Cover Crop and Reduced Tillage Benefits in the Field and Beyond

“Is it ever going to stop raining?” Farmers across Iowa are wondering this year. With the wet and cold weather it’s been hard to get into the field to plant. At the same time producers are feeling the strain of low crop prices and weighing their options for how to proceed for the year ahead. Under the circumstances, reducing tillage via strip till or no-till practices deserves another look as a way to improve soil health to promote water infiltration and prevent erosion at the field level, and also keep input costs low and support farmer health and well-being. Switching from a conventional tillage system to a no-till or strip-till system is an excellent place to begin improving productivity and resiliency both in the field and beyond.

Manage for Soil Structure…

Soil structure is critical to developing resilient fields that can be planted into even after a significant rainfall. Tillage, counterintuitively, breaks up pockets of air in the soil and packs soil particles in more tightly – especially if the land lacks crop and root residue. This results in the depletion of organic matter and reduction of water holding capacity in the soil (Iowa State University, 2004). Reduced tillage allows fields to take on more rain than tilled fields, decreasing the likelihood of having to delay planting or harvesting due to wet soil.

In a research report, Jodi Dejong-Hughes and Aaron Daigh, soil scientists from the University of Minnesota and North Dakota State University, describe this idea concisely: “Soils with good soil structure (soils with several years of reduced or no tillage) are much more efficient at draining this excess moisture from the seedbed and allowing air to enter through the largest pores.” More porous soils can absorb water more efficiently.

Dean Sponheim of Sponheim Ag Services shows attendees of a 2018 PFI field day cereal rye and rapeseed seedlings in standing corn. The cover crops were flown on a week prior.

Additionally, reduced tillage continues to protect the soil by allowing soil biological communities to thrive. The microbial and fungal communities in the soil are necessary to break down crop residues and return them to the soil as organic matter. Dean Sponheim, a member from Floyd County, was able to notice this difference in his fields after he supplemented his reduced tillage with cover crops. “After incorporating cover crops, you can sit back and let the living organisms or ‘underground livestock’ do the work for you and improve your organic matter.” One of the upshots of higher organic matter and active soil microorganisms is higher aggregate stability in soils which gives it that all-important structure that creates and holds soil pores open even in the face of disturbances like heavy rain or being driven on by equipment. Dejong-Hughes explains this in her research as well, “Reducing tillage helps preserve the soil’s natural structure, making the soil more resistant to erosion and the negative effects of heavy field equipment.”

And Save!

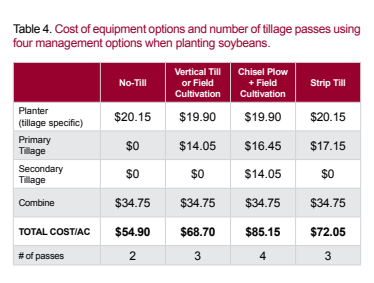

Cost of equipment options and number of tillage passes using four management options when planting soybeans

Among the advantages reduced tillage has on the soil health and field quality, there are additional benefits noticed by farmers. Reducing the amount of tillage means farmers and their equipment are in the field less. This saves money in multiple facets including; fuel, labor and equipment maintenance. The graph below breaks down the cost using four different management options. As displayed in the figure (right), no-till is the cheapest tillage option while chisel plow combined with field cultivation is the most expensive. You can save approximately $30 per acre! Not only are farmers saving money by eliminating passes of tillage, but stress during planting time is decreased by fewer mishaps with equipment.

Not only is stress decreased surrounding the planning and operation of field equipment, but there is also less physical stress on the body. The strain of extensive field operations shows up as aches and pains in farmers’ bodies. The US Center for Disease Control lists chronic exposure to vibrating equipment as one of the leading causes of musculoskeletal disorders among farm workers. The Great Plains Center for Agricultural Health within the University of Iowa College of Public Health recently published a study in the Annals of Work Exposure and Health that measured Whole-Body Vibration (WBV) levels experienced by 55 farmers using 112 machines in the course of their daily tasks. More than half, 63 machines, had sufficient vibrations to reach the European Union’s action level within eight hours of continuous use. They found tractors specifically had high levels of WBV because they rely on seat-based suspension systems that don’t mitigate the transfer of machine vibrations to the users’ feet, seat or back.

Some of the health symptoms of exposure to WBV include speech interference; muscle fatigue and cramping; disruption of balance and perception; increased heart rate and blood pressure; increased breathing rate; and low back pain and damage to the spine. Limiting time in the tractor seat by removing or decreasing passes of tillage can have a real impact on farmer health and associated costs of medicine, doctor visits and other therapy farmers might use to control the symptoms of WBV.

What’s the Hold-up?

Adapting your mindset is just as important as modifying your equipment. Dean believes that, for him, a lot of the shift was psychological. “It takes a while to convince yourself that your fields are going to be fine without the extra tillage.” He started strip-tilling in 1999 and continues to see the benefits today, but Dean explains that it takes patience and adaptability: “Not everything is going to go the way you have planned, but for me, it was about being patient and having options when things go awry that helped with my success.”

Curious about how tillage and cover crops interact? So are PFI Cooperators. Last year three PFI farmer-researchers compared crop yields and returns on investment of strip-till and no-till production of corn and soybeans following a cereal rye cover crop. Read the full report here.