Considerations for choosing the right oat variety

Matt Miller of Bristow, Iowa knows the importance of variety selection in oats. Matt farms 1,000 acres of conventional and organic ground and oats have been a steadfast part of his 4-year rotation in all of his transition and organic fields. Though Matt typically seeds two varieties, to lessen risk and ensure his oat crop is successful each year, he seeded three varieties in 2021. On our November shared learning call we heard from Matt about the factors that influence his variety selection.

Matt Miller of Bristow, Iowa knows the importance of variety selection in oats. Matt farms 1,000 acres of conventional and organic ground and oats have been a steadfast part of his 4-year rotation in all of his transition and organic fields. Though Matt typically seeds two varieties, to lessen risk and ensure his oat crop is successful each year, he seeded three varieties in 2021. On our November shared learning call we heard from Matt about the factors that influence his variety selection.

When beginning to think about his oats and choosing varieties, Matt starts with his end goal – the market. “With corn and soybeans you can sell them in any town in Iowa but that’s not true with oats. We really have to think about who our end user is.”

Whether he sells food-grade oats to Grain Millers or feed-grade oats to a closer elevator, Matt notes “they all want to have good test weight, so that’s my number one selection requirement. I want an oat that is at the top end of test weight,” adding “I don’t want to grow something and have a difficult time selling it.”

Test weight is often a make or break deal for growers. Oats that are too light, with a test weight below 36 pounds per bushel, are much harder to market and go for a lower price than heavier oats with a test weight of at least 38 pounds per bushel or above. While many remark that heat is the enemy of high test weight, infestations of crown rust can reduce test weight just as much, if not more, than weather conditions.

Breaking down variety disease resistance

Crown rust is the most damaging and common pathogen for oats. “It seems like every year there’s some degree of disease,” Matt notes. Crown rust infects the leaves of oats and reduces photosynthesis, lowering grain fill and resulting in thin kernels. Warm and wet years are especially problematic. “When we have more moisture, that increases the potential for diseases” says Matt, “so I choose varieties that are more naturally tolerant of crown rust.” For organic farmers like Matt, who cannot rely on a fungicide application, choosing a variety that has built in resistance is of the utmost importance.

While modern breeding efforts strive to select for crown rust resistance, the disease is constantly evolving, making sustained resistance challenging. In general, older oat varieties are more susceptible to crown rust, since their resistance has been overcome by the evolution of the disease. In contrast, newer varieties are more likely to be resistant to crown rust, given that the disease hasn’t had as much time to mutate and evolve.

Data from South Dakota State University, 2020.

*Scored on a scale of 1-9. 1 = no symptoms, 9 = very severe symptoms

The best way to know how varieties are faring in relation to crown rust pressure is to look at University trials. South Dakota State University assigns annual disease ratings for crown rust and posts them in their trial reports. The table to the right shows disease scores from 2020 and is sorted by the year a variety was released, from oldest to newest. All varieties showed some level of disease in 2020, however the varieties released before 2016 scored worse than the newer varieties. The exception is Deon, which was released in 2013 and continues to have good disease resistance. Given that variety age isn’t always a good predictor, it’s important to look at the data to see which varieties continue to have strong resistance over time.

Finding information most relevant to your farm

University trials

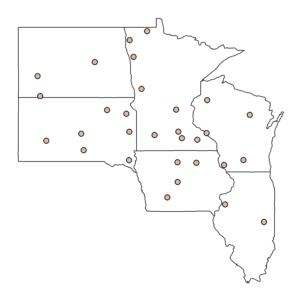

University oat variety trial locations across the Midwest in 2020 and 2021 – note that trial locations may vary from year to year.

University trials are the best source of information when predicting oat variety performance. Universities in Illinois, Iowa, Minnesota, North Dakota, South Dakota, and Wisconsin test oat varieties annually and publish their results . Oats, like all crops, have genotype-by-environment interactions, meaning that a variety that performs best in one location may not perform well in another location. Therefore, farmers should look most carefully at variety trial locations that are closest to them to get the best predictions for their own farm.

Given that every year is different, most states publish two- or three-year averages for each oat to help give growers an idea of how varieties perform over time. Similarly, it can be useful to peek at other variety trial locations to get a sense of what varieties are consistent across different soil types and weather patterns. In Iowa, for instance, some of the varieties that consistently meet test weight thresholds of 38 pounds per bushel are Antigo and Sumo.

Predictive tools

Looking at the map above, it’s easy spot areas where there are no trials, like Southeast Iowa. To address these gaps in variety trial locations while still giving growers accurate recommendations, Practical Farmers has released a variety trial selector tool in conjunction with University small grain breeders. The tool leverages existing variety trial data and runs it through genotype-by-environment models to predict which oats varieties are likely to perform best given a grower’s ZIP code and their end market. The tool predicts for yield, test weight, and crown rust resistance.

To test the accuracy of the tool’s predictions, PFI has conducted on-farm trials across Iowa in 2020 and 2021 where growers plant their traditional variety alongside one selected by the model. In both years, the results were mixed. Most sites didn’t see a different in performance, meaning there’s room yet to improve the model’s predictions.

Decision time

One of Matt Miller’s biggest pieces of advice for choosing a variety? Grow more than one. “I always like to keep another oat because everyone year is different, and I like to make sure that I’m always happy with my main oat.” Matt’s been using Reins for years and continues to be pleased with its performance, but he will still plant a second oat variety each year. The last few years he’s been using Shelby427 alongside Reins.

As for how and when he makes his decisions he says, “I review varieties during the winter months and check how my current variety compares to the new ones that are listed. If there’s a new one that looks promising, I’ll buy enough seed to plant 20 acres and see how it compares. And I’ll give it another chance next year.” Matt likes to give each variety at least three years before he cycles it back out, “unless it really flops” he notes. Since every year comes with its own set of unpredictable challenges, trialing varieties for multiple years allows Matt to see how performance varies across dry or wet conditions.

Interested in learning more about small grains? Join future shared learning calls and get resources on small grain production delivered straight to your inbox by signing up for our monthly small grains newsletter to get details sent directly to your inbox.”