmers, and early PFI members, to take a hard look at their farming practices. While some farmers survived the crisis by farming more land (“getting big”), many more could not afford to purchase or rent more acres, and were forced to “get out.”

But several of PFI’s early members took a middle approach: They thought that by cutting the most expensive input costs – such as nitrogen fertilizer – they could improve profit margins enough to get by. From 1988-1993, farmers participating in PFI’s newly established Cooperators’ Program conducted 57 trials that compared their typical high fertilizer rate with a reduced rate of their choosing. Across sites, the average difference between high and low rates was 56 units of nitrogen per acre.

In 88% of those trials (50 of the 57), the farmers involved found that applying the high rate offered no statistical advantage to corn yield – and that in most cases, they were applying more nitrogen than they needed. “We felt like we were ‘on a mission from God,’ to quote the iconic line from the popular 1980 movie, ‘The Blues Brothers,’” says Vic Madsen, who farms near Audubon, Iowa, and participated in those early fertilizer trials.

“We learned that we could save money and improve our bottom lines by reducing application rates, and feel better about being stewards of the environment in doing so,” he says. “The results of these trials drastically improved our farms, and overall, they played an important role in building and maintaining PFI’s farmer-to-farmer network.”

Since those first trials in the late 1980s, more than 250 farmers have conducted nearly 1,500 research trials on their farms. Today, the Cooperators’ Program brings together a community of curious and creative farmers from across the agricultural spectrum who take a scientific approach to improving their farms.

The Next Generation

Alec and Rachel Amundson, who farm with Rachel’s family, the Norbys, near Osage, Iowa, weren’t even born yet when the first PFI nitrogen trials got started in the late 1980s. But farming practices that focus on soil health and water quality have long been important on their family farm and in their area.

“My dad and uncles, who we now are transitioning the farm from, were some of the first ones to start things like no-tilling and strip-tilling,” Rachel says. “With other farmers in the neighborhood, they started doing cover crops and saw the benefits.” Soon after the Iowa Nutrient Reduction Strategy was released in 2013, a group in the Rock Creek Watershed, where the Amundsons farm, was the first in the state to create a watershed plan specifically tailored to addressing the goals laid out in the new strategy.

As in the 1980s, keeping the farm going is the main reason the Amundsons focus on soil health. But environmental stewardship is another key motivating factor, just as it was for the previous generation of PFI members. “As the next generation coming on, we want to continue that,” Rachel says. “Hopefully our farm can last for many generations. We like to kayak on Rock Creek. We like to boat on the Cedar River, and to us, to have those quality bodies of water around us, we know we’re making a difference with cover crops.”

Now, Rachel is a partner in Sponheim Sales and Services, a local business that strives to help farmers adopt conservation practices like cover crops, strip-till and no-till. Since becoming involved in the business, the Amundsons have begun to grow more small grains, like oats and rye, for cover crop seed, opening the door to growing a “super cover crop” – red clover.

Red clover is often planted either at the same time as oats or interseeded into a young stand of rye. After the small-grain crop is harvested in the middle of the summer, the clover takes off, capturing the full power of the summer sun – and more importantly, fixing nitrogen that can be used by the subsequent corn crop.

“We’re trying to learn how much nitrogen we actually get out of a clover crop like this in our system,” Alec says. “For us, nitrogen is one of the largest expenses in growing corn, behind land and seed costs. Something like [red clover] that’s actually putting nitrogen into the soil, it’s fixing nitrogen cheaper than we can buy it. The clover is just pulling it out of the atmosphere and making it available for us.”

As prices for nitrogen fertilizer started climbing over the past couple of years, and echoing questions that animated PFI farmers in the 1980s, Rachel and Alec started wondering: Could we reduce our nitrogen rate and save money? Enter PFI nitrogen trials 2.0.

Nitrogen Trials 2.0

For this newest PFI-led fertilizer project, PFI staff recruited farmers, including the Amundsons, who have been using soil health-promoting practices for at least five years. Using a replicated strip-trial design, farmers are comparing their usual fertilizer rate with a rate that is reduced by 50 pounds of applied nitrogen per acre. If they can maintain corn yields at the reduced rate, results might spark confidence to reduce (or at least question) fertilizer rates going forward, much like what happened for the original cohort of farmers who trialed fertilizer rates.

To some degree, this project is asking: Is the ability to reduce nitrogen fertilizer without losing corn yield a simple yet robust test of soil health? The project’s premise echoes the sentiment of the idiom “the proof of the pudding is in the eating” – in a sense, it suggests that how well the crop performs with less fertilizer is a reflection of the soil’s health.

And what if the reduced rate ends up lowering corn yields and financial returns? The farmers will still have gained valuable information: They can probably be satisfied that their typical rate is the right rate for their farm. Knowing this could encourage them to adopt more soil health-promoting practices in the hope they could eventually reduce that fertilizer rate (and expense).

“Something like [red clover] that’s actually putting nitrogen into the soil, it’s fixing nitrogen cheaper than we can buy it. The clover is just pulling it out of the atmosphere and making it available for us.” – Alec Amundson

Cost Savings and Environmental Benefits

Scientists have long shown that soil health-promoting practices pay off in the long run by reducing soil erosion and improving soil-water infiltration. And while the original nitrogen trial participants of the 1980s saw that improvements in water quality accompanied cost-savings, this new generation believes there’s a benefit to the climate. Cutting back on rates of manufactured nitrogen significantly lessens the greenhouse gas emissions associated with their farms.

As Alec says, legumes “fix” or capture nitrogen from the atmosphere, converting the element into a form plants can use. Commercially produced nitrogen fertilizer mimics that process synthetically – but with a high energy toll. The Haber-Bosch process – the industrial process invented over 100 years ago to artificially fix nitrogen – accounts for 2% of global carbon dioxide emissions. As we look to improve the resilience of our farming systems, green manure crops – like red clover – will play a big role in a truly climate-smart agriculture.

But the short-term benefits of planting clover, and other soil health-promoting practices, may not be visible right away. If research could show short-term advantages, like saving money on nitrogen fertilizer, more farmers might be swayed to adopt soil health practices.

Year One Results

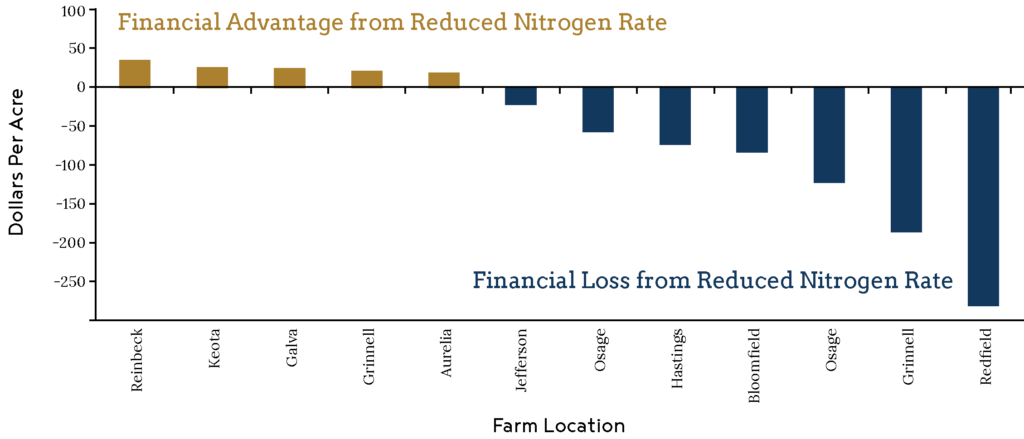

By mid-November 2022, results from 12 trials showed that in half of them, farmers found a $25 per acre financial advantage, on average, from reducing their fertilizer rate. Other participants saw declines in both corn yield and financial returns from reducing their fertilizer rate.

Corn pays when the amount of grain produced brings a financial return greater than the costs spent to produce the corn. As of mid-November, five sites reported a financial advantage from reducing fertilizer rate to corn: Reducing their fertilizer rate reduced their production costs but didn’t harm their corn yields. Seven other sites reported financial losses from reducing their fertilizer rate: Though they reduced their fertilizer expense, corn yields and financial returns were also reduced.

Jon Bakehouse and Alec and Rachel Amundson took these results as a sign that reducing their fertilizer rate by 50 pounds per acre might have been too large of a cut from their typical rates. “Normally, we wouldn’t have even tried reducing [nitrogen] by 50 pounds,” Jon says. The research trial setting, however, made it possible for him to take risks he wouldn’t otherwise have felt comfortable with by testing that aggressive fertilizer cut in just a small area.

For Alec, the project has provided important data to back up his and Rachel’s thoughts on nitrogen application. “It was a great way to verify our thinking of how to cut fertilizer when planting corn after clover,” he says. “We learned where and how we might save money on nitrogen.”

Based on their respective results, both Jon and the Amundsons think that reducing their fertilizer rates by 20 or 30 pounds per acre would have been the sweet spot. The mixed results aren’t that surprising because all the farms involved are approaching the trial from their own unique standpoints: different typical rates, different crop rotations, different local climates and existing soil properties. In other words, everyone involved sits at a different point in their soil health journey. Some have found that they can afford to cut fertilizer rates; others have learned that they’re already applying a suitable rate or have room to improve their soil’s health – or both.

“I knew we could grow good corn with less nitrogen,” says Sam Bennett, one of the farmers to see a cost benefit from cutting nitrogen. “But knowing what happens when corn runs out of nitrogen, I habitually over-apply fertilizer. This trial helped give me the confidence to take a deeper look at what rates I’m planning to apply.”

Notes from the Field

The new nitrogen project lets PFI farmers choose the fields they used soil health practices on to enroll in the study. By doing this – and letting them choose their typical and reduced nitrogen rates – the project empowers them as the scientist and, ultimately, makes the data meaningful and relevant to each of them.

Here are a few of the PFI farmers putting their farms’ soil health to the test:

Here are a few of the PFI farmers putting their farms’ soil health to the test:

Sam Bennett

Sam Bennett

Galva, Iowa

Farm overview: Corn-soybean rotation with cereal rye cover crops and either no- or strip-tillage

Typical N rate: 189 pounds per acre

Reduced N rate: 139 pounds per acre

“I hope to see if improved soil health practices can reduce the need for inputs.”

Chris Deal

Jefferson, Iowa

Farm overview: Corn-soybean rotation with cereal rye and winter wheat cover crops and limited tillage

Typical N rate: 200 pounds per acre

Reduced N rate: 150 pounds per acre

“I have made a conscious effort to utilize sustainable farming practices, including no-till and cover crops and I hope to right-size the amount of nitrogen I’m using on my farm. By focusing on the amount of N that offers peak profitability, rather than peak yield, I hope to avoid the use of unnecessary fertilizer and further reduce the possibility of leaching and runoff from my farming operation.”

Alec & Rachel Amundson

Alec & Rachel Amundson

Osage, Iowa

Farm overview: Diversified crop rotation including corn, soybeans, oats, cereal rye and red clover cover crops and no- or strip-till

Typical N rate: 130 pounds per acre

Reduced N rate: 80 pounds per acre

“[This trial will impact our farm by] helping to fine-tune our nitrogen management.”

Jon Bakehouse

Jon Bakehouse

Hastings, Iowa

Farm overview: Corn-soybean rotation with cereal rye cover crops seeded after each corn harvest and no tillage. Cattle graze crop residue and cover crop forage from September to April.

Typical N rate: 151 pounds per acre

Reduced N rate: 95 pounds per acre

“[This trial will] give me the confidence to either reduce nitrogen rates or be secure in the knowledge we aren’t over-applying nutrients. [I also hope to discover] unexpected outcomes that kick-start thinking in new and different directions.”

Bill Frederick

Bill Frederick

Jefferson, Iowa

Farm overview: Corn-soybean rotation with winter wheat, turnip cover crops and no tillage. After harvest, cattle graze the crop residue and cover crop forage from October to May.

Typical N rate: 150 pounds per acre

Reduced N rate: 100 pounds per acre

“If it works, it will greatly reduce nitrogen costs and increase profitability.”

Nathan Anderson

Nathan Anderson

Aurelia, Iowa

Farm overview: Corn-soybean rotation with cereal rye cover crops, no tillage and composted cattle or turkey manure. Cattle graze crop residue and cover crop forage each winter.

Typical N rate: 158 pounds per acre

Reduced N rate: 105 pounds per acre

“I hope my research site, combined with other farmer-cooperator sites and our collective results, can reform the narrative around nitrogen fertilization and use for the benefit of farmers and the environment.”

Want to Get Involved? Sign up Today!

Do you want to test nitrogen use on your farm?

We’re looking for corn farmers in Illinois, Iowa, Minnesota, Missouri and Nebraska. Eligible fields will have at least a five-year history of soil health practices (cover crops, diverse rotations, integrated grazing, reduced tillage, etc.).

What’s Involved?

The trial involves eight treatment strips that are about 2 acres each. Four strips (~8 acres) will receive your typical fertilizer rate, and four strips (~8 acres) will receive the reduced rate. Total trial footprint: ~16 acres

Why Participate?

- You’ll receive a stipend for completing the trial.

- You’ll learn more about fertilizer use in corn on your farm.

- You will contribute vital data to a broader effort by PFI and partners to gauge risk associated with reducing N fertilizer.

Reach out to PFI’s senior research manager, Stefan Gailans, to sign up or learn more at stefan.gailans@practicalfarmers.org

“Still don’t see any streaking.” Kevin Veenstra took weekly photos of his experiment near Grinnell, Iowa, through the growing season. By mid-August 2022, the corn that received 108 pounds of nitrogen fertilizer looked just as healthy and robust as the corn that received 158 pounds. But in the end, the higher fertilizer rate scored better yields and financial returns. Trial results often serve as a check, either confirming or refuting the eye test. “Without the trial I may have cut back nitrogen too much too soon,” Kevin says.